Advertisement

Judge Told Jurors In Meningitis Outbreak Case To Be Unanimous — But Verdict Form Shows Division

In the trial of pharmacist Barry Cadden, federal jurors were instructed that all 12 of them had to agree — guilty or not guilty — before reaching a verdict.

Cadden was at the center of a deadly outbreak of fungal meningitis linked to contaminated steroid injections prepared by his company, the New England Compounding Center. At least 60 people died.

Although Cadden was found guilty in March of racketeering and mail fraud, the jury found him not guilty of the most serious charge: second-degree murder, which could have meant a life sentence.

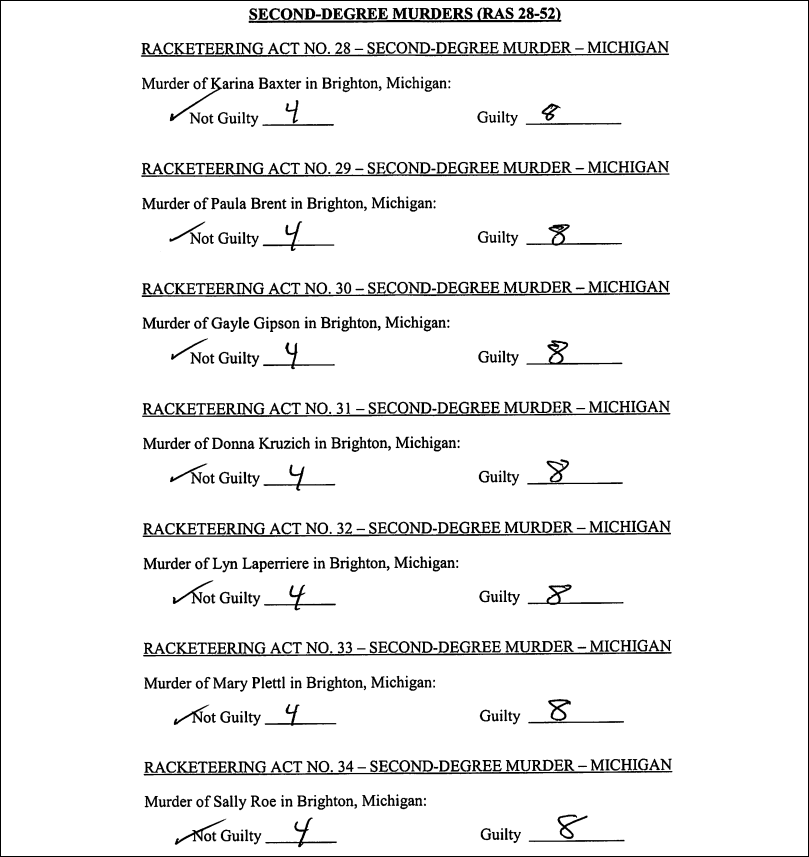

But the jurors' verdict form indicates they were not unanimous, as the court required, but divided. And the judge, U.S. District Judge Richard Stearns, who was the only one other than the jurors to see the verdict slips, did not question the jurors about their apparent division — which might have led to further deliberations.

Lawyers, former prosecutors and a retired federal judge are now calling the situation unprecedented.

'It’s An Extraordinary Verdict Form'

Cadden's trial lasted nine weeks, with juror deliberations going on for 20 hours.

"And then the verdict comes in," lawyer David Schumacher says, "and, of course, there’s incredible anticipation as the jury comes back and the verdict is about to be read. The courtroom was full. The overflow courtroom had lots of people in it. People were hanging on this verdict to see what was going to happen."

Until January, Schumacher was assistant U.S. attorney and deputy chief of the health care fraud unit which investigated and then prosecuted Barry Cadden.

"Just an incredible human tragedy," Schumacher says about the NECC outbreak, "with hundreds of people injured and numerous people dying as a result of these tainted steroids that were injected into people’s bodies."

Judge Stearns had given the jurors the standard instructions, he says.

"You have to be unanimous up or down: guilty or not guilty," Schumacher says.

Advertisement

The clerk handed the jurors' verdict form to Judge Stearns. He read the 21 pages of verdicts to himself. But there was something amiss.

Stearns said, "In some cases on the verdict slip ... the jurors indicate how they voted in terms of a division."

NYU School of Law Professor Stephen Gillers, considered a national expert on judicial ethics and the law governing trials, says that was "weird."

"The word 'division' is inconsistent with the word 'unanimous,' and verdicts have to be unanimous in federal court in criminal cases," Gillers says.

"It’s an extraordinary verdict form, it’s like nothing I’ve ever seen."

David Schumacher, former prosecutor

When Stearns told his clerk to read the verdicts but not how the jurors voted, two puzzled prosecutors looked at each other as if to say: “What?”

What they heard, at first, was reassuring — “guilty” verdicts for each of the first 27 racketeering acts.

In all, Cadden would be convicted on 57 counts of racketeering and mail fraud.

But the tide changed when it came to the acts of second-degree murder. They were at the heart of the case because convictions could mean Cadden would go to prison for life.

“Not guilty” verdicts were read for every one of the 25 second-degree murder acts.

The prosecutors and a packed audience were stunned.

Remember: The clerk was the only one with the verdict form, so the lawyers couldn't see what she was reading. But much later, when they did see that form and when it was too late to do anything about it, the prosecutors discovered something even more stunning.

"It’s an extraordinary verdict form, it’s like nothing I’ve ever seen," Schumacher says. "They actually recorded numbers. They're literally recording their votes."

On each verdict where the jurors checked “not guilty," you can see how they voted. Nine for guilty and three for not guilty on some of the murder charges — eight to four on others.

I asked former Boston federal Judge Nancy Gertner if she has ever seen numbers on a verdict form.

"No, never," Gertner said. "I’ve never seen a verdict form with numbers, absolutely."

“Are you kidding me?” said one trial lawyer. "No one ever enters numbers on a jury form.”

The lawyer was one of several who spoke to us but requested anonymity because he tries cases before Judge Stearns.

The Possibility Of A Hung Jury

"It is a gigantic mess," says Harvey Silverglate, a trial and appellate lawyer and a legal writer.

Silverglate points to all the signs that the jurors returned verdicts that weren’t unanimous and, thus, weren’t verdicts at all.

Whenever the form says "guilty," for instance, there is a check mark and a handwritten note: “check mark equals unanimous."

You don't see that for the "not guilty" verdicts, which are the only verdicts that come with numbers — numbers that show a split.

"To me, this means there was a hung jury," Silverglate says.

That is, a jury that was divided.

NYU's Gillers calls the situation “astonishing."

"It’s impossible, really, to say what the jury was thinking," Gillers says. "At best there's an ambiguity. My best guess is that the jury was telling the judge where it was divided on certain counts and where it was unanimous on other counts, and the judge misinterpreted that to mean that it was unanimous on all counts."

Gillers calls the ramifications of this ambiguity "enormous."

Because if the judge determines that jurors are split, he can send them back to resume deliberations — and the verdict form for Cadden shows the jurors were close to 12, for guilty, on a number of murder charges.

"The judge has the document in front of him. He sees the numbers. It was incumbent on the judge to recognize immediately that was not clear."

Stephen Gillers, NYU law professor

And if jurors still can’t reach a verdict, the judge can declare the jury is “hung” and then declare a mistrial.

A mistrial in this case would have allowed the government to retry Cadden on those particular charges where the jurors could not agree.

What happened instead when Judge Stearns accepted the jurors' “not guilty” verdicts meant that Cadden could not be retried on murder charges that could have sent him to prison for life.

That’s why that verdict form was so critical, says Silverglate.

"You look at it now and you say, 'How could the judge have not realized that this is, at the very least, ambiguous? How could he not have realized it?' "

"I know what would have happened in my courtroom if I saw these numbers," Gertner says. "I would have had a sidebar, that is to say a confidential discussion with the lawyers, and say, 'What do you want me to do with this?' "

Consulting the lawyers and questioning the jurors was the opposite of what Judge Stearns did when he told the clerk to read the verdicts and not the numbers.

"So the question is, what's the significance of these numbers?" Gertner says.

She says she would have solved the mystery by asking the jurors whether they were unanimous where the numbers indicated they were not. It would have taken 15 minutes.

Gertner does put some blame on the prosecutors. She says they should have inquired when the judge hinted at a problem, although other attorneys say that would have required near-clairvoyance.

And Silverglate blames the prosecution for confusing the jurors with complicated verdict forms that resulted from charges that were unnecessarily complex.

Yet Gillers keeps the judge at center stage. I asked him: Does the majority of the responsibility for what happened fall with the judge rather than the lawyers?

"Oh far and away with the judge," Gillers says. "The judge has the document in front of him. He sees the numbers. It was incumbent on the judge to recognize immediately that was not clear."

The Question That Was Never Asked

There was one last chance for the court to make sure the jurors understood that they needed to be 12 up or 12 down, either way, on every verdict.

Before the jury came in for the last time, Judge Stearns had told the court that “when the clerk finishes, I will ask each of the jurors to affirm that this, indeed, is your unanimous verdict.”

But the judge never did that. Instead, and after the last verdict was delivered, the clerk asked: “So say you, Mr. Foreman?”

"Yes," the foreman said.

"So say you, all members of the jury?"

"Yes."

If there was a question that would have confirmed that each juror had understood that all the verdicts had to be unanimous — and were indeed unanimous — that wasn’t it.

"With all due respect to the judge, he’s a bright guy," Silverglate says. "He must have seen the potential problem. He was trying to whitewash it. And as a result, he made a worse mess. He probably should have been much more frank with the lawyers as to what was in those juror slips."

By the time the lawyers got to see the verdict form, the jurors were already on their way home.

Only they know for sure what those numbers mean.

But nearly two months later, Judge Stearns has still not made the list of jurors public. The federal court in Boston has ruled that jury lists are presumed to be public. But Stearns' clerk told WBUR she is not sure if and when it will ever be released.

So, like Judge Stearns, we have not questioned the jurors.

The judge had no comment.

This segment aired on May 15, 2017.