Advertisement

3 Developers Expected To Bid For The State's First Offshore Wind Farm

It's a new era for renewable clean energy in Massachusetts. Utilities are asking developers to bid on a contract to build the state's first offshore wind farm. Competition is expected to be intense.

Last summer, state lawmakers committed Massachusetts to procure more offshore wind than any other state. Over the next decade, utilities here will have to buy 1,600 megawatts of electricity generated in waters off the coast. That's enough to power about a million homes, or about twice the electricity produced by the Pilgrim nuclear power plant, which will shut down in two years.

"It's a huge opportunity and I'm really excited to see what we get in our first procurement," says Judith Judson, commissioner of Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources.

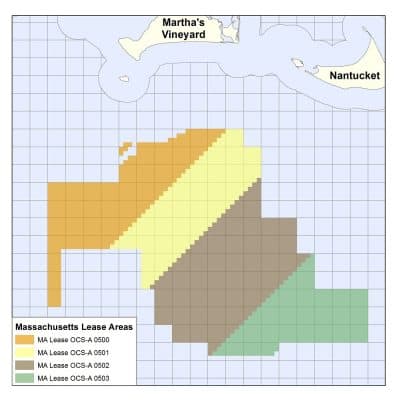

Some of the best wind in the world blows off the coast of Martha's Vineyard, where the first offshore farm is set to be built.

"We have tremendous potential for offshore wind," Judson says. "We're taking the first step and it has the potential to bring jobs, to bring industry, and grow our clean energy economy."

While Massachusetts' goal for offshore wind over the coming decade is ambitious, it pales in comparison to Europe, where offshore wind over the last 25 years has become a $100 billion industry.

Matthew Beaton, Massachusetts secretary of energy and environmental affairs, says the state is taking "a toe in the water approach."

"We'll see how this goes. We intentionally wanted to start off slowly because it's a new industry," he says. "It's seen great success in Europe, but we're going consciously — but fast enough — to see some of the real economic impacts we're here to promote today."

Three teams of developers are expected to submit bids to build the first offshore wind farm. They'll have to compete on price. The utilities want a guaranteed wholesale rate for electricity they buy for the next 20 years.

Advertisement

"We're really trying to make sure we get the electrons developed in the most cost effective way possible but also at the same time try to maximize the opportunities for local and regional companies to be part of that supply chain," Beaton says.

The big question is who will supply the services and parts to the fledgling offshore wind industry, says Peter Rothstein, president of the Northeast Clean Energy Council.

"The supply chain is going to be a multibillion-dollar industry here in Massachusetts in the next half dozen years," he says.

New York, New Jersey, Maryland and Delaware are also planning offshore wind farms.

"It's a very big deal. It's a very big deal. It's a great opportunity to scale new business," Rothstein says. "And if Massachusetts is one of the first hubs for this kind of activity then Massachusetts companies will have the expertise over the whole Eastern region of the U.S."

A local supply chain does not exist yet, so the first wind farm off the coast of Massachusetts will largely be built with parts from Europe. Those generators and blades are enormous and getting bigger. The biggest turbines in Europe, which now produce electricity that's cost competitive with fossil fuels, are taller than New England's highest building (formerly called Hancock Tower).

The cost of getting the machines here will be very expensive.

Jeff Grybowski, head of Deepwater Wind, one of the companies competing for the Massachusetts offshore contract, says that a homegrown supply chain makes sense in the long run.

"We're at the beginning of an industry that I think will be built out over decades and decades and that's a good thing because what we'd like to do as an industry is to build a few projects up and down the coast, every two years," Grybowski says. "So we're talking about an industry that will sustain jobs for decades."

The promise of sustainable jobs, a sustainable industry and sustainable energy — a triple bottom line now in the works off, and on the coast, of Massachusetts.

"This competition that's happening in Massachusetts is really a key to what happens in the U.S. and that will be a watershed moment for our industry," Grybowski says.

The winning bid will be announced next summer, with the first steel in the water a year or two later.

This segment aired on June 30, 2017.