Advertisement

Losing to Lyme

Science Shortfall: Why Don't We Know How Best To Fight Ticks And Lyme Disease?

Part of our Losing to Lyme series

Beneath the midsummer Martha’s Vineyard sun, the gentle wind breathes waves of motion into a flag-sized swath of white fabric laid out on a large rock. Suddenly, an eye-catching bit of motion: a black, eight-legged speck on the move. Tick scientist Sam Telford pounces. He snatches it with his tweezers and tucks it into a small plastic vial with a satisfying pop.

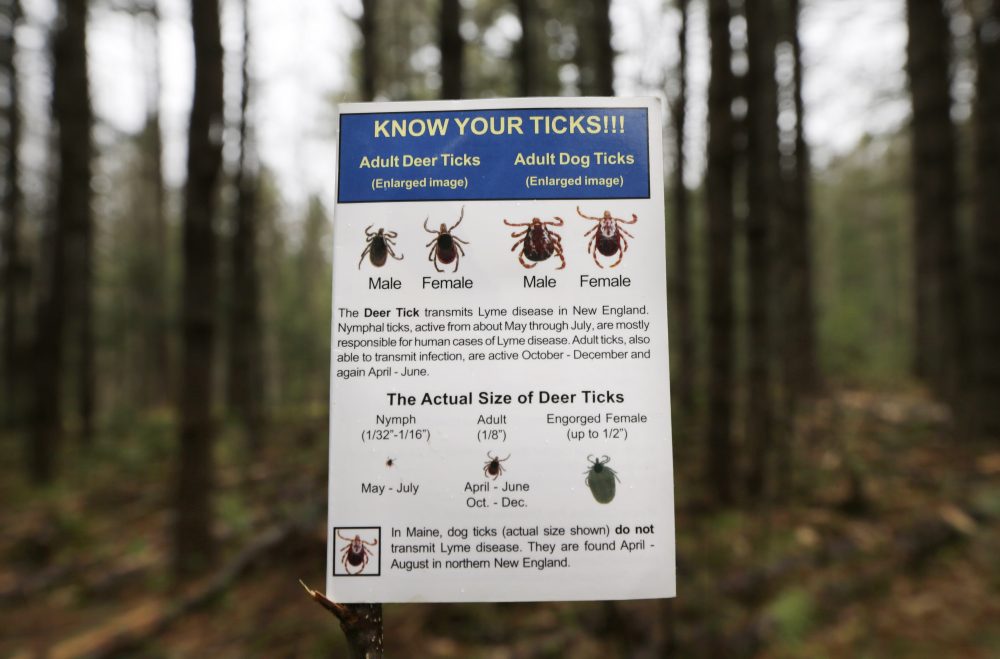

There, the deer tick, endemic carrier of Lyme disease and other infections, lands in a comfy habitat of green leaves Telford has prepared for it. “I need these ticks to stay alive,” he says.

Telford will gather dozens of them in the course of a Chilmark morning, as part of research that has brought him tick-hunting to Martha’s Vineyard so many times that he’s lost count. For 30 years, Telford, a professor and epidemiologist at Tufts University’s Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine, has been working to understand ticks and the diseases they spread to humans.

These years have brought some progress: We have widely accepted practices for personal tick-bite protection, from repellents to body checks. But the biggest and most important question remains unanswered: How do we stop the spread of Lyme?

“What have we done for Lyme disease?” Telford asks. “The incidence keeps increasing and increasing, the distribution keeps increasing and increasing.”

Good Science Is Hard To Do

Take, for example, deer control. One of Telford’s first projects, back in the 1980s, looked at what happened to tick numbers when the deer population on Great Island in south Cape Cod was reduced.

The $20,000-per-year study showed that cutting the number of deer worked to cut the number of ticks, which depend on sucking deer blood during their life cycle. But it lacked definitive proof that the drop in ticks also brought a drop in Lyme disease, because the modest funding did not cover a study big enough to draw a clear conclusion.

Deer studies like Telford’s illustrate a central problem with Lyme and tick-borne disease prevention: We don’t know the most effective recipe to reduce tick populations and prevent Lyme because the studies that would definitively answer questions like that have not been done. Should your town follow Telford’s advice and cull deer populations? Spray public spaces? Trim back trails? Do all of the above?

The problem is complex, too complex for a simple answer.

“For a very long time, people have been looking for that silver bullet or the magic answer to make Lyme disease go away,” says Catherine Brown, the state's public health veterinarian. “We’ve known for a while now that’s just not going to happen.”

Advertisement

“For a very long time, people have been looking for that silver bullet or the magic answer to make Lyme disease go away. We’ve known for a while now that’s just not going to happen.”

Catherine Brown, the state's public health veterinarian

Put another way, trying to fight Lyme is like “trying to solve a multivariate equation with 18 variables and only knowing two of them,” says Henry Lind, the co-chair of the Barnstable County Lyme/Tick-Borne Diseases Task Force.

Ideally, when scientists do a study, they control all important factors, then change just one or two and observe the impact. But in an environment as complex as what surrounds tick-borne diseases, many factors affect the ecosystem.

We know deer, white-footed mouse and chipmunk populations are important in the tick life cycle. We know if they have a lot of food one year, they have more babies. We know ticks like warm, humid areas like leafy underbrush, and thrive in warm, wet summers but their numbers dwindle in drought.

Then there’s what humans do -- whether we wear personal protection, put on repellent, spray our lawns, treat our pets, check our bodies for ticks. And while we can control our own behavior, we can’t control the whole ecosystem, especially the weather and food supply for rodents.

Finally, we can’t just count the number of ticks at the end of a study because what we really care about is the number of human infections. Some studies show impressive reductions in the numbers of ticks, but don’t show much impact on the number of infections.

In the face of this complexity, scientists have to do high-quality studies to give more certainty to the results. But that means large studies that span years and large areas to be more sure the results aren’t just due to weather changes or other things outside our control. All of that costs a lot of money.

Take, for example, a recent high-quality study led by Alison Hinckley, a CDC scientist. The researchers sprayed yards once a year with tick-killing chemicals and looked for the effect on tick bites and infections.

It was a two-year, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. It’s tough to get higher quality than that. It looked at over 2,700 households in three states. And it went further than most studies by looking not just at the numbers of ticks but also the number of tick-borne infections.

All of this cost about $3 million, a huge sum in the world of entomology and ecology.

And it didn’t work. That is, tick numbers dropped by 63 percent but tick sightings and infections didn’t change. Maybe people got ticks from the areas of their yards that weren’t sprayed, like gardens. Or maybe they got infected while on hikes. And, since it was only a two-year study, maybe rainy spring weather made spraying less effective.

An editorial in the same journal, headlined in part “Still No Silver Bullet,” lamented: “Unfortunately, this study confirms that effective prevention of tick-borne disease remains arduous and will likely rely on multiple methods.”

But the study wasn’t a waste. It answered an important question and offers opportunities for digging deeper in the next study.

Richard Ostfeld, a senior scientist at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, wants to do that next-step research. He and his co-director, Felicia Keesing of Bard College, have been encouraged by a recent trend toward “integrated tick management” that includes multiple ways to reduce tick populations, then checking the impact on rates of Lyme disease.

Their randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study will look at the effect of two interventions: a sprayed fungus that kills ticks, and bait boxes that drop a tiny amount of tick poison on small mammals. Because ticks don't respect property boundaries, the study examines whole neighborhoods instead of just treating single yards.

It will track four groups of neighborhoods:

- Where yards are sprayed with the tick-killing fungus

- Where bait boxes with the tick-poison are installed

- Where both are done

- “Control” neighborhoods that get placebos (water spray and/or bait boxes with no tick poison)

The researchers will then compare the tick encounters and infections of each group. The goal, as the study puts it, is to “answer once and for all whether we can prevent cases of tick-borne disease by treating the areas around people's homes.”

Follow The (Lack Of) Money

Thus far, Ostfeld and Keesing's five-year study, called the Tick Project, has raised only $5.5 million of the $8.8 million it needs — 90 percent of it from the Cohen Foundation, and the rest from various donors and state and federal sources.

Such high-quality studies do not come cheap. “Those studies are very difficult and expensive to do,” says Dr. Ben Beard, chief of the bacterial disease branch in the CDC’s Division of Vector-Borne Diseases. An additional challenge: Funding is often allocated for specific diseases, he says, but the problem is broader — tick-borne diseases in general.

From 2006 to 2010, about $370 million in federal research money went to tick-borne diseases, according to an Institute of Medicine report, with over half of it spent on tularemia, an uncommon disease but cause for concern because of its potential use in bioterrorism. Funding dropped off dramatically as concern about bioterrorism waned.

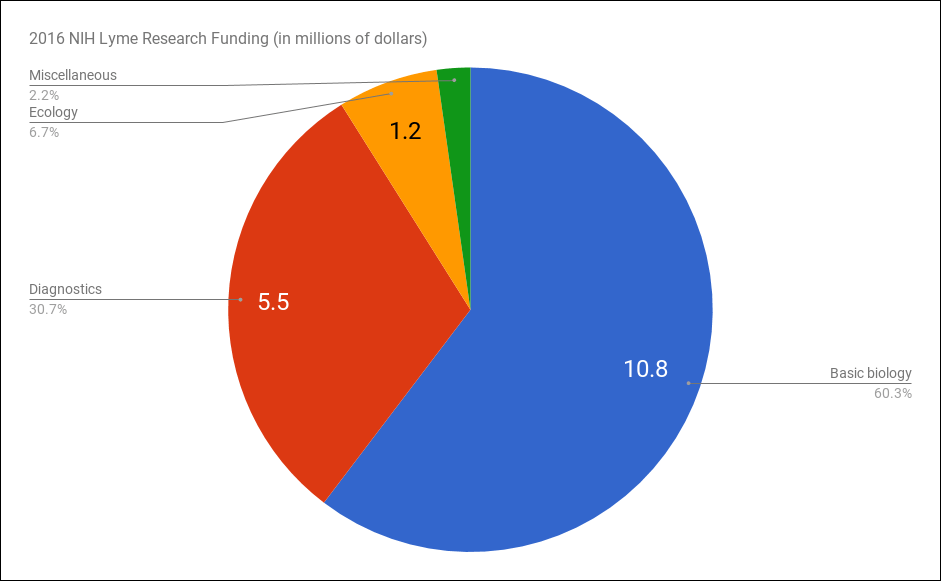

Most money spent on Lyme goes to basic biology research, relatively little to research trying to understand the best tick reduction and prevention strategies. Today, according to an analysis of the NIH grant database, almost two-thirds of 2016 research funds for Lyme disease went to study basic biology. Another third went to studies looking for better diagnostics. Research of the kind done by Ostfeld and Telford was less than 10 percent of the 2016 total: only about $1.2 million.

Even in a state like Massachusetts, where Lyme is so widespread, state funding for research is highly unlikely. “State government quite frankly doesn’t have the money to be funding medical research,” says Rep. David Linsky of Natick, who chaired a legislative commission on Lyme. “I’d like to see the federal government that is really the source of funding for extensive research put some more money into Lyme disease.”

And funding is always tight for ecologists who study ticks and the animals they crawl on. For example, Telford doesn’t have research funding that supports his tick-gathering trips to the Vineyard. Like virtually every scientist, he’s had grants denied, including his most recent proposal to try to bring back Lymerix, the Lyme disease vaccine that was pulled from the market in 2002.

The limited funding means the science on preventing ticks is filled with smaller studies, many without controls, with small sample sizes, small geographic areas, that don't look at the impact on human infections.

The result is a plethora of studies with confusing results, like the deer studies: Some, like Telford’s, show deer reduction works. Others seem to show it doesn’t work as well. None of the studies have conclusively linked deer reduction to effects on human cases of Lyme disease.

Scientists simply don’t have the funds to do enough high-quality studies. As Ostfeld says, “the obstacle is more financial, not intellectual.”

Falling Between The Funding Cracks

Research on preventing Lyme also falls between the cracks in scientific funding. The National Institutes of Health fund research on better diagnosis and treatment of human disease, so they are not likely to fund field ecology research, even for Lyme disease, Ostfeld says.

The National Science Foundation funds ecology research, but its budget is much smaller than the NIH budget. An $8 million study could be as much as 10 percent of their ecology budget in any given year. And they do not tend to focus on public health.

The CDC would be a logical funding source, but it does not have a large external research program in this area. CDC researchers are helping with Ostfeld’s study, he says, but there’s “no way in the world they could fund an $8 million, five-year project."

“We always have a wish list of unfunded studies, but there are a lot of competing disease issues,” Dr. Beard of the CDC says. Some recently announced funding for "vector-borne diseases" may help.

To sum it all up: “With over 300,000 new cases each year, the scope of the problem definitely hasn’t been addressed by the scale of the funding,” says Dr. Tom Mather of the University of Rhode Island. “I’m not sure when and if we can change that -- maybe when there are 500,000 new cases of Lyme every year. Or maybe when ticks fly.”

And things look likely to get worse before they get better. Dr. Beard said in a presentation last year that he sees a troubling trend of less money going into tick-borne disease and not enough scientists specializing in it. “It’s not the disease outbreak du jour that gets the attention of the media,” he says.

So, no magic bullet. Little money. No simple answer to a number of questions about what communities should do. But Telford of Tufts, perseveres — still pushing for deer reduction, among other anti-tick tactics, and still arguing that communities and neighborhoods need to join forces to address the problem together.

He keeps his lab afloat from a hodgepodge of sources — a small grant here, some funds from collaborations there — and with the help of his wife, Heidi Goethert, also a trained scientist, who works in the lab full-time but only gets paid half-time to stretch the money as far as possible.

In early June, he submitted another National Institutes of Health grant to study a Powassan-like tick-borne virus, but it will be months before he hears the results.

“I remain hopeful,” Telford says. “I remain also very guarded in my optimism.”

David Scales MD, Ph.D., is a physician at Cambridge Health Alliance and Harvard Medical School. He can be found on Twitter @davidascales. The Morning Edition audio report atop this post was done by CommonHealth editor Carey Goldberg.

This segment aired on July 18, 2017.