Advertisement

BU Researchers: Hernandez's Brain Reveals Most Extensive Evidence Of CTE They've Seen In A Person So Young

Resume

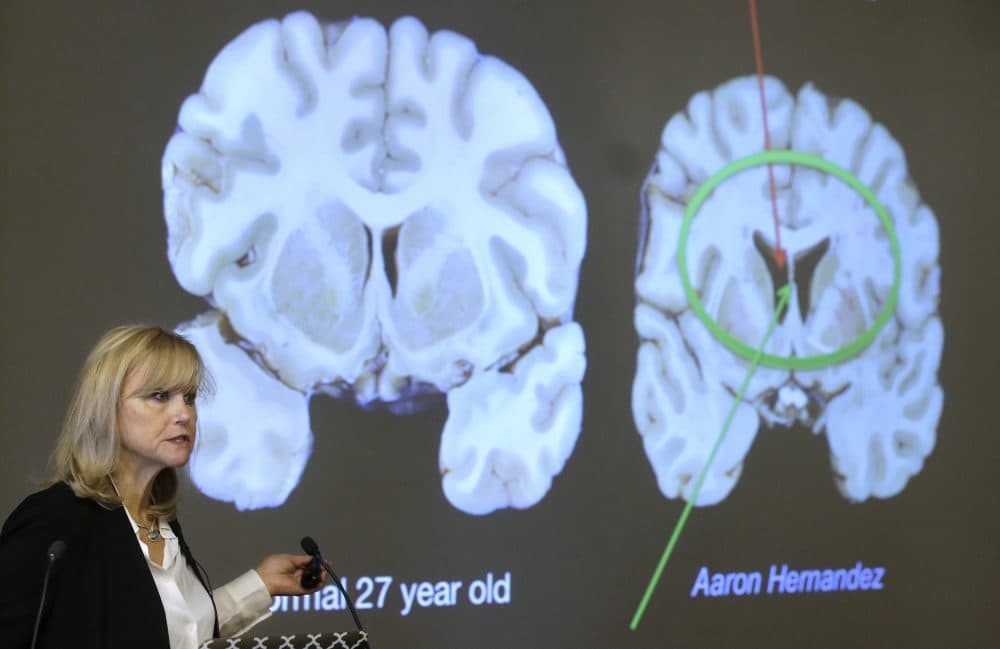

Boston University researchers say the donated brain of former New England Patriots player Aaron Hernandez reveals the most extensive evidence of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) they've ever seen in a person that young.

Hernandez's family donated his brain to BU's CTE Center after his April suicide. The 27-year-old hanged himself in his prison cell while serving a life sentence for one murder, and days after being found not guilty of two more.

The BU researchers say that Hernandez's brain has been one of the most significant contributions to their investigation of CTE, a degenerative brain disease found in people with a history of repetitive head trauma, and which can currently be diagnosed only during an autopsy.

"We very rarely get an opportunity to see disease in such a young person," said Ann McKee, director of BU's CTE Center.

BU holds more than 400 brains donated by athletes and others. Even so, McKee said, Hernandez's brain stands out.

"We've never seen this in our 468 brains, except in individuals some 20 years older," she said.

McKee says the medical examiner delivered the brain in pristine condition. She showed slides of it Thursday at a conference at BU showing extensive damage in different regions.

"All of these caused by repetitive brain trauma," she said.

The BU researchers believe CTE is caused by hits to the head. McKee showed evidence of older injuries to Hernandez's brain consistent with such impacts.

"We also saw evidence of previous micro-hemorrhage, or micro-bleeds, something that we associated with head impacts and concussive injury," she said.

She added that Hernandez's brain damage is consistent with the behavior of someone who acts impulsively.

"While I'll not connect the dots with his behavior or difficulties during life, I'll make these points: The frontal lobes — and his frontal lobes were very severely affected — are involved in problem-solving, judgment, impulse control and social behavior," she said. "The amygdala, which was affected in Aaron Hernandez as well, is involved in emotional regulation, emotional behavior, fear and anxiety."

A conference attendee asked McKee whether helmets could be designed to prevent head injuries that could lead to CTE.

"This acceleration-deceleration rotational injury happens despite the helmet," McKee said. "It happens inside the skull. It's an intrinsic component of football. Every time you'll have a tackle or a collision, you're going to have these rapid forces that are affecting the brain."

Preventing sub-concussive hits is what we need to focus on in football, McKee says, and helmets do not prevent those.

The Patriots declined to comment.

The BU researchers are looking for ways to identify the disease in living people.

This segment aired on November 9, 2017.