Advertisement

Analysis

How The Mass. Legislature Can Get Closer To Gender Balance

State Sen. Harriette Chandler, a Democrat from Worcester, became the acting president of the Massachusetts Senate this week, the second woman of the last three leaders to hold the gavel. Four of the state's six key constitutional officers are women, and one of our U.S. senators.

In the state Legislature, however, Massachusetts is very far from gender balance, and making no progress. Women make up a slim majority of Massachusetts residents, but only a quarter of state legislators.

The problem isn’t that women aren’t winning elections, but that they have too few opportunities to run. To move toward gender balance, women candidates will have to broaden the field. That means more women candidates challenging sitting lawmakers in party primaries and general elections, rather than waiting for open seats.

Progress toward gender parity in the state Legislature has stalled. From 1970 to 2002, women made remarkable gains, from less than 3 percent of lawmakers to 26 percent in 2002. Since then, the line has been basically flat. There are no more women in the Legislature today than there were in 2002.

When women run for the Legislature, they have a good track record of winning. Our own analysis shows that since 1980, women have won 73 percent of major party primaries they have entered, as well as 71 percent of the general elections that included at least one female candidate.

If the composition of the state Legislature continues the paltry rate of change we’ve seen since 1980, we’ll reach gender parity in the year 2072.

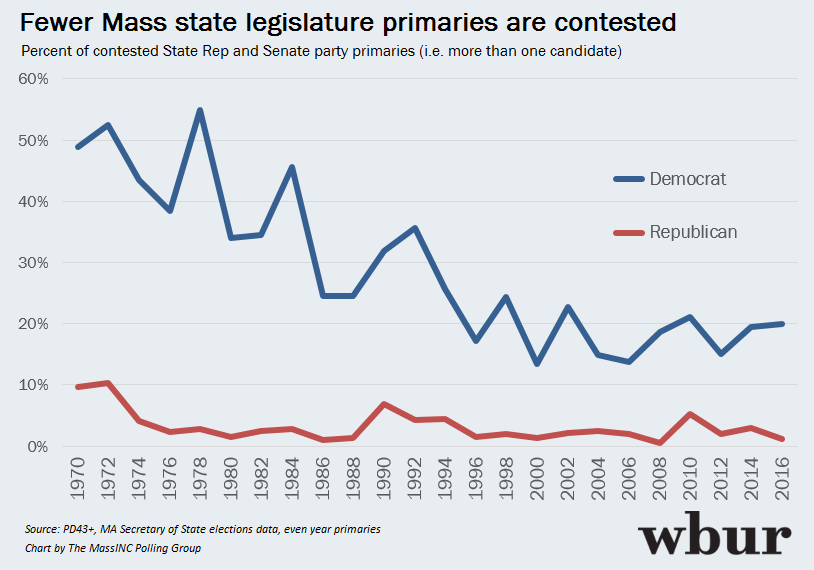

The bigger problems are too few open seats and an environment hostile to party primaries. Massachusetts has one of the lowest turnover rates of any state legislature in the nation. This contributes to the state’s dubious distinction of having the least competitive legislative elections in the country.

Thirty House members have been in office longer than their youngest voters have been alive; 20 have been serving since before their youngest colleague was born. Tenure is shorter on the Senate side, but 61 percent of current senators are themselves former state representatives. And every representative turned senator hanging around for decades means fewer opportunities to change Beacon Hill demographics.

Since 2010, retirements, scandals, new jobs and deaths have created an average of about 14 vacancies per year, out of 200 House and Senate seats. About a quarter of the vacancies over this period were women leaving their seats. That’s the same rate at which women who run in contested primaries go on to become legislators.

This has led to a sort of equilibrium, where women are entering and leaving the Legislature at a roughly equal rate. Individual women run and win every cycle, but the total number in the State House remains the same. To change this, female candidates will have to challenge sitting members, even if it means running against a fellow partisan in a primary election.

That’s a steep hill to climb in a state where it’s viewed as impolite or impertinent to run against an incumbent unless they are mired in controversy. And even then, as now-Congressman Seth Moulton showed in challenging the scandal-plagued John Tierney, it’s not always a popular thing to do. Women (and men) who want to run are told to wait their turns.

This don’t-rock-the-boat culture of elections in Massachusetts needs to change if there is to be gender parity in the Legislature. Parties can’t frown on primaries and hope to close the Legislature gender gap anytime soon. The two are in contradiction to one another. If the composition of the state Legislature continues the paltry rate of change we’ve seen since 1980, we’ll reach gender parity in the year 2072. Women need to be encouraged to run, yes for open seats, but also in primaries — against other Democrats. Against other Republicans.

We do that less and less these days in Massachusetts.

It's true that incumbent re-election rates are very high in Massachusetts. When incumbents run, they almost always win. But this is a bit misleading since they often run unopposed. Only about 1 in 10 incumbents face party primaries, according to a CommonWealth magazine analysis. More face general election competition, but most districts in Massachusetts aren't very competitive across party lines. In mostly partisan districts, the primary is often the only real chance at competition. It's hard to say what the impact would be of a burst of primary challenges, particularly given the charged political year we are entering in 2018.

To get past simple replacement rate outcomes, Massachusetts also needs more women candidates. There are organizations working on this and some early local signs of success: Boston voters this year elected a City Council where six of 13 members will be women of color, a better reflection of the city's demographics. And early data at the congressional level shows a burst of women candidates for the year ahead, with a fourfold increase in the number of women challenging incumbents.

Our Massachusetts democracy is, frankly, a bit tired, and needs a shot of vitality. Working toward proportional representation seems a self-evidently just way to shake things up.

Steve Koczela is president of MassINC Polling Group and a regular contributor to WBUR. He tweets @skoczela. Jake Rubinstein is a research associate at MassINC Polling Group and he tweets @jlrube.