Advertisement

'People Really Want To Live': Samaritans Volunteers Guide Callers, Texters Through Darkest Moments

They're known as "befrienders."

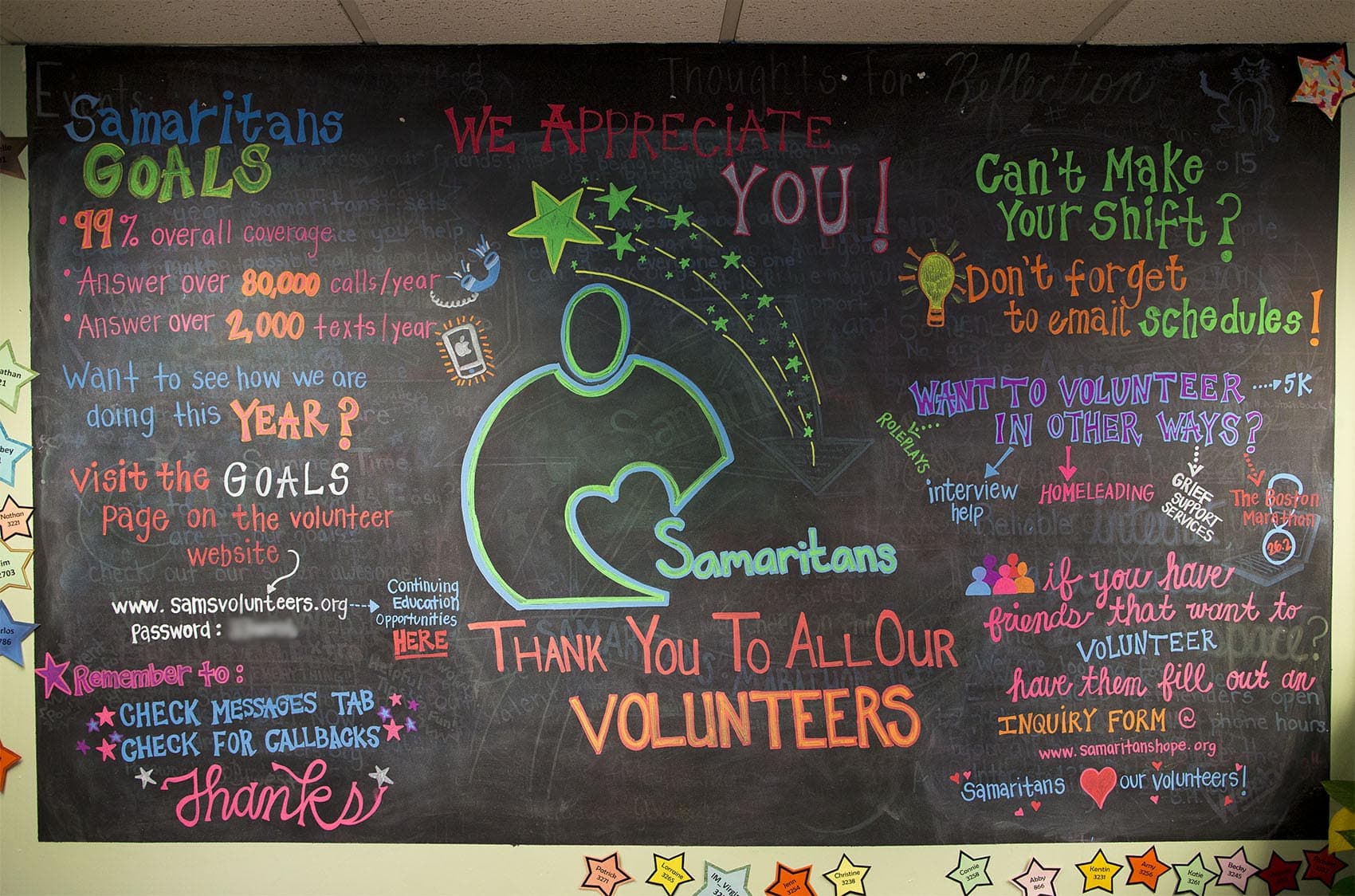

For four hours at a time, the Samaritans volunteers sit in one of 13 cubicles in a small office in downtown Boston, answering phone calls and texts from people who are depressed, lonely and sometimes considering suicide.

The volunteers' job is to be a friend — even if just for 10 or 15 minutes — to the stranger on the other end of the phone line.

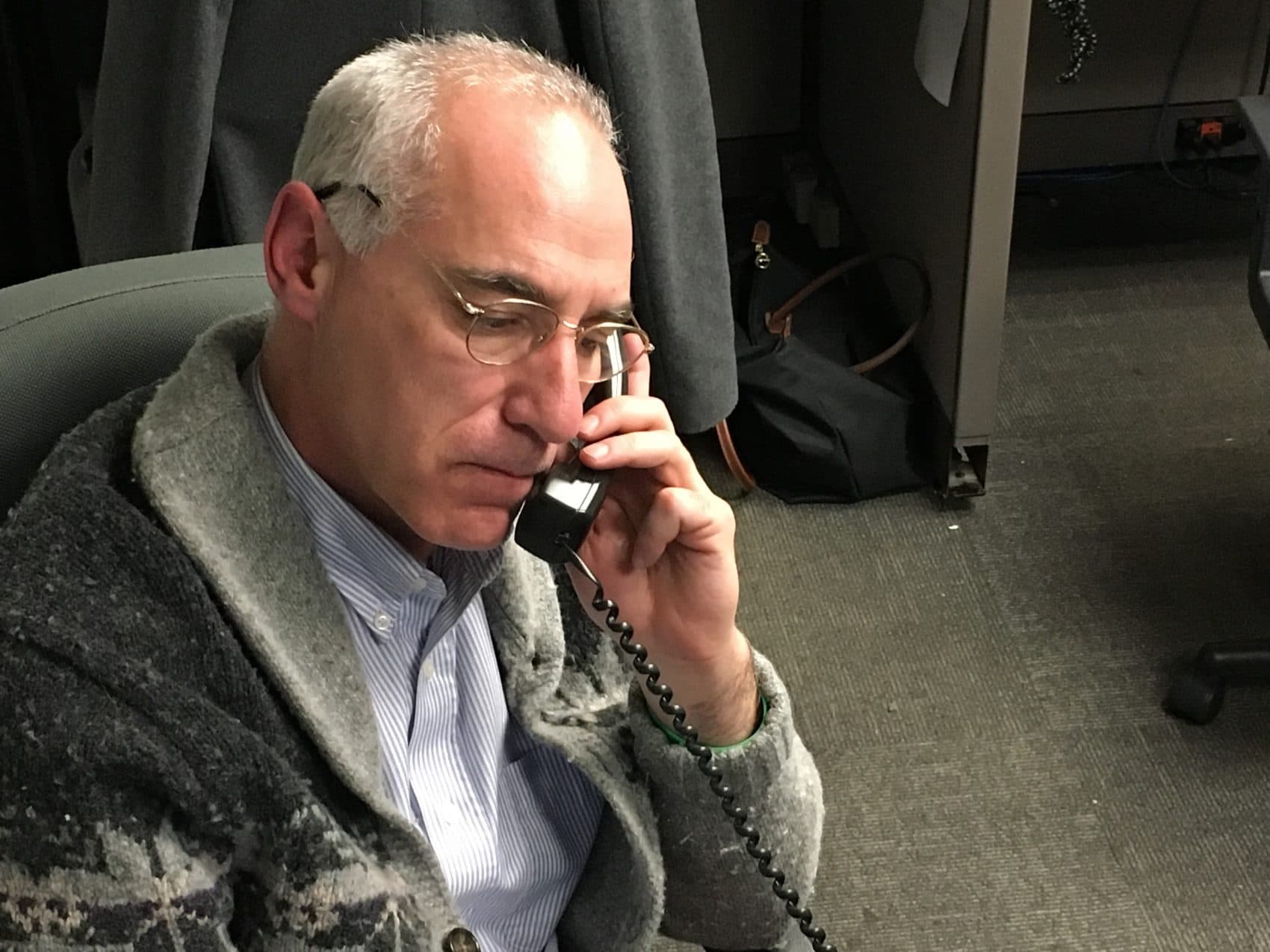

"So what's it like to live with depression every day for 35 years?" one of the volunteers, Brett, asks a caller. "Oh, wow. So you feel it as a kind of pain. Oh... my heart goes out to you."

We agreed to not use the volunteers' last names, so they can maintain their anonymity on the hotline.

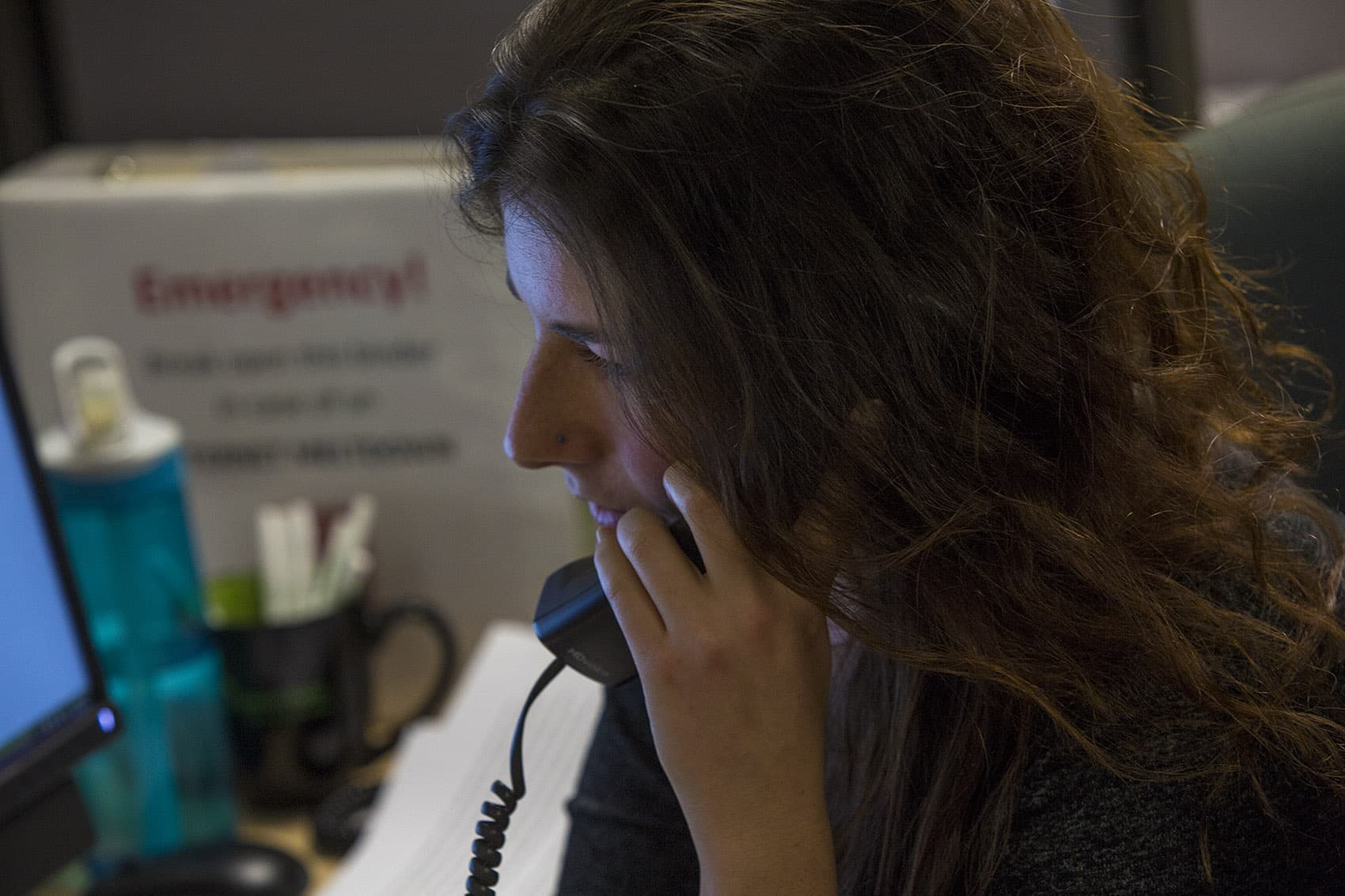

On another day, we meet 28-year-old Emma, who's been volunteering at the Samaritans hotline for almost three years. One of the 11 callers she talks with during the shift is a man who says he's having trouble appreciating the people in his life.

"It sounds like you've lost interest in everything that you used to enjoy," Emma says to the caller. "It sounds really lonely. That's a lonely place to be in."

The volunteers spend a lot more time listening than talking. That's one of the skills they learn in more than 40 hours of training. And they don't try to solve a person's problems.

"Our model of engaging with callers is not one that incorporates advice," Emma explains. "It's hard to just listen to somebody in pain and not offer anything tangible to kind of change that. I think what's helped me is to realize that what I'm offering is something that is so often not there in everyday life, which is the focus being on them and their struggles and their pain, and not turning it back on me ... to just sit back and give them something that's pretty rare, which is just a listening ear."

Advertisement

Brett, who's been volunteering for Samaritans since 2014, says that kind of listening requires being comfortable with silence in order to allow the caller time to formulate his or her thoughts.

"If you have somebody who's depressed, things are really moving slowly for them and it may be hard for them to converse with people in their daily life who are just so much quicker and don't have the patience for them," he says.

The Rare Kind Of Call

Brett takes five calls and has one long text conversation during this Monday evening shift. One of the calls starts off anything but slow.

The young woman on the other end is frantic — crying and screaming, Brett later explains. He tells her to take her time.

This is one of the rare calls: an acutely suicidal person. Each Samaritans volunteer answers just a couple calls like this per year, on average.

"OK, um, you took four Benadryl and Xanax?" Brett asks the caller.

He asks another volunteer to call the home leader — that's a senior volunteer who's on call and is consulted about anyone who appears to be at imminent risk. Then Brett continues talking with the woman on the phone.

"But you were trying to take your life? OK, so how are you feeling now?" he asks. "Yeah, well ... it's definitely a scary thing. So why don't we slow down and talk a little bit?"

The caller pretty quickly calms down. Brett asks her what led her to attempt suicide. He learns she's worried about reliving some painful memories when she travels over the holidays.

Her struggles run deep; she's attempted suicide before. Brett tells her he's worried about her.

"Are you still thinking about taking your life now?" She indicates she is not.

"OK, that's good to know," Brett responds. "Do you still have the pills out? Do you think you could put them away for now ... put them in a medicine cabinet or in your luggage or just somewhere where they're not immediately out there? It's kind of scary to talk to you while they're out. You put them in your bag? OK, thank you so much."

On the advice of the home leader, Brett encourages the woman to call Poison Control to tell them what she took. He asks her if another Samaritans volunteer can call back to check on her, an important step in suicide prevention. She says yes.

"She was really scared. I think what she had done was she'd really scared herself," Brett says after finishing the 14-and-a-half minute conversation with the woman.

And though he was calm, Brett says the call was stressful for him. The 51-year-old, who works as a dean at a university by day, says it helped to have the home leader making suggestions.

'Steering Towards The Pain'

One thing Brett did not do is try to convince the caller things would get better.

"We're not here to be cheerleaders. We're not here to say, you know, pull yourself up by your bootstraps," says Ruth Woods Dunham, director of crisis services at Samaritans. "One of the things that we teach in our training is what's called steering towards the pain. So we're helping to sort of guide that person along to talk about their their emotions, to talk about the fear and despair."

Though they can't offer solutions, the volunteers can guide a person to talk through possible steps he or she might take if something awful happens — like losing a home or job.

"What makes you concerned that you might be fired?" Emma asks a woman who's called the hotline, worried her employer is going to terminate her. "Absolutely, being fired is very disruptive and devastating," Emma says. Then, after listening to the woman explain further, Emma responds, "It sounds like you wouldn't really know where to turn if you did in fact lose your job."

It's about validating, not avoiding, the tough stuff. And that means volunteers ask every person who calls or texts the hotline if he or she is feeling suicidal.

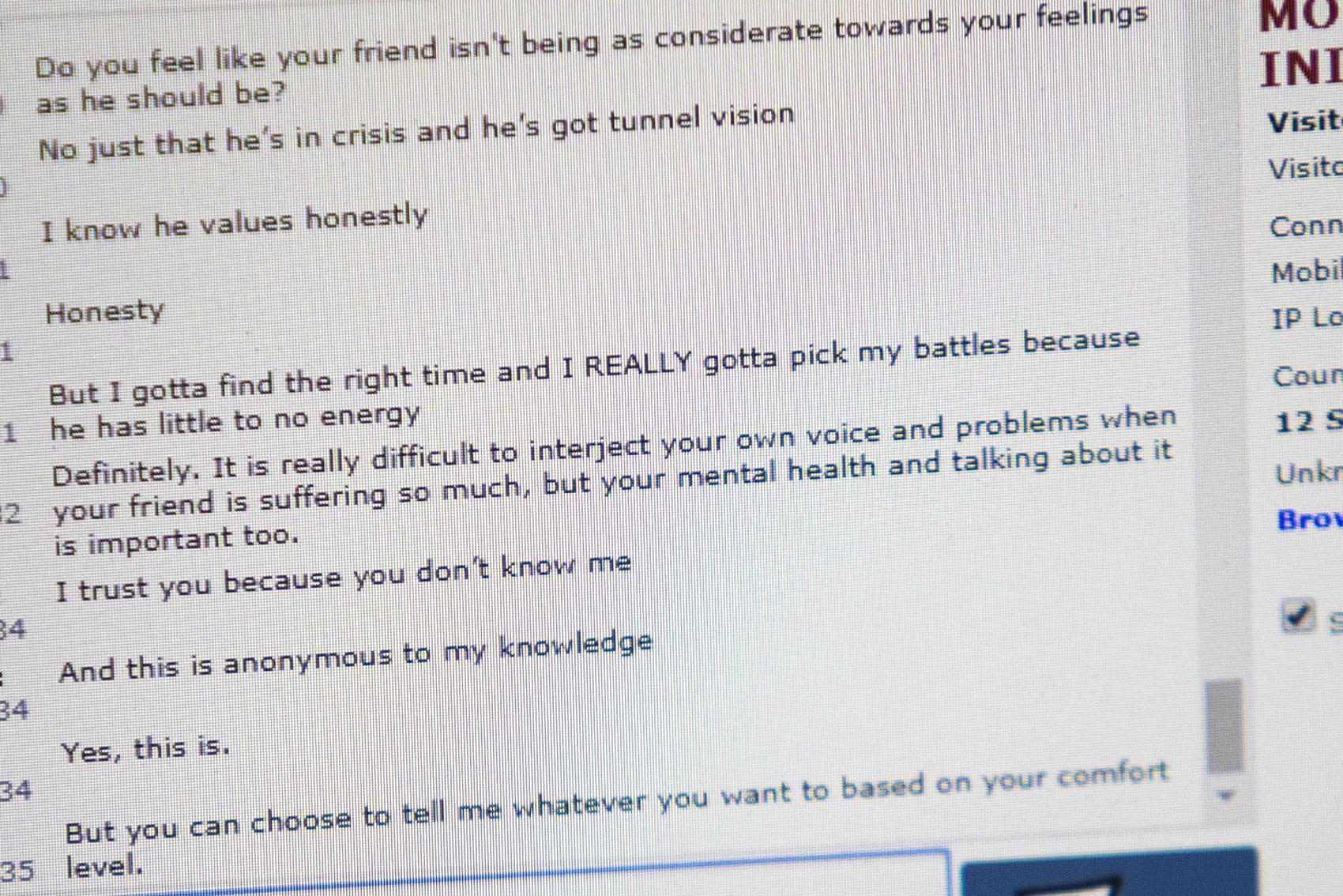

Texting For Help

Samaritans started the texting feature in 2015. Now, 7 percent of the 80,000 or so contacts the hotline answers in a year are text messages, according to Samaritans Executive Director Steve Mongeau. The text messages come in through the call center's computers.

Samaritans says the texting feature has brought in more young people in crisis who would not want to call and speak in person. In fiscal 2016, the hotline answered 1,703 text messages and 74,890 phone calls. In fiscal 2017 the number of texts jumped to 4,461. In the current fiscal year, Samaritans is on track to exceed 6,000 text conversations, with phone calls staying around the 75,000 mark. Phone calls come in from both the Boston hotline number and the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.

If volunteers determine someone who has called or texted is at imminent risk of suicide, they'll try helping the person come up with a plan to stay safe — including pinpointing people the person can turn to, such as a friend or therapist, and things he or she can do to temporarily divert attention from the situation.

If that isn't a good option, they'll ask if the person is OK with Samaritans calling emergency services. On the rare occasion someone doesn't say yes and the situation appears to be one of life and death, Samaritans says it calls emergency services without the person's consent.

Loneliness A Driving Force For Frequent Callers

Some callers call the hotline once. Others, including some senior citizens, call frequently, up to seven to nine times a day, according to volunteers. Many of them are lonely.

Samaritans recently implemented a policy limiting frequent callers who aren't suicidal to one or two calls per day, because, the organization's directors say, even 165 active volunteers working at least one four-hour shift per week aren't enough to answer all the calls coming in.

"As much as we'd like to have the resources and the people to speak to anybody for however long they need, we just don't," Emma, the volunteer, explains. "And so in order to make sure that we are available to everyone who's calling, we wanted to make sure it wasn't the same people who are monopolizing the phone lines."

They are able to speak with with 80 to 85 percent of callers, Mongeau says (up from approximately 70 percent in fiscal 2015). That means they miss 15 to 20 percent. Those people hear a message suggesting they call back.

'A Natural Tendency To Want To Live'

Emma says talking to people who contact the crisis line has made her more empathetic and a better listener in her daily life. It's so energizing, she says, it helped spark her decision to get a master's degree in social work.

"It's kind of that dance of the back and forth of really connecting with somebody and knowing that that's kind of impacted both of us, even though, you know, in different ways and on different levels, and even only in this brief moment," she says.

Brett has come to a powerful realization in talking with people who are suicidal.

"People really want to live. People don't want to take their lives. ... There is a natural tendency to want to live," he reflects. "So if someone is thinking of taking their life, they're feeling something that's so intense that it's probably isolating. Isolation sucks. Loneliness, isolation, they're just brutal. And, you know, we all want the same thing."

That thing is human connection.

On this end of the line, though, for the volunteer, the connection comes with a lot of unknowing. Will that person they just spoke with be OK tomorrow or next week?

"I do think everyone here develops a sort of tolerance for ambiguity," Brett explains. "You don't control the call, you don't control who calls, you don't control the outcome. And partially what you want to do is empower them and give them their life. So, while that's really stressful, you also know that it's their life."

If the volunteers need any proof they're making a difference, they need not look any further than one of the walls in their little office.

Tacked up on the wall are cards and letters, sent to the volunteers by people who've used the hotline.

One person writes, "Thank you so much for being there for me all these years, decades even, through some of my darkest hours."

Someone else writes that the call takers are the ground under his feet.

From another man, to the suicide hotline volunteers: "You are always the bright light shining forever in my life."

You can call or text Samaritans 24/7 at 877-870-HOPE (4673). The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 800-273-8255.

This segment aired on December 21, 2017.