Advertisement

For One Springfield Woman, A Complicated Desire To Preserve Racist Emblems

Monuments to the Confederacy have become sites of renewed controversy in recent months. But not all acts of confrontation and reconciliation occur in public.

In Springfield, Massachusetts, an African-American woman quietly brought Aunt Jemima into her home.

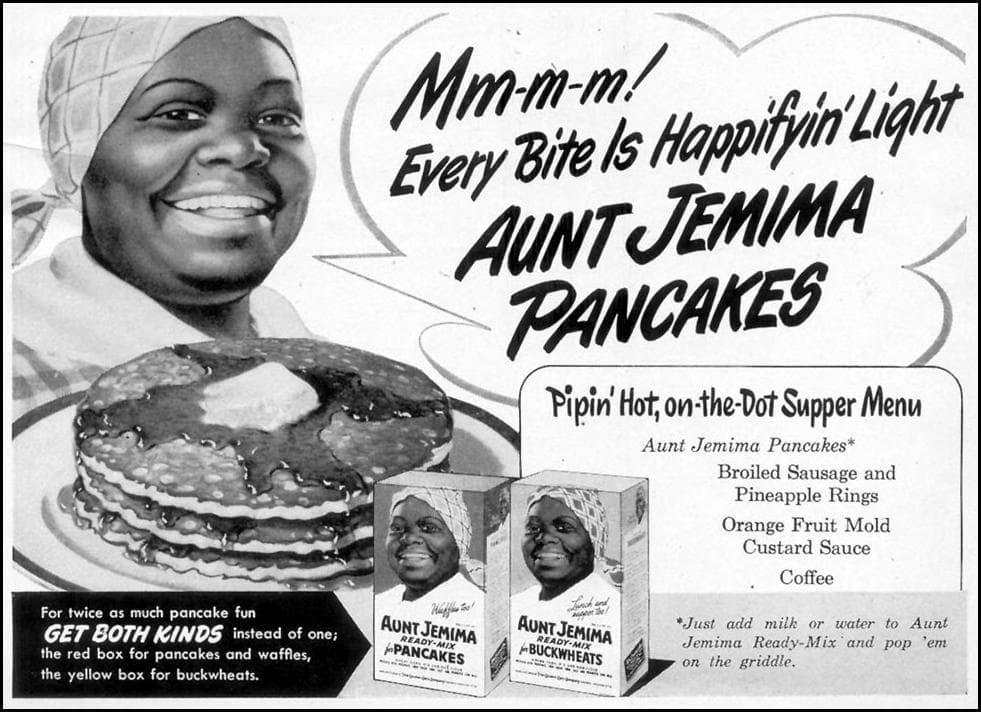

It’s an image of black servitude etched deeply into the American psyche: a robust woman of dark complexion, a scarf tied around her head.

She was called Mammy or Aunt Jemima — a stereotype of black womanhood that could be found everywhere: in movies, cartoons and commercials; in the form of syrup bottles and figurines on kitchen counters.

Still, the last place Dora Robinson expected to find Aunt Jemima was along a back road in upstate New York.

“Ooh, she’s heavy,” Robinson said during a visit at her home. “Yeah, she probably weighs about five pounds. She’s heavy, very heavy.”

Robinson and her husband, Frank, had stopped at a yard sale — run by a white woman — when she picked up the rusted, dirty, cast-iron doorstop.

“I asked how much they wanted for it,” Robinson said. “I think they said $100, and I said, ‘Mmm, nah, would you take less?’ And they said, ‘No.’ And I said, ‘Nah, I’m not spending that.’ So we get in the car, and we’re leaving, and we go up the road, and I say, ‘Oh, Frank, I gotta have Aunt Jemima. She doesn’t belong there. Let’s go back and get her.’ ”

The Liberation Collection

Robinson is retired and grew up during the civil rights era. She's devoted much of her life to social and racial justice, serving on the boards of numerous organizations throughout the Pioneer Valley, including the Women’s Fund of Western Massachusetts and the Healing Racism Institute.

She’s filled her home with a vast range of artwork celebrating black beauty and human dignity. She has also collected a group of dolls and figures which tell a more harrowing story — not only of beauty, but of subjugation.

Robinson calls this her Liberation Collection. At the center stands the cast-iron doorstop she found in upstate New York, because no figure sums up the complex and insidious role of racial stereotypes quite like Aunt Jemima.

Commercials from the 1950s show how the Aunt Jemima stereotype was employed in service to the economic interests — and racial insecurities — of white Americans.

One commercial shows two white couples at a dinner party, discussing their Aunt Jemima pancakes cooked with sausage.

Advertisement

Using The Objects To Learn And Teach

“We recreated this kitchen that has literally hundreds of Aunt Jemima and Aunt Jemima-like images in it, and we have some of our best discussions there,” said David Pilgrim, founder and curator of the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia in Big Rapids, Michigan.

Pilgrim acquired his first racist object when he was 12 years old. At a fair in Alabama, he purchased a Mammy salt-and-pepper shaker, took it outside, and stomped it into the ground.

“The first piece I purchased I destroyed,” Pilgrim said, “but I’ve come to know and to believe that you can use — well, you can use any object that came out of racist ideology — that you can use it to learn, and you can use it to teach.”

Pilgrim’s new book is “Watermelons, Nooses, and Straight Razors,” published in December. He reminds visitors to his museum that the figure of Aunt Jemima is a fiction that was created to set limits on what a black woman could be.

Robinson has friends who would not want her Liberation Collection in their homes. And if her parents or grandparents would have come across her doorstop?

“They would have said, ‘Why you got Aunt Jemima around here? I mean, what’s that about?’” she said. “It’s not anything that they would go out of their way to acquire. In fact, if anything, the negative sort of shame and a legacy of slavery and post-slavery is the image that they have in their mind.”

For Robinson, there are many aspects of the Aunt Jemima representation she does not support. But she sees resilience in the figure and does not believe it should be discarded.

“She survived,” Robinson said. “As a woman, she survived the times, and I think I find strength in the fact that we survived, as a people, slavery.”

Robinson’s Liberation Collection has particular relevance now. The Confederate flag and memorials to Confederate generals have become hugely contested, with calls for the objects’ removal and destruction, as well as aggression from white supremacists trying to preserve the racist images’ power.

'The Triumph Of Dialogue'

Robinson said she understands the thrill in taking these monuments down, but she questions the urge to destroy them.

Pilgrim also said it's essential to keep the historical evidence, even the most offensive objects, and to make sure they're only shown in a context that inspires conversation.

“And quite frankly,” Pilgrim said, “if you give people that opportunity to talk, they will say some things that disappoint you. But if you believe in the triumph of dialogue, then you're OK with that.”

Robinson can handle the hard conversations. Holding up her weathered, rusty, cast-iron doorstop — her Aunt Jemima — she imagines what she’d do if, in a white person’s home, she came across another figure like this one.

“Do you think I would be bold enough to ask for her? Probably,” she said, and laughed. “Can I have her? You want to sell her? Donate her? Because she doesn’t belong here on your floor. Trust me.”

This story comes via the New England News Collaborative and was first published by NEPR.

This segment aired on January 15, 2018.