Advertisement

After A Tragedy Like The Marathon Bombing, What Do We Do With All The Stuff Left Behind?

Resume

As Boston's Copley Square gets ready for Marathon Monday, there are only a few reminders of the massive outpouring of grief that once stood there. On the sidewalk, someone's written "Boston Strong" on poster board, along with a pair of sneakers and a few American flags.

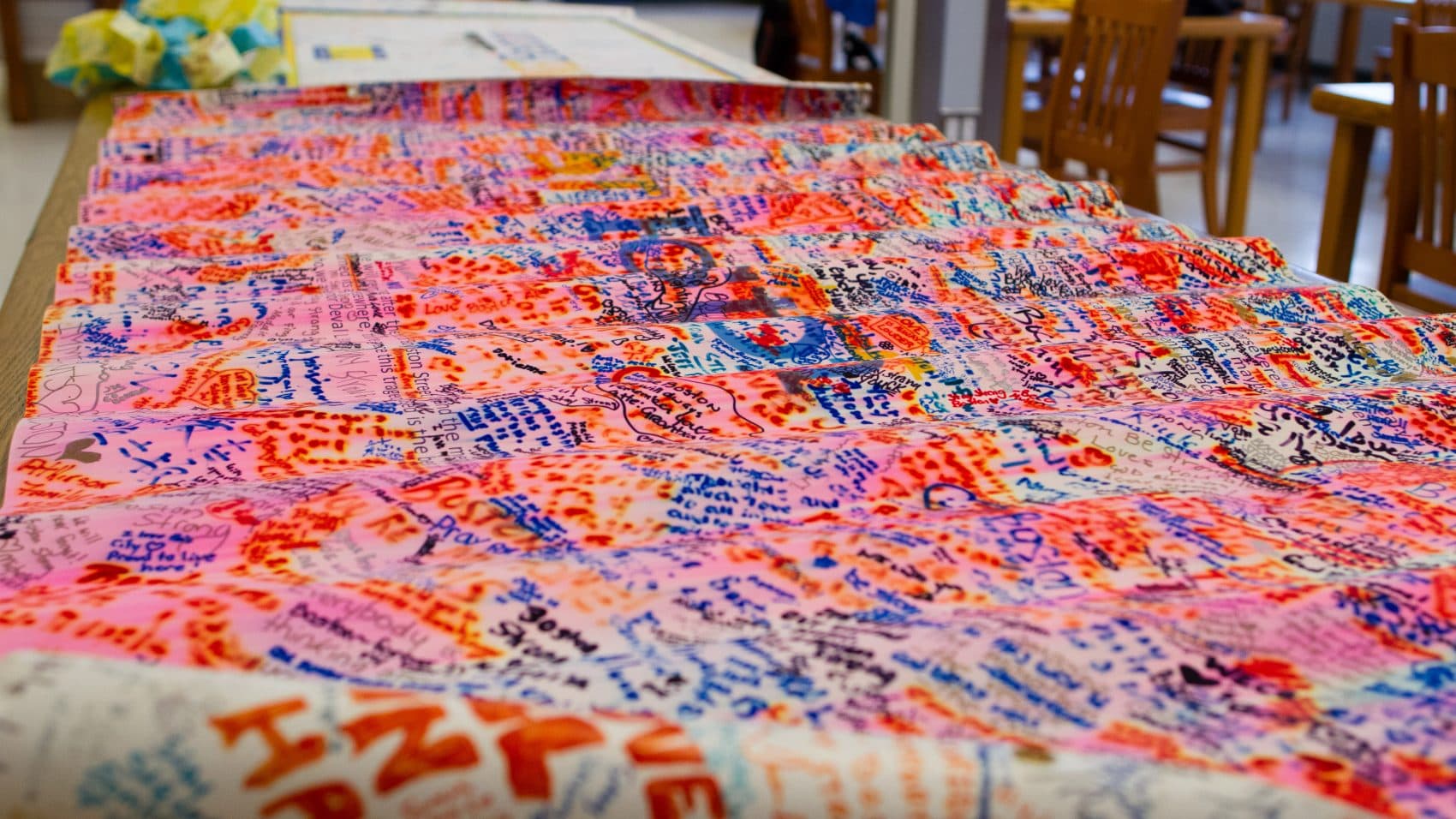

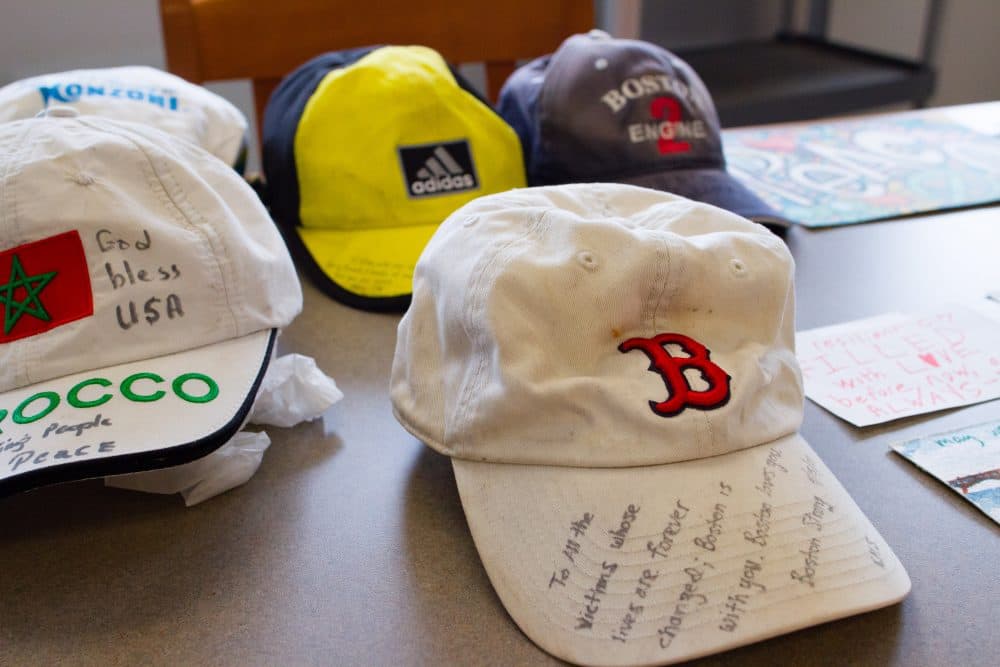

It's a fraction of what was there five years ago. For two months after the bombing in 2013, piles of shoes, race bibs, T-shirts, banners and stuffed animals lined metal barriers. It was an outward expression of the city's grief.

Today, many of those items sit seven miles away, in a climate-controlled warehouse in West Roxbury, at the Boston City Archives. The shelves are filled with the writings of Paul Revere and Josiah Quincy, alongside old maps and city council agendas on floppy disks.

Every shoe and race bib from the memorial in 2013 was painstakingly collected, cataloged and preserved by Boston archivists. In the city warehouse, there are a few hundred items, from posters to flags, plus 2,000 cards and letters that were mailed to then-Mayor Tom Menino at City Hall. Storage company Iron Mountain donated space to Boston and holds an additional 286 boxes, including 135 boxes of sneakers and 75 boxes of stuffed animals.

"It's such a unique operation," says John McColgan, the city archivist. "We've never done anything like this before. But it is an honor to be the custodian of this material here because it was such a profound event in the city's history. It cut real deep and for us to have this material here and to preserve it and to ensure that through generations we are able to see it is a great honor for us."

Among the items tucked into drawers is a large black poster with colorful chalk drawings -- a cloud and a sun, and a child's depiction of MIT's Great Dome, next to a cruiser that says MIT. A cross glows in the center, next to a heart. There's some children's handwriting on a lined piece of paper tacked to the poster board.

"My family and I have been cooped up in our house because we're not able to go to Boston because of some explosions," the note says. "We haven't been able to go anywhere because the city is on lockdown. [Lots] of damage was caused but we are already fixing everything. I feel happy because the two people who are causing damage were caught but I feel sad for all of the people who are injured."

He signed his name, Diego. His letter is part of the city's history, says archivist Marta Crilly.

"The items at this memorial show not only the response of Bostonians, but also just the outpouring of love and support that came from across the world."

city archivist Marta Crilly

"The items at this memorial show not only the response of Bostonians, but also just the outpouring of love and support that came from across the world to Boston," Crilly says. "It's a big part of our community's history and a big part of our community memory."

When two bombs went off at the finish line five years ago, Boston grappled with how to process its grief, and a handful of people had to figure with what do do with all the stuff left behind. Throw it out? Save it? How much, and where would it go?

It was a new experience for Boston. But they weren't new questions.

Planning For The 'Unthinkable'

Ashley Maynor is a professor and librarian at New York University who has studied this phenomenon — the act of leaving things at the scene of a tragedy, and what drives people to do it. She was an instructor at Virginia Tech in 2007 when a gunman killed 32 people in what was then the deadliest shooting in modern U.S. history.

These kinds of events aren't something cities want to plan for. But at an increasing rate, they keep happening.

"We're now seeing we have to start thinking about things that were previously unthinkable," Maynor says. "We have to be prepared for these worst-case scenarios and to decide if we should have a collection. What it should look like and what do the historians of the future need? That's what librarians are always trying to figure out."

On June 12, 2016, the unthinkable happened again, this time in Orlando. A gunman walked into the Pulse nightclub and killed 49 people.

Orange County Regional History Center chief curator Pamela Schwartz woke up that morning, saw the news, and got to work. She knew what would happen next.

"Memorials were going to start growing and there were going to be so many stories to be told here that needed to be recorded," she recalls. "And so I sat down and I just started writing."

That writing turned into a five-page plan, covering everything from making sure the items stayed in Orlando, to getting enough staff to collect and preserve them.

But issues emerged that she couldn't have predicted. Where would the memorials pop up? Who owns the mementos left behind? What do you do with letters of hate, or notes filled with conspiracy theories? What should they keep, and what should be tossed?

"You have to try to think about in 200 years, what is the curator going to say, 'Oh, man, I wish they had collected this thing,' " Schwartz says. "What is going to be the primary evidence and source documentation that this event was here? It happened. It affected this community permanently."

Schwartz and her team in Orlando are now part of a sort of rapid response collection fraternity. She called Las Vegas and Parkland archivists to share her knowledge, and her team is putting together a more formal toolkit that would help others in the immediate aftermath of a crisis.

All the archivists acknowledge that they're just guessing as to how to do this new and tragic job. And they know they'll be graded not now, but in the coming decades — the same way they're judging the archivists of Paul Revere's time.

No matter what choices the archivists of today make, Maynor says researchers of the future will get an uncommon glimpse into our history, recorded by the people who were there.

"These are everyday people expressing grief, expressing sympathy, showing love and goodness often in the face of hatred and violence," Maynor says. "And I think that's going to be a powerful testament to the kind of world that we are living in, with as many problems as we have."

In some other city, probably sometime soon, the cycle will repeat itself. Those who have been through it want to make sure that city's prepared.

This segment aired on April 13, 2018.