Advertisement

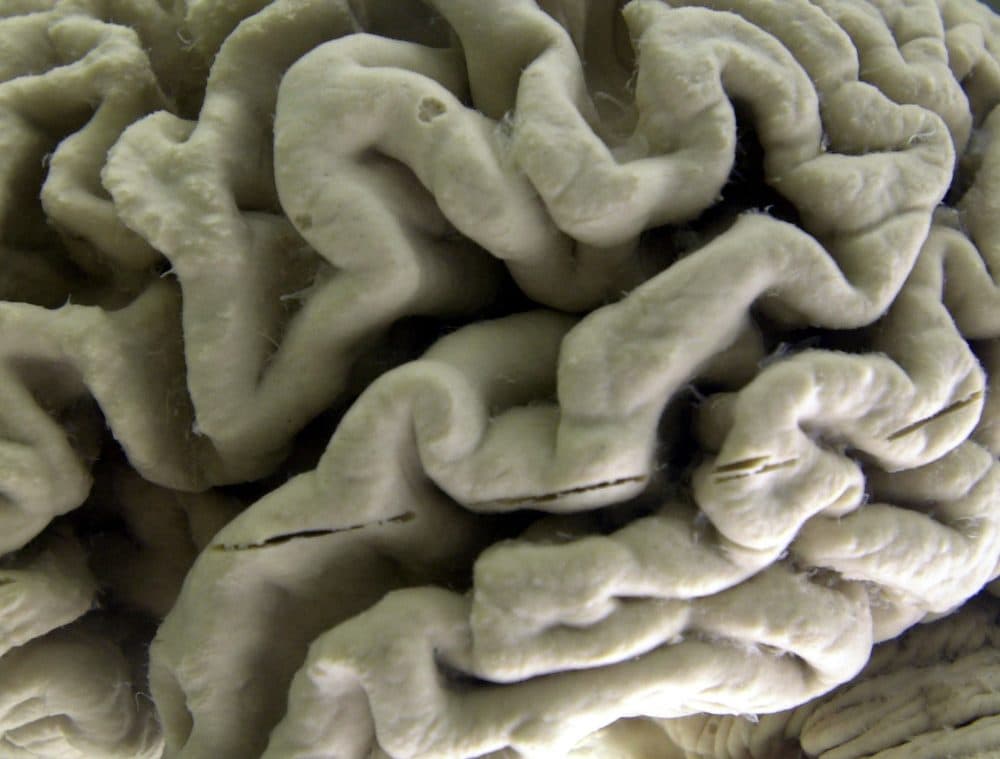

Mass. General Researchers: Can Medicine Mimic How Exercise Counteracts Alzheimer's Disease?

Exercise has been found to help prevent Alzheimer's disease. New research from Massachusetts General Hospital could help explain how — and suggests how medicine might someday mimic that effect.

Exercise brings on the birth of new nerve cells in the brain — a process called neurogenesis. The MGH researchers looked at whether inducing neurogenesis in mice with Alzheimer's could counteract the disease's effects.

"And when we tried to do this with drugs or gene therapy, it didn't work," says Rudolph Tanzi, a professor of neurology at MGH and Harvard Medical School and senior author of the research. "But interestingly, when we tried to do it with exercise, the mice got better — cognitively better."

The key seems to be that the exercise "cleans up" the environment that the new neurons are born into, reducing inflammation and helping them survive, Tanzi says.

The findings, out Thursday in the journal Science and funded partly by the nonprofit Cure Alzheimer's Fund, could lead to treatments that have the same effect in humans -- but that would take years, he says.

The cognitive improvements in the mice whose neurogenesis stemmed from exercise raised the question: "What's so special about exercise?"

The answer: New nerve cells born from other methods didn't survive. "It's like a baby born in a battle zone," Tanzi says, "and the new nerve cells die. And so it's not enough just to trigger new nerve cells in the brain, because they won't survive. But if you do so with exercise, they do survive. And that's because exercise, in addition, cleans up the battleground."

So could drugs or gene therapy mimic those effects of exercise?

Exercise triggers the production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, or BDNF, which helps nerve cells survive and cleans up local inflammation, Tanzi says.

After seeing that drugs and gene therapy failed to mimic the effects of exercise, "the next thing we did was very simple. We took the drug that induces neurogenesis that didn't work the first time, but we also gave a drug that turned on the BDNF, and voila! We were able to mimic exercise, and the nerve cells were born, they survived and the mice got cognitively better."

The drugs used are not ready for humans, he says, but that's the next step, and companies are already at work on relevant gene therapy and medications.

Dr. Sam Gandy, a leading Alzheimer's expert who is based at Mount Sinai School of Medicine and was not connected to the study, says the findings also suggest that the power of exercise depends on more than BDNF.

"We used to think simplistically that exercise was working on the brain primarily through BDNF and that was the end of the story," Gandy says. "So clearly the story is more complicated than that."

The study also "establishes the principle that there could be a pill, an oral pill, that you would take that stimulates neurogenesis," he says. But adding BDNF to the mix is trickier: In the lab, it is normally delivered by being injected into the brain "and that's not very convenient for humans, especially if you want to have it every day."

For now, Tanzi says, "exercise is a great way to help reduce your risk for Alzheimer's disease."

And though this has not been proven in a clinical trial, "if you're in the early stages and you exercise more, the belief is that it will help slow down the disease."