Advertisement

Lowly In Stature, Fungi Play A Big Role In Regulating The Climate

Resume

As fall approaches, you may have noticed there's plenty of fungus among us.

A rainy spring and hot, humid summer have produced an early, bumper crop of fruiting fungi we call mushrooms.

Fungi are among the most tenacious forms of life, on or off the planet. They've been found growing outside an orbiting spacecraft, thriving inside the ruins of the Chernobyl reactor, even in rocks in Antarctica.

But it's on forest floors where fungi reign supreme. Biologically distinct from animals, plants and bacteria, fungi are classified with their own kingdom.

And in our world, they play a critical role in regulating the global climate.

Foraging For Fungi

Walking through a forest in Wellfleet, decaying leaves and fallen twigs snap and crunch underfoot. The sandy loam soil anchors stunted oak and pine. It's a perfect place for mushroom hunting.

"I love Wellfleet. ... This is my favorite town to be in on the Cape in mushroom season," says Wesley Price. He builds high-end homes on Cape Cod, but come fall, he forages the forest searching for mushrooms.

The above-ground fruit of some species of fungi come in a wild variety of shapes, sizes and psychedelic colors.

He points out what he calls "a great mushroom." He says it's a "velvet-footed pax. That's a paxillus atrotomentosa."

That's easy for Price to say: He's been studying and foraging mushrooms since college and is founder of the Cape Cod Mycological Society.

"It takes a unique personality type to want to walk through the woods and collect your food," Price says, before pointing at fellow foragers.

That includes my family and me. We are in a spot in Wellfleet that is a jealously guarded secret that attracts in-the-know Eastern European mushroom hunters. My father-in-law is armed with a short knife and wicker basket, and points out a mushroom to Price and me.

"Yeah, now this is a Gypsy mushroom. This is a great edible mushroom," Price says. "I love this one." He gives us the scientific name: "Cortinarius caperatus."

And it's good eating.

"Oh yeah, it's not a beginner mushroom," Price adds. "If you don't know about mushroom stuff this could be confused with other poisonous species."

People can eat only a few types of mushrooms, but some species of fungi can eat just about anything — from nerve gas to plastics. Fungi and bacteria are nature's recyclers. They feast on dead and decaying plants and animals, transforming the fungal food into essential nutrients and elements plants require.

"I think we're just beginning to understand how critical they are," Price says, "because of the ecological balance they maintain. If you have a healthy soil with plenty of fungi and microbes you have the pieces that are necessary to support life."

Subterranean Climate Warriors

No fungi means no life. The fate of the Earth's climate literally hangs by threads produced by fungi. These ultra-fine filaments of cells help forests store climate-changing carbon in the ground. The complex process is not well understood by scientists, who estimate there are as many as 3.8 million species of fungi, but so far they've identified just 120,000.

"Six lifetimes wouldn't be enough to explore the kingdom of fungi because there are so many species of fungi and so few people studying them," Price says.

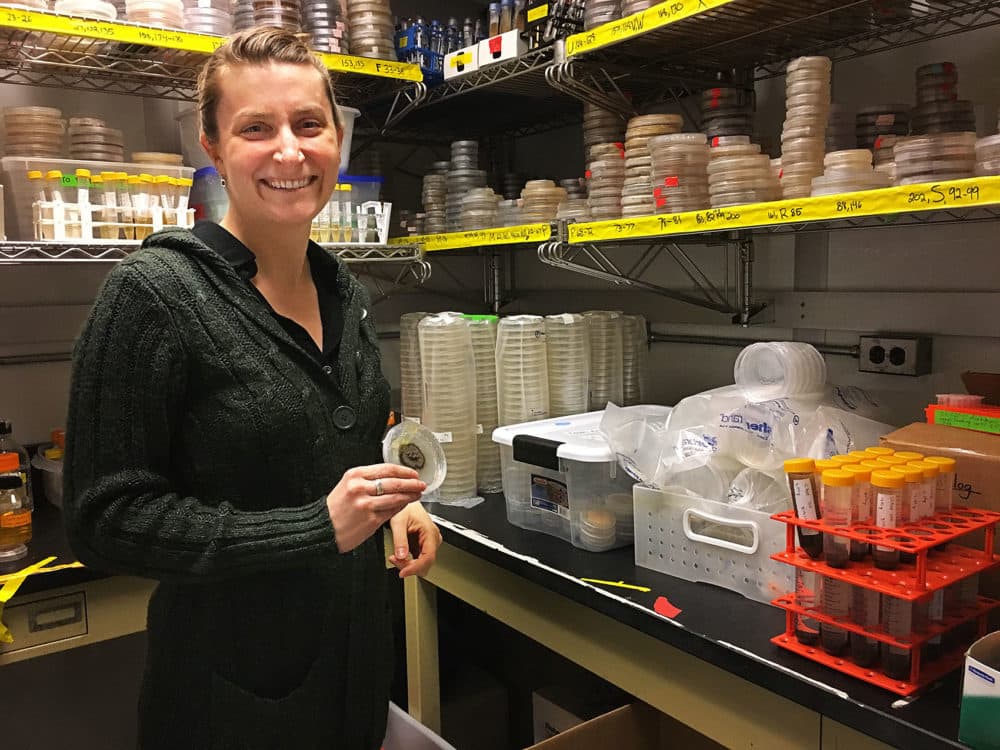

Boston University chemist Jennifer Bhatnagar is one researcher studying fungi and climate change.

"The real area where fungi are influencing climate is by influencing the amount of greenhouse gas in the atmosphere," she says.

Bhatnagar says just a tiny pinch of soil can contain several hundred fungal species — many that help regulate global-warming emissions.

"The way they do this is pulling CO2 out of the atmosphere and storing it below ground," she says.

Thanks to fungi there's twice as much carbon locked in the ground as in the atmosphere. One square meter of healthy soil can contain 12,000 miles of tangled fungi filament.

"So essentially the more fungi grow in soil, the more carbon dioxide [that] can be drawn out of the atmosphere," Bhatnagar says.

Fungi are subterranean climate change warriors — minute chemical factories that produce an array of powerful enzymes.

Bhatnagar keeps hundreds of species gathered from around the world stacked in petri dishes, ready to serve science.

Growing fungi in a lab is difficult because it's impossible to replicate the complex community of plants and microorganisms that communicate chemically in a forest. In nature it's a delicate network that depends on the temperature of the soil.

"So climate change is really disrupting these communities and their ability to cycle carbon and their ability to store carbon potentially," Bhatnagar says. "That's an area we're trying to understand more."

BU professor Pamela Templer tries to make the complex fungi-climate connection simple. She draws a picture of what scientists call the carbon cycle: the interaction of trees, fungi, soil and sky.

Templer is a forest ecologist. She's especially interested in what are called mycorrhizal fungi. These play a critical role in the carbon cycle for about 85 percent of plant life.

Thanks to fungi there's twice as much carbon locked in the ground as in the atmosphere.

"If some alien came in and zapped all of the mycorrhizal fungi and they disappeared," Templer says, "I think we'd see a major shift in what plants we see around here."

Today, we're the aliens. When we burn fossil fuels, we pollute the air with nitrogen, which rains down on forests and acts like fertilizer upsetting the mycorrhizal fungi's ability to store carbon. The CO2 that's emitted from the fuels also creates a greenhouse effect; the atmosphere and soil heat up.

"When it's warmer," Templer says, "we see faster rates of decomposition of all those branches, roots, leaves, frogs, birds, whatever — anything that was alive that's on the forest floor — and an increase in how much carbon dioxide is leaving the soils, no longer being stored there, boom, going back into the atmosphere."

It's a forest-destroying, climate-disrupting feedback loop — warmer temperature, less snowfall. Exposed ground in winter freezes faster, deeper, longer — stunting tree growth and the storage of carbon.

"Overall we're seeing a greater increase in soil losses of carbon dioxide," Templer says. "The net effect is what we're trying to quantify right now."

Preliminary results from Templer's experimental plot in a New Hampshire forest suggest that if scaled up for the entire New England region, the amount of carbon stored by fungi in forest soil would be reduced by 20 percent, further accelerating the climate change feedback loop and increasing the possibility of runaway global warming.

Again, mushroom expert Price: "We live on a very delicately balanced planet. We're really fragile, we're much more fragile than we think we are."

If Earth has a future, the lowly fungi — unseen, underfoot and still not well understood — will play a crucial role in maintaining that delicate balance.

Correction: Due to a reporting error, Pamela Templer's name was misspelled. We regret the error.

This article was originally published on September 18, 2018.

This segment aired on September 18, 2018.