Advertisement

These Boston Artists Use Mangos And Mariposas To Address Anti-Blackness Among Dominicans And Haitians

The first time artist Chanel Thervil ate a Haitian mango, she could practically hear her ancestors cry, she recently said with a laugh. “Haitian mangos have a very specific, important cultural context. I have relatives that joke about Haitian mangos being like gold.” Their color, a bright, dazzling yellow, represents hope and strength, she said.

Mangos are also one of the only things that unifies the Dominican Republic and Haiti — two countries still reeling from racism that stems from their fraught colonial history. Thervil and fellow artist Iris Lapaix have unpacked some of that complicated tension through an interactive art exhibit in Boston's Latin Quarter.

“Mariposas and Mangos” uses art and food to bridge cultural gaps in the Afro-Latinx community during Hyde Square Task Force’s celebration of Latinx Heritage Month. The two-part unveiling ceremony on Saturday, Oct. 13 features large interpretations of mangos and butterflies fashioned out of wood, along with other works of art. Viewers will be invited to add their own cultural stories as a permanent extension to the artwork.

“As a Dominican-American and Chanel being Haitian-American,” Lapaix said, “we thought, what better way to bring people together than art, while bringing the element of history with it.”

The Dominican Republic and Haiti, two nations that occupy an island smaller than South Carolina, have pasts steeped in the violence of colonialism.

The first European settlement in the New World was established on the island by Christopher Columbus in 1492 and claimed by the Spanish. In 1697 after the Treaty of Rystwik, Spain ceded the western third of the country to France, who established it as Saint-Domingue, now known as Haiti.

How the two imperial powers treated their colonies determined the divergent futures of each country. The French ruled Saint-Domingue through brute force and exploited the abundance of natural resources and the labor of hundreds of thousands of African slaves. Through unsustainable agricultural practices, the French decimated the land, making much of it unusable for generations to follow. On the eastern side of the island, in Santo Domingo, the Spanish took a different approach and established control through converting and assimilating the indigenous and slave populations into Spanish culture.

Advertisement

A study of Haiti's history is an exploration of the tangible, generational harm of global racism. In 1804, when Haiti won its independence and abolished slavery, France ordered its former colony to pay a sum of $90 million gold francs, worth roughly about $17 billion today, to recoup loss of land and labor — which really meant enslaved people. It took the newly sovereign nation more than 100 years to pay back the inordinate debt, a debt that crippled Haiti’s developing economy and infrastructure. Colonial powers such as the United States, frightened by Haiti’s slave revolution and what it could mean for their own slave based economies, further stunted Haiti by enacting trade embargoes.

In contrast, the Dominican Republic, unhindered by millions of dollars of debt, experienced economic growth and to this day, possesses better economic infrastructure, more generational wealth and longer life spans.

Mariposas, Spanish for butterflies, and mangos were chosen by Lapaix and Thervil for the breadth of their historical and cultural importance, especially in the Dominican Republic and Haiti. These symbols, heavy with nostalgia, serve as gateways to beginning conversations about painful shared histories and the sweetness of the future.

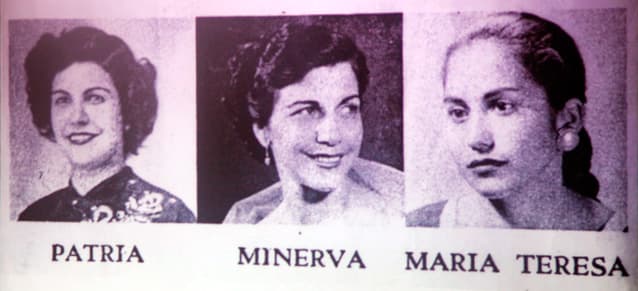

Mariposas, like mangos, are found on both sides of the island but they have a historical connotation for Lapaix. The Mirabal Sisters, known by their underground name as the Mariposas, were political activists and radicals during Rafael Trujillo’s dictatorship over the Dominican Republic. “The sisters became more militant after one of them witnessed the massacre of Haitian migrants at a religious retreat,” Lapaix said.

Trujillo would go on to order a genocide, killing more than 20,000 Haitians living in the Dominican Republic in 1937 in his attempts to “purify” the Spanish speaking side of the island. The Mirabal sisters became involved in underground activities that sought to topple Trujillo’s regime but ultimately, three of the four sisters paid for it with their lives. “Trujillo assassinated them,” Lapaix explained. “But what he ended up doing was turning them into martyrs we remember to this day.”

Trujillo’s regime is still a fresh, festering wound in the relationship between Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Lapaix pointed out that while time has passed, some attitudes about Haiti have not. “I have older family members who still believe in his (Trujillo’s) vision,” she said. In the 57 years since Trujillo’s assassination, relations between the two sides of the island have improved but anti-blackness and anti-Haitian sentiment have proven to be resistant and resilient viruses.

In 2013, the Dominican high court passed a ruling that essentially stripped Haitian descendants living in the D.R. of their Dominican citizenship. Nearly two years later in 2015, reports began coming in that the D.R. was gearing up to deport those who lost their citizenship back to Haiti, which was still recovering from the disastrous earthquake of 2010.

This history of anti-blackness and anti-Haitian rhetoric has created a divide that reverberates throughout time and culture. Thervil and Lapaix are hoping to stitch threads of understanding between the two cultures to mitigate this.

“Because of this tension that exists, many Haitians and Dominicans kind of shy away from each other and shy away from talking about that tension,” Thervil said, “Even though we share a lot cultural similarities.”

Boston boasts large populations of both Haitians and Dominicans and the influence of the two on the city’s culture is clear. All one has to do is be on Blue Hill Avenue during Haitian Flag Day in May or out in the streets during Boston Carnival. The mission of “Mariposas and Mangos” is to expose those similarities and to use them as a vehicle for cultural exchange and discussion.

“The point is that two things and two cultures can exist together,” Thervil pointed out. “And it can be a positive exchange.” Both artists designed the exhibit to enhance and build on those “positive cultural exchanges” to encourage members of the community to talk and get to know each other.

Exhibit goers can expect a two part experience that explores the art and invites them to break metaphorical bread with an exchange of fresh mangos. “I’m a firm believer that once you break bread with someone, your relationship is on a different level,” Lapaix said. Attendees will also be encouraged to share their own cultural stories in a way that directly interacts with the artwork. “It's about providing people with sustenance," Thervil told WBUR. “For your belly and for your heart and for your brain too. Everything.”

“Mariposas and Mangos” will be available for viewing outdoors during the unveiling event on Oct. 13. After that, the exhibit will be installed for indoor viewing at Hyde Square Task Force. While the art isn’t a permanent public piece, its impact is more far reaching than its corporeal presence.

“Community engagement with artwork is important,” Thervil emphasized. “It can transform culture as we know it.”