Advertisement

How Massachusetts Helped Win 'The Great War'

Resume

This Sunday, Nov. 11, will mark 100 years since the end of World War I.

"The Great War" — or "The War to End All Wars," as it has been called — saw more than 70 million men from dozens of nations — and their colonies — mobilized to fight.

The United States would begin the war with just 300,000 men in the Army and National Guard, but by the end of the conflict would see more than 4 million military personnel mobilized to fight or support military operations.

Ralph Murray, of South Boston, was one of those mobilized to fight.

"I enlisted in Company A, 8th Infantry, in Cambridge, Mass., on July 5th, 1917," he said in a recording made in 1967.

Sgt. Murray served in the Yankee Division, the 26th division of the National Guard, comprised of 28,000 men all from New England. The Yankee Division, depending on which source you ask, was one of the first, if not the first, fully formed divisions to arrive in France. By February 1918, they would be sent to the front lines, about 200 miles east of Paris.

"All around, the villages, they were blown up. The trenches were all smashed, and we had to repair them — always under shell fire," Murray remembered. "The first time the shell came over to us with a whine and landed about 50 feet behind us. We sure were scared, and if anyone says they wasn't, they are full of baloney."

Murray was on the front lines until July 20. That was a hot summer day with temperatures in the low 90s, he remembers. And he remembers charging through a wheat field with stalks up to his waist when he was severely injured.

"We were charging the machine gun position when my gun was knocked out of my hand, and I was hit in the right knee, and I received a flesh wound above my left knee," he said. "My canteen was shot off the hip. I fell and lay there, and a buddy by the name of Bates came along. [He] asked if I was all right. I said if he would help me I would try to walk."

Murray had a compound fracture — the bone sticking out of his leg. But he and Bates made it to a nearby shell crater until medics could arrive. He'd miss much of the rest of the war.

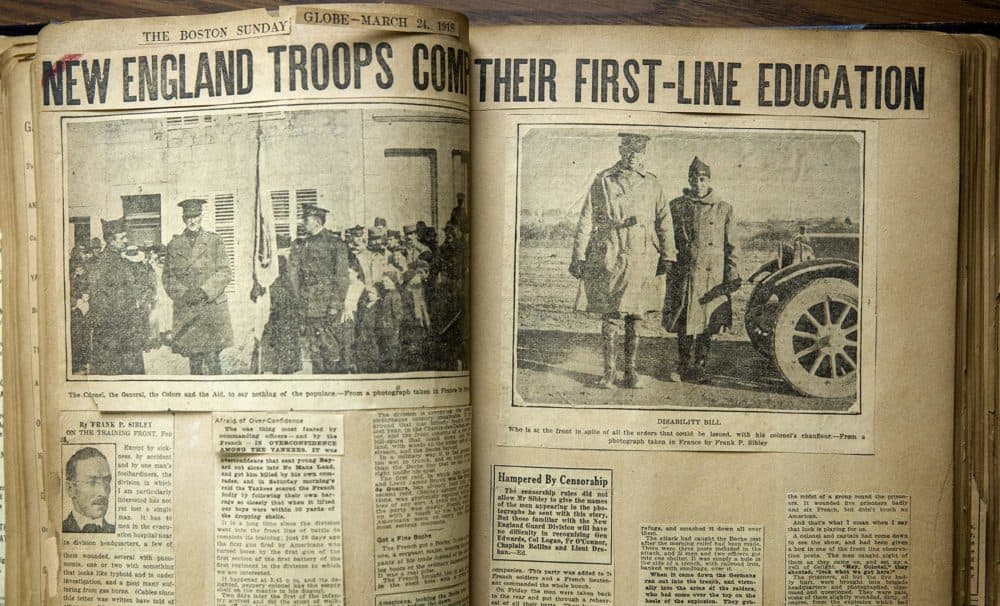

That recording was donated to the Massachusetts National Guard Archives & Museum in Concord, where Brig. Gen. Leonid Kondratiuk flipped through an old book of newspaper clippings. The paper's yellowed and it flakes to the touch, which isn't surprising, since these clippings are all more than 100 years old.

"We don't know who was clipping these and gluing them into the book," Kondratiuk said. "But there's a little bit of everything."

The clippings track the goings-on in Europe as American troops fought in their first European war — joining England, France and others in the war against Germany, Austria-Hungary and the rest of the Central Powers.

It includes articles about the mobilization of American forces, their deployment overseas, even a large headline reading "Russia Forced to Sign Peace," with the body of the article misspelling Vladimir Lenin's name.

"These clippings are from various newspapers," Kondratiuk said. "Boston had probably eight to 10 newspapers back then. Not just the Globe, there were many others. Every newspaper in New England had a story about the Yankee Division several times a week, because they were the hometown boys."

By the spring of 1918, the Yankees would see some of the first combat that American troops saw in Europe at the Battle of Seicheprey, near the French city of Metz (then a part of Germany). Outnumbered about seven to one, facing German stormtroopers, the 26th would hold its own.

"They were basically trying to get prisoners and bloody the Yankees' nose, but the Yankees gave as good as they got, and there were probably 400, 500 casualties on both sides," said Michael Shay, the author of "The Yankee Division in the First World War: In the Highest Tradition."

Shay's also a grandson of one of those soldiers who served in the 26th.

Seicheprey wasn't a total victory, he said. The Germans would briefly push American troops back. They would take nearly 200 prisoners. And 81 troops — all from Connecticut — were killed.

Shay said the American commander in Europe, Gen. John J. Pershing, would accuse the 26th Division commander, Clarence Edwards, of not being prepared.

"Pershing was just livid," Shay said. "He blamed Edwards for not being alert, and putting too many men on the front line, which was just absolutely wrong."

The 26th would spend most of its deployment time on the front lines. From that early battle at Seicheprey, to Belleau Wood (where Sgt. Murray was injured), to the Saint Mihiel Offensive — which began the morning after another New England favorite, the Red Sox, won the 1918 World Series.

The 26th and others involved in the attack would catch the Germans in a retreat, and take 15,000 German prisoners.

But Shay said the division would take a secondary role in the final offensive: the Meuse Argonne, which began about two weeks later. Still, Shay says that doesn't mean they didn't take casualties.

"They had companies that were reduced to 50 men," he said. "I mean, this is something that started out at 250 men. They had battalions that probably would've had hundreds of men in them and they were reduced to just mere shells."

Back home, as odd as it may sound, the Yankees were beloved in New England. But they wouldn't be the region's only contribution to the war effort.

Anatole Sykley is a member of the World War 1 Historical Society and the Organization of American Historians. He says the Charlestown Navy Yard — then known as the Boston Navy Yard — outfitted nearly every ship headed out to sea to fight in the new, 20th-century manner.

"The Boston Navy Yard was the oldest navy yard in the country, so it wasn't really well-suited for modern warships, but they found a niche," Sykley said. "Warships in those days had to be fitted with electronic gear for the first time — radios. So American destroyers, American submarines, battleships and cruisers had to come, had to be fitted with this new technology, before they would sail over to Europe."

It wasn't just Boston. The Fore River Shipyard in Quincy would produce 71 destroyers over the course of the war — more than any other American navy yard.

And it wasn't just naval warfare. MIT put together one of the country's first flight schools to teach American pilots the lessons that Europeans had been learning in real time for the last three years.

"If you can imagine two curtain rolls," Sykley said, "and a map would be painted on a continuous curtain roll, and a guy would sit up in a chair suspended from the ceiling, he'd put on his goggles and look down through a visor, and somebody would crank the curtain roll to simulate him flying over the enemy trenches."

The war would end on Nov. 11 — now known as Armistice Day, Remembrance Day or, in the U.S., Veterans Day.

Germany and the Allies would sign the Treaty of Versailles, and the men of the 26th would return home, where they'd be greeted with a ticker tape parade in the spring of 1919.

"Twenty thousand soldiers march," Kondratiuk said. "It's the largest military parade in Boston history. It is also the largest crowds in Boston history. Over a million spectators, because it's the hometown unit coming back. They're being greeted by friends and relatives and so on from all over New England, they take the train to Boston."

Kondratiuk said a crowd like that would not be replicated on the streets of Boston until 85 years later, when the Red Sox won the 2004 World Series and broke that infamous curse that started while the Yankee Division was deployed on the front lines.

This segment aired on November 8, 2018.