Advertisement

Review

Commonwealth Shakespeare Company's 'Universe Rushing Apart' Talks, Then Tumbles Its Way Into The Void

In “Universe Rushing Apart: Blue Kettle and Here We Go,” first language and then the human person — body and soul — break down.

Comprising two short plays by revered, 80-year-old British playwright Caryl Churchill, the concisely fragmented double bill being presented by Commonwealth Shakespeare Company and BabsonArts at Babson College’s Sorenson Black Box (through Nov. 18) stretches across two decades to showcase the ways in which Churchill’s unfettered imagination has the power to spur one’s own. Spare and loosely structured, the two works — one reminiscent of Ionesco, the other of Beckett — have in their crosshairs the mysterious nugget of humanity that remains when words, and even breath, fail us.

The prolific author of “Top Girls” (which was staged by the Huntington Theatre Company in April), “Cloud Nine” and “The Skriker," among other works, Churchill did not intend these plays to be performed together. Initially, “Blue Kettle” appeared on a 1997 double bill with the funnier if similarly surreal “Heart’s Desire.” By the time “Here We Go,” a triptych as whittled down as a Giacometti sculpture, was unveiled at England’s National Theatre in 2015, even a Churchill nodule was considered event enough.

Presumably it was Bryn Boice, who helms the CSC bill, who perceived that the two works, both of which play on the suggestibility of memory, might illuminate each other. And in a minimalist production ostensibly if imperceptibly influenced by “2001: A Space Odyssey” and the photography of Diane Arbus, the pairing proves, despite nods to purgatory and the pearly gates, less mordant and/or uplifting than tender and exhilarating.

At the center of “Blue Kettle” is a placid con artist called Derek, who has made a “hobby” (as girlfriend Enid terms it) of presenting himself to older women who long ago gave up babies for adoption as their long lost son. Derek is convinced “there’s money in it,” though we never see any materialize. But Enid thinks it may just be a weird “hang-up” inspired by his real mother’s dip into invalidism and dementia.

Whichever, Derek gently preys on the emotions of four variously vulnerable elder women in a series of short scenes in which precise if truncated language crumbles until meaningful phrases are replaced by the words “blue” and “kettle,” devolving in the end to mere puffs of “buh” and “kuh.”

“Here We Go” is a three-part endgame in which funereal banalities give way to what King Lear would call “the thing itself.” The British critic Michael Billington dubbed the play, in which there are echoes of the medieval morality play “Everyman," a “memento mori for an age without faith.”

Yet in the triptych’s second part, the bases of various creeds (heaven, Valhalla, samsara) are hit as a man in a nightshirt arrives in the afterlife filled with trepidation and regret, recalling of the Judeo-Christian touchstones: “but I don’t believe anything like...” And later: “and I think they don’t emphasize hell these days but you can’t be sure because there’s nothing kind about the universe just rushing apart."

This glimpse of a soul in confusion is sandwiched between the archly stylized funeral party from which the play takes its name, awash in guillotined snippets of the customary verbiage, and an almost mute depiction of near-death in which a caregiver repeatedly and laboriously prepares a frail old man for sleeping and then waking and then sleeping again.

Boice stages the two plays on an almost bare stage where ensemble members dressed in scrubs scoot white Styrofoam set pieces into different arrangements. Sound designer Dewey Dellay’s score — which ranges from the anxious to the magisterial but is never overwhelming — provides an emotional barometer as an excellent ensemble of five goes through the absurdist motions of the plays, supplying both ironic commentary and genuine emotion that the linguistic trickery might in lesser hands obscure.

In “Blue Kettle,” Ryan Winkles is an impassive Derek, less callous or malicious than plain curious about what will come of the web he weaves. Sarah Mass is the voice of insolent, exasperated reason as Enid. And as the various moms, a stony Siobhan Carroll, a fluttery if sharp-edged Maureen Keiller and especially Karen MacDonald as a couple of maternal marks, one shy and soft-edged, the other a regular gyrating Phaedra, are never less than nuanced and comprehensible, no matter how deeply they dive into the blues and kettles.

Churchill spells out even less for director and actors in “Here We Go,” whose first segment, on paper, consists only of lines and phrases to be dealt out to the players like cards. But the CSC actors, all playing women attending the funeral of a man who might have been lover, acquaintance or friend supply reams of subtext, some of it solemn, some of it catty.

Every once in a while, a mute figure appears with a top hat into which one funeral attendee after another dips as if for a fortune before stepping forward to fill the audience in on the details of her own impending demise. As was the case in “Blue Kettle,” the performers promenade among the movable set pieces, brandishing wine glasses and flutes as opaque and unreal as the furniture.

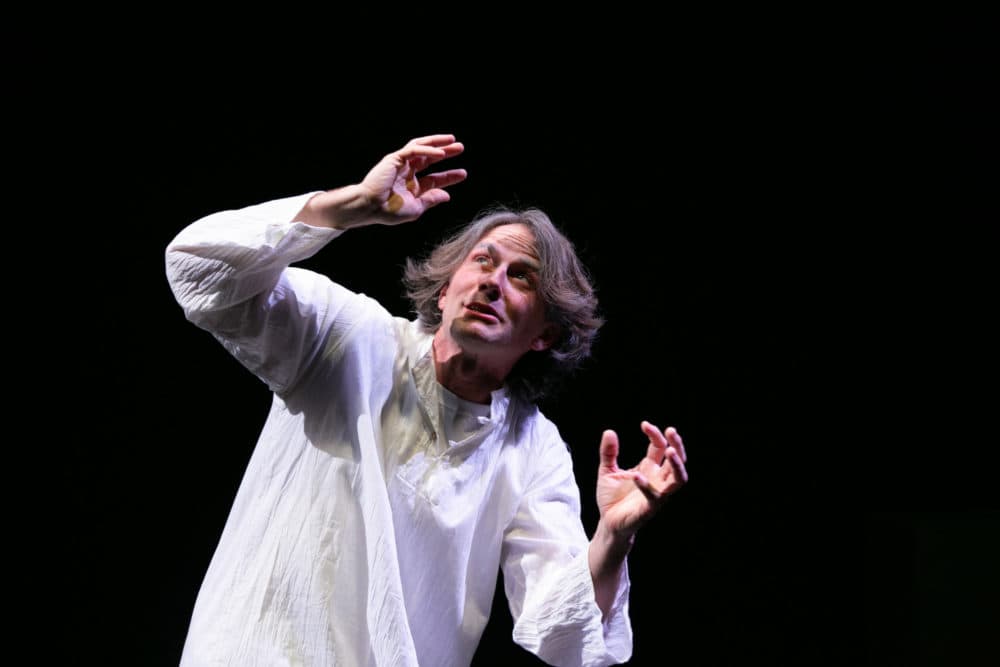

The long monologue, simply entitled “After,” falls to Winkles, who brings to this free-associative riff on life, death and the desperation for a second go a dizzying if lightweight virtuosity. (In the 2015 premiere, a much older actor assayed the remarkable if disjointed speech.)

Winkles, his head pushed forward as if his neck were frozen, his fingers curled as if painfully arthritic, also portrays the near-vegetative invalid of “Getting There,” Carroll his brisk but gentle caregiver. As the scrubs-clad attendant repeatedly pulls her limp charge to his feet in order to swap out sweater for bathrobe, slacks for pajamas, to which his response is limited to an agonized grunt or a lip quiver, you realize that their impersonal embrace has been the most intimate human contact of the two-part evening.

Having nimbly demonstrated language going to hell in a kettle, Churchill makes us question whether we need it.

"Universe Rushing Apart: Blue Kettle and Here We Go" continues through Nov. 18.