Advertisement

A new documentary looks at Myles Connor, a rocker among thieves

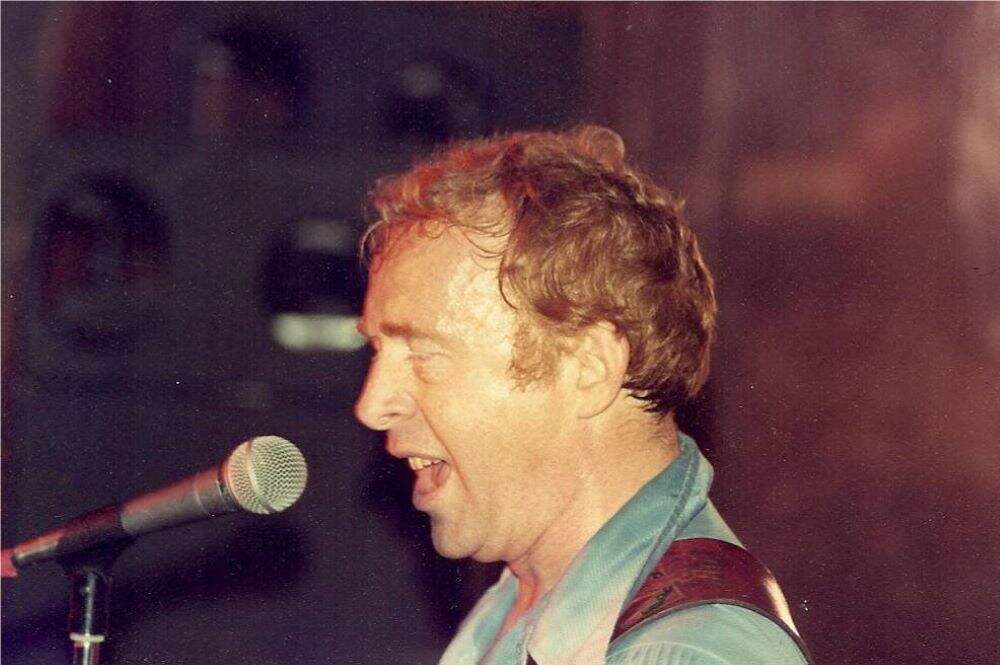

In the early 1970s, filmmaker Bruce Macomber went to see a band play at the Baggy Knees, a ski resort bar in Stowe, Vermont. It was the heyday of psychedelic rock, and Macomber’s friends couldn’t understand why he’d want to “go see this greaseball” who was playing the ‘50s rockabilly of Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee Lewis. The lead singer began the show by riding a motorcycle onto the stage. “There was a palpable sense of danger, this crackle in the air,” recalls Macomber, who couldn’t understand why “this wasn’t happening on a bigger stage.”

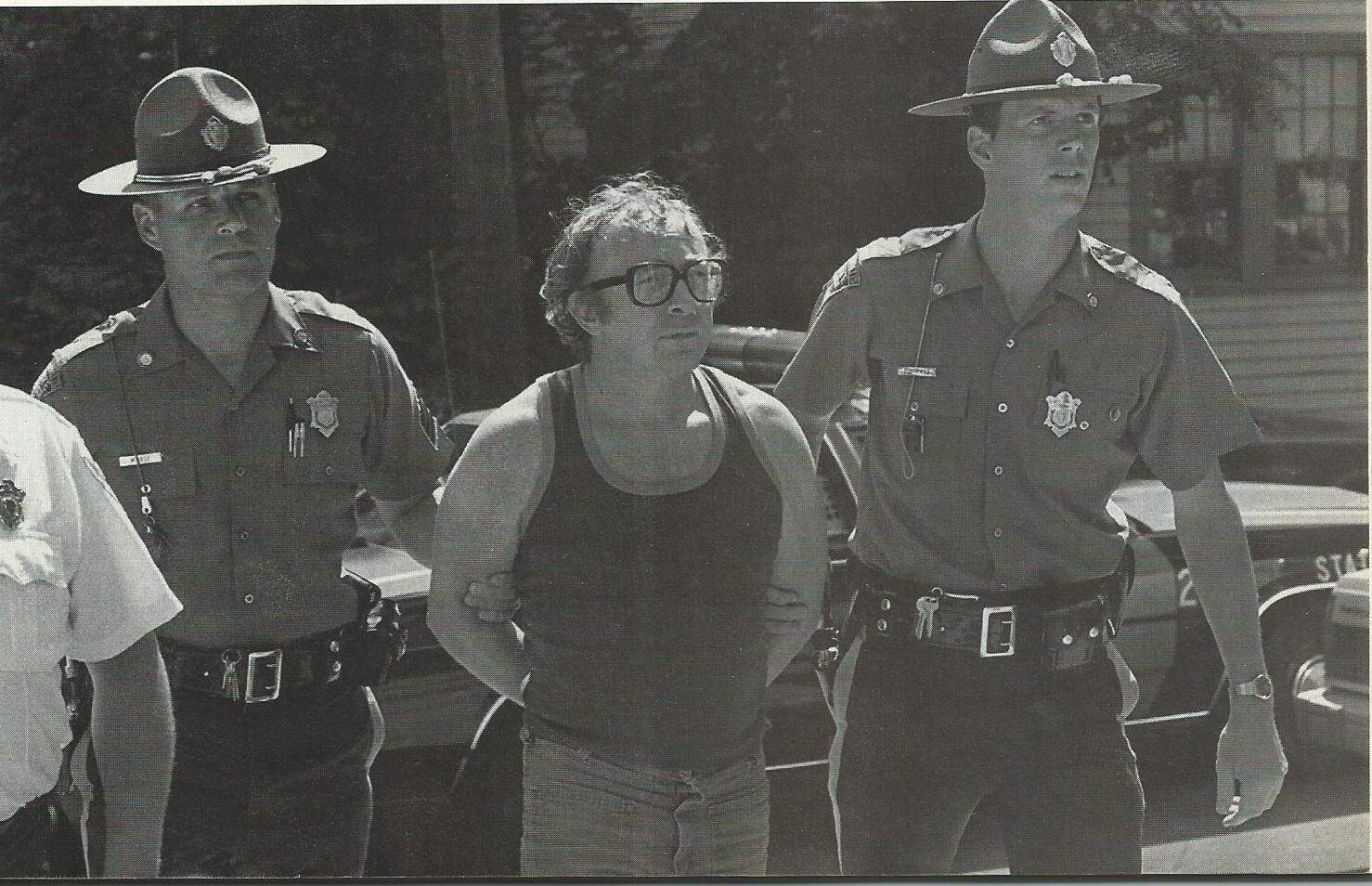

The answer was that Myles Connor was getting famous for something other than rock ‘n’ roll. In 1974, Connor, who’d already been in and out of jail for years, stole paintings by both N.C. and Andrew Wyeth from a Maine mansion. After being arrested for trying to sell the paintings, he stole a Rembrandt from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, to use as a bargaining chip for a reduced sentence of 28 months. When that prison stint was finished he returned to the rock circuit, playing roadhouses like the Beachcomber in Quincy with his band The Wild Ones. When the infamous 1990 theft at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum took place, Connor was in federal prison on drug charges. That didn’t stop him from becoming both a suspect and a staple of books, podcasts, and TV shows about the heist.

Now Connor is the subject of “Rock ‘n' Roll Outlaw: The Ballad of Myles Connor,” a film that looks at his life of crime and his music. In the works since 2009, the film is having its Boston premiere at the Regent Theater in Arlington on Sunday. A post-screening panel will include Connor and figures from both of his career paths: His longtime bassist and manager Al Dotoli, and the Gardner’s security chief Anthony Amore.

Dotoli, Connor and Macomber recently gathered at the David Bieber Archives’ Norwood warehouse. Bieber pulled out a photo of Dotoli and Connor taken at the Donnelly Memorial Theater in Boston in the mid-’60s, an era when they were regularly appearing with the likes of Roy Orbison, the Beach Boys, and the Dave Clark Five. Arnie “Woo Woo” Ginsburg, the most prominent of Boston’s early rock radio DJs, was an ardent promoter of Connor. In the film, musicians, friends, and law enforcement officers all agree that Connor threw away the potential of being a major rock star due to his life in crime.

Asked why he couldn’t get his best friend of many decade to stick to music, Dotoli, who went on to a successful career in concert production, explains that on a good night, Connor would only earn $300 for playing multiple sets. “These mobsters would come over and pull him aside and tell him how to make fifteen grand, so my $300 was always up against the fifteen grand,” he says, adding that Connor, the son of a police officer, was introduced to Boston’s underworld when the band played Revere’s mob-run club circuit.

“It was the attractiveness of making a lot of money, and then there’s getting ‘You’re the only guy I could trust, just drive the car,’” says Connor.

Trying to document Connor’s early music career “was like trying to profile a ghost,” says Macomber. “There’s a 20 second clip on him on stage, a few photos, and a few vinyl signs.” Both the rock and the crime scenes are reenacted in the film. Connor only cut a handful of 45s on tiny labels, but another early Boston rock’n roller, Brehon Herlihy, unearthed a beautiful doo-wop ballad he made with Connor called “Written in the Stars.”

During the periods where Connor was out of jail he would return to the stage, sometimes arriving via a coffin. “He’d be unavailable for six or seven years, and then when he was out there would be all of this press and all of these people who’d want to see him.” The band wasn’t shy about playing up Connor’s notoriety. “Jailhouse Rock” and “Folsom Prison Blues” were on the setlist. Connor would sing “The Ballad of Thunder Road,” from a Robert Mitchum film, and insert a new lyric about stealing a Rembrandt.

“I initially wanted to portray him as a Robin Hood character, but the story got a little more complex,” says Macomber. Still, with such a polarizing figure as Connor, there’s inevitably pushback. “Myles has his proponents and his enemies,” Macomber says. When the film was on the festival circuit some reviews complained that it glamorized an unsavory figure. “We got blistered critically,” laughs Macomber. “They said something like ‘a ludicrous fanzine of a horrible man.’” When Macomber tried having a Facebook page to collect remembrances of Connor from his fans and friends, he got complaints from the relatives of Susan Webster and Karen Spinney. Connor was initially convicted of their brutal 1975 murder, but ultimately exonerated after testimony from blues legend James Cotton that he’d been gigging with Connor on the day of their killing. Still, Macomber says “At that point storytelling be damned, these are people with a raw wound from something horrible that happened.”

The film ends with Dotoli offering his theory about who committed the Gardner theft: underworld figures whose blunders mean that the art is unlikely to return to the museum’s walls. Today Connor, whose last brush with the law was over a decade ago, is 81 and spends his time buying and selling Japanese swords. A series of heart attacks ended his performing career. But for Macomber, he’s still “the ultimate rock ‘n’ roll rebel. Some acts say ‘F you’ on stage, but he said it in a bank vault.’”

“Rock ‘n Roll Outlaw: The Ballad of Myles Connor” screens at the Regent Theatre in Arlington on Sunday, March 17 at 2 p.m.