Advertisement

Field Guide to Boston

A look at the 1924 Boston Marathon, 100 years since the starting line moved to Hopkinton

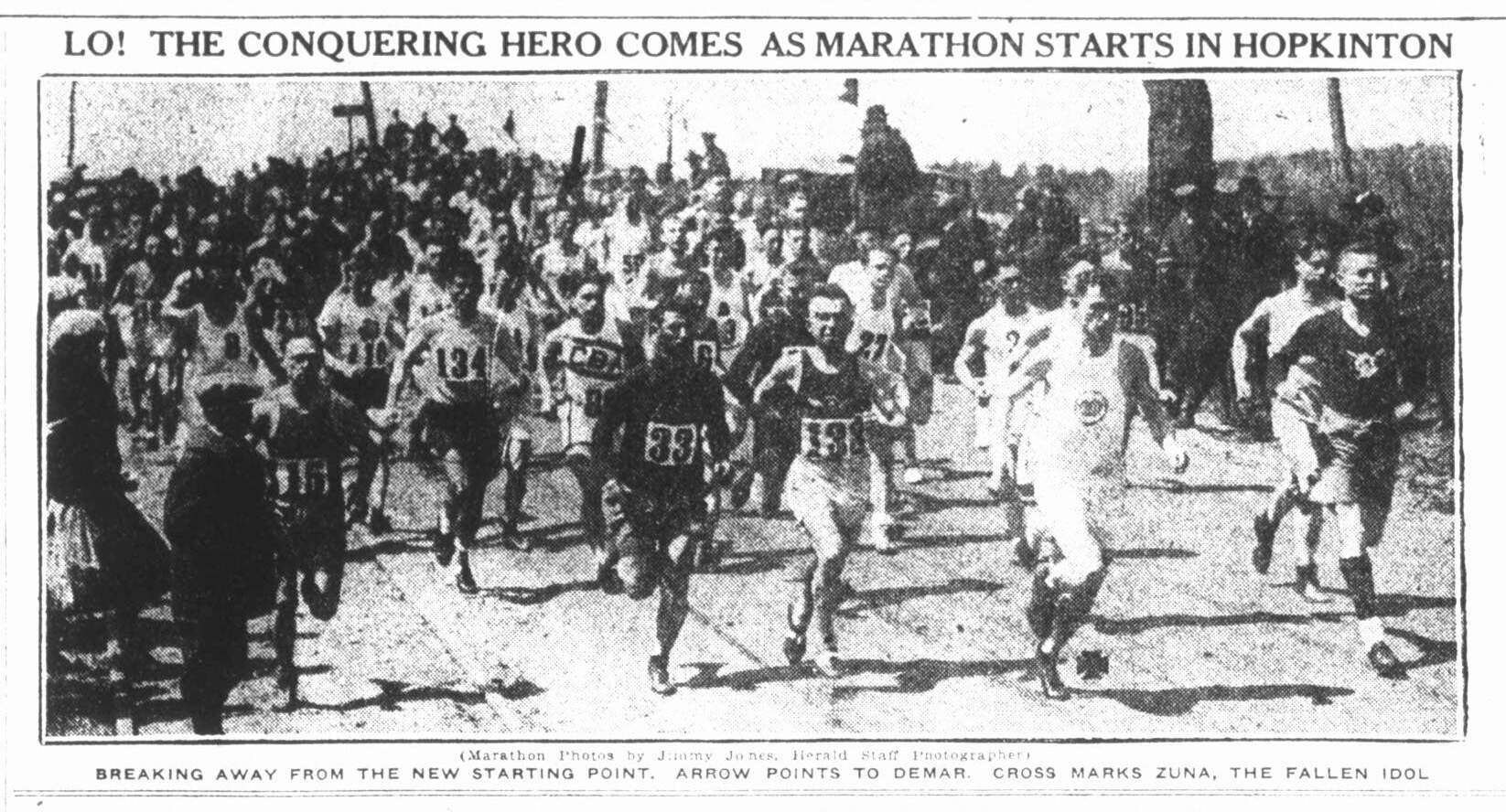

In 1924, the Boston Marathon officials moved the starting line of the race from Ashland to Hopkinton. This year’s race marks 100 years since the marathon was pushed back and lengthened to its full 26.2-mile distance. Here’s a look at what caused the change and what the race was like a century ago.

Why the change

When the Boston Marathon started in 1897, standard marathon length was 24.8 miles. The distance was based on a legend where Greek foot-soldier Pheidippides ran from Marathon to Athens to announce a victory over the Persian army, according to the Boston Athletic Association website. The 24.8 miles put the starting line in Ashland for the first 27 years of the Boston Marathon.

Ahead of the change, Boston Herald reporter Tom McCabe wrote, “One can truthfully say the roads from Ashland to Boston have no rival. The Newton and Wellesley Hills resemble the road Pheidippides traveled.”

But at the 1908 Olympic games in London, King Edward VII and Queen Alexandria wanted the marathon to start at Windsor Castle. The distance from the castle to the Olympic stadium was 26 miles, and an extra 385 yards was tacked on so that runners could wrap up with a lap around a track and end in front of the arena's royal viewing box.

Because of that royal request, Olympic marathon standards increased to 26.2 miles. The B.A.A hadn't made the change after the 1908 games, but the 1924 race was the last test for hopefuls trying to make the American marathon team for the Olympics in Paris that year, according to an article in the Boston Herald. As a result, the B.A.A pushed the route back into Hopkinton to match the Olympic route.

As for how runners were able to meet the new lengthened course, Boston Herald reporter McCabe wrote, "the nine minutes they used up covering the extra distance of almost two miles from the new start to the old point in Ashland is proof that they knew their business.”

The 1924 winner

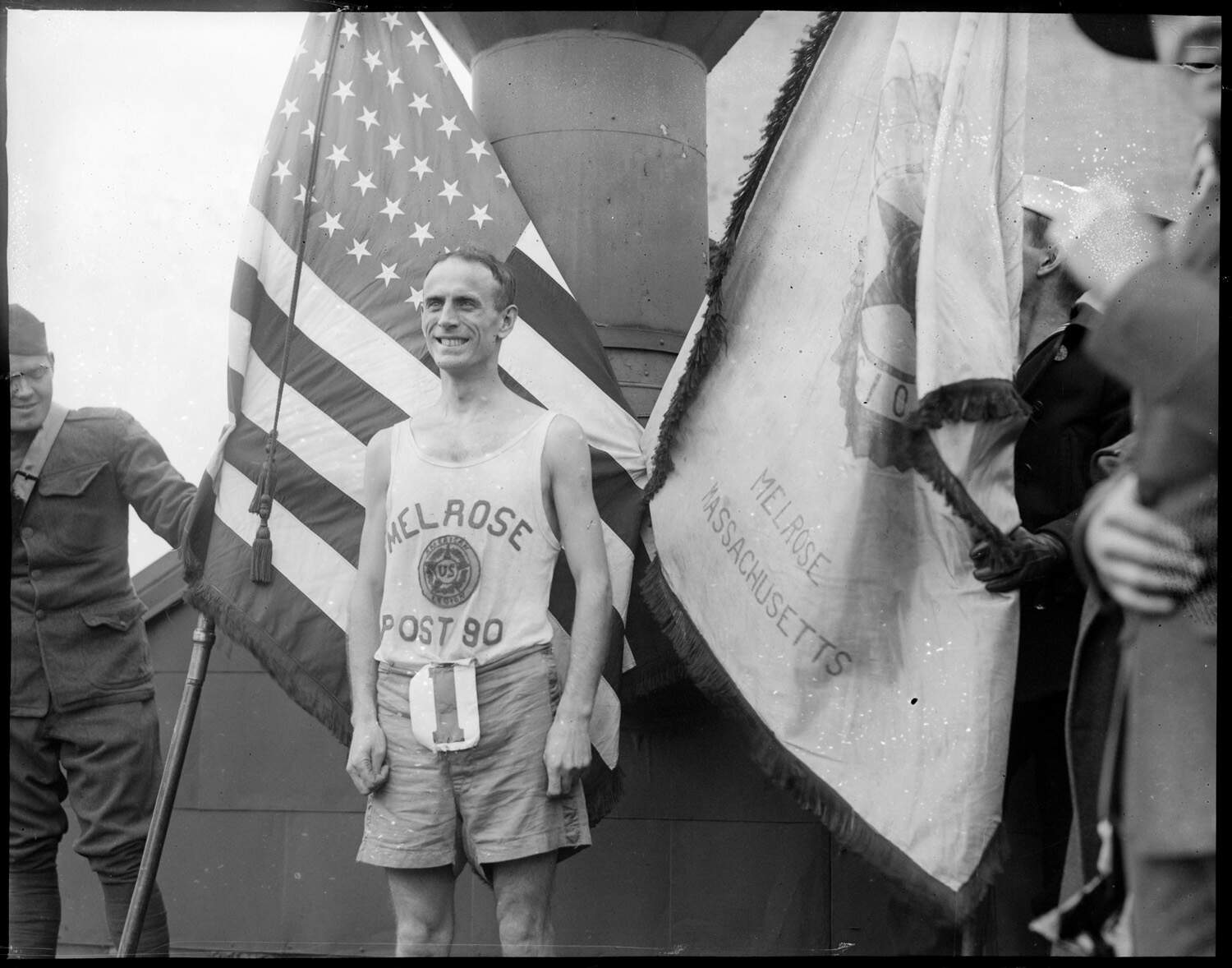

The Boston Marathon, then known as the American Marathon, had 111 racers in 1924. Out of all the runners who attempted the new, longer race, Clarence DeMar came out on top. DeMar (whose name is also spelled ‘De Mar’ in some archival articles) lived in Melrose and was typesetter by trade.

To fuel up ahead of race day in 1924, DeMar ate six eggs he collected from his pet hens, according to Associated Press coverage of his win published in the New York Times. He reportedly ate three eggs before the race, and “The other three he took with him to Hopkinton and ate them after the start of the race. That was his only nourishment for the long grind.”

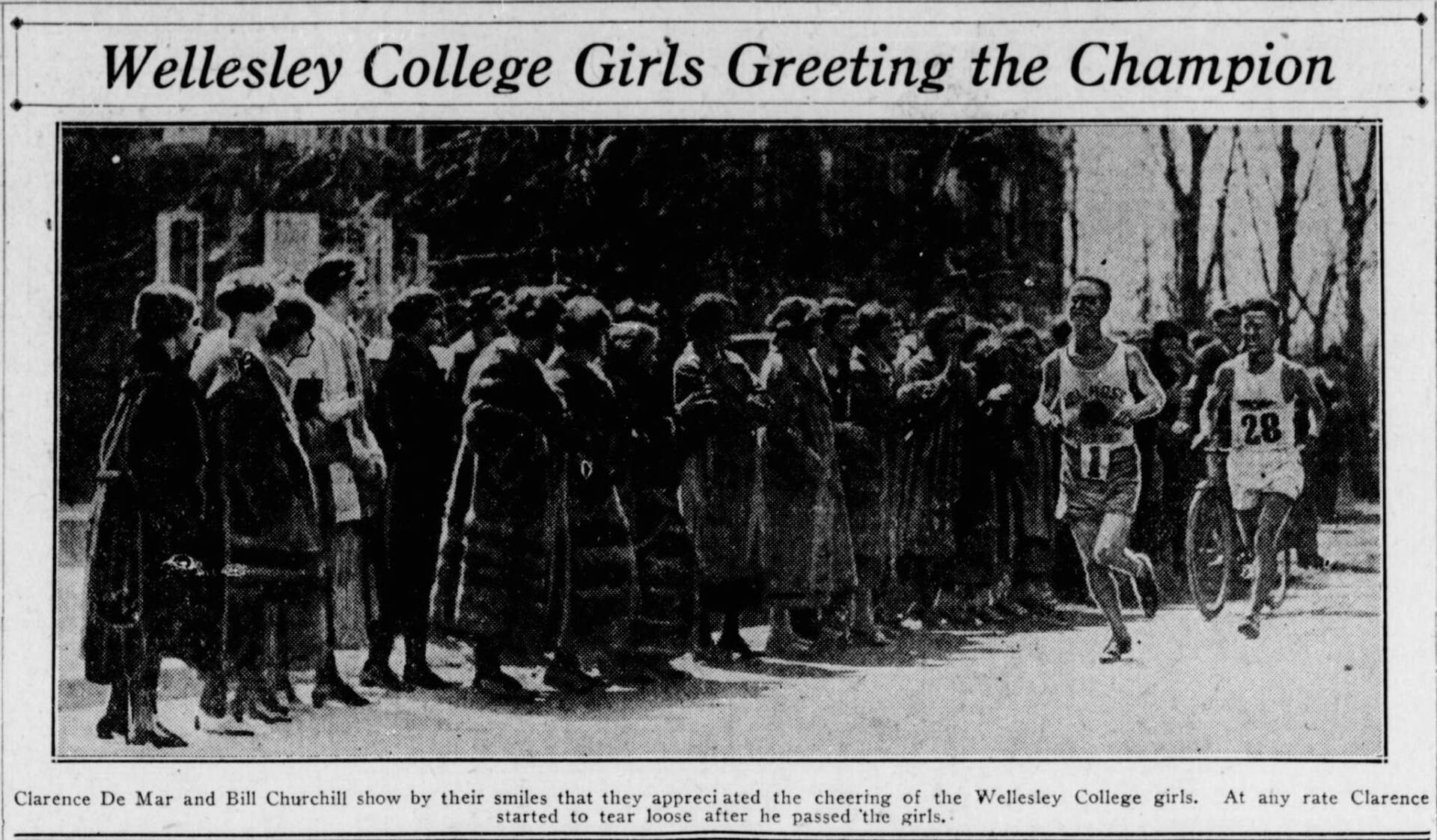

Aside from "a few blisters on his feet," DeMar felt strong, finishing the race five minutes before his closest competitor.

Melrose, DeMar's hometown, was thrilled by his win. When word of DeMar's victory came over the radio, Mayor Paul H. Provandie ordered a fire alarm to ring across the city to alert residents of the win, according to New York Times archives. When DeMar got to Melrose City Hall later that day, more than 2,000 people lined up to shake his hand. DeMar said the hand-shaking “took just as much energy as winning the afternoon race,” according to Boston Herald archives from the Boston Public Library.

The win was DeMar’s fourth in the Boston Marathon, and he went on to win seven in all. DeMar is the winningest Men's Open Division runner of all time. He also competed in the 1924 Paris Olympics based on his performance in Boston and ended up taking home the bronze medal.

Even by his fourth win in Boston, reporters felt DeMar, who they sometimes called "Mr. DeMarathon," was destined for the history books.

“When the history of the Marathon running is written for the future generations, the name of Clarence H. DeMar … will be emblazoned on its pages as the greatest of all men who have sought honors as a long-distance plodder,” wrote John J. Hallahan in the Boston Globe April 20, 1924.