Advertisement

R.I. is using a new app to help people stay off drugs. But is it reaching those most in need?

They are college-educated professionals who own a three-story Victorian home in Providence, drive a BMW and regularly work out at a gym.

Dominic and his fiancé, Samantha, are also struggling with drug addiction. (They asked that only his middle name and her first name be used because their employers don’t know they’re in drug treatment.)

“I actually tried to get clean, three, four times,’’ Dominic, a veteran of Afghanistan, said. “And it was worse than getting shot and catching on fire. It’s horrible.”

He eventually got on methadone, a medication approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat opioid addiction. But there’s no FDA-approved medication to treat addiction to stimulants like cocaine and methamphetamines.

Now, Dominic and Samantha are getting help from a smartphone app that pays them to stay off drugs.

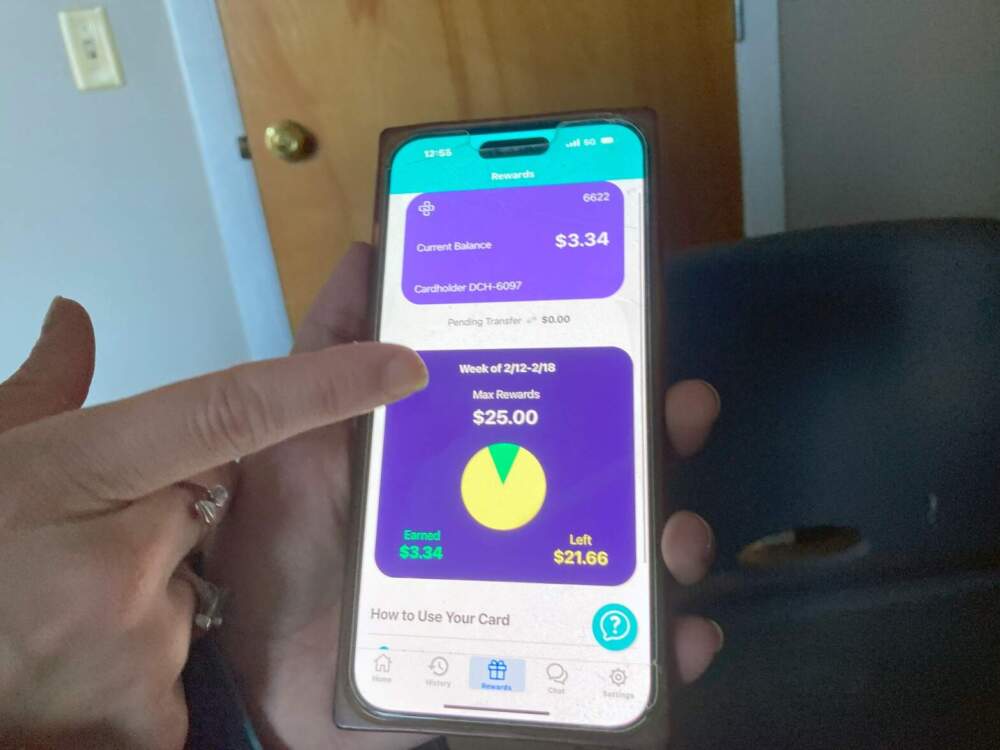

The app lets them earn cash rewards — typically a few dollars at a time — for keeping clinic appointments, completing self-guided lessons on avoiding triggers, and recording saliva-based drug tests.

“It’s the capitalist mind frame’’ said Dominic, 39, a construction superintendent who carries two cell phones. “My time is worth money.’’

His fiancé, Samantha, 30, a marketing account manager, says it’s about more than money. “It’s just the fact of doing that accomplishment and saying, ‘Okay, I can actually do this,’’’ she said. “And when you’re coming out of a dark place, having those little accomplishments build you up.’’

The app developed by a Boston-based tech company uses a type of motivational intervention called contingency management, because rewards are contingent on abstinence.

DynamiCare Health’s app is being piloted at CODAC Behavioral Healthcare, where Dominic and Samantha are patients. CODAC is one of one of four Rhode Island opioid treatment programs using the app primarily for people on methadone who have a “secondary stimulant use disorder,” said Linda Mahoney, administrator for substance abuse services at the state Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals (BHDDH).

“Instead of people chasing the drug, they’re now chasing the reward,’’ Mahoney said. “And the reward is recovery.”

Rhode Island purchased the app with about $500,000 of the $50.8 million that have flowed into state coffers so far from legal settlements with companies accused of flooding communities with opioid painkillers.

But while DynamiCare’s program appears promising, experts say, its accessibility and effectiveness is still not known. And some of the state’s own advisors say Rhode Island’s program is not reaching the people most in need of help.

“Ninety-nine percent of the research [on motivational incentives] has been done…with human beings interacting with other human beings,’’ said Richard A. Rawson, a research professor at the University of Vermont, where the motivational intervention known as contingency management was pioneered in the 1990s. “Because all 19-year-olds know how to use apps,’’ he said, “doesn’t necessarily mean that people who are 50, who have lived on the street for the last 10 years, if you put a app in their Obama phone, whether they’re going to be able to use it.’’

Rhode Island’s decision to pilot the DynamiCare program at four state-licensed opioid treatment programs, also is “very off-target,’’ said Dennis Bailer, a former co-chair of the state Opioid Settlement Advisory Committee’s racial equity working group.

Most of the Black and Hispanic people in Rhode Island who are dying of accidental overdoses have never received methadone or buprenorphine, medications used to treat people with opioid addiction, according to a 2020 study by the Rhode Island Department of Health. Methadone is only administered in opioid treatment programs. And enrollment in the state’s methadone treatment programs is far lower among Black and Latino people than among White people, according to preventoverdoseri.org.

‘’We need to do something that’s going to really reach the people of color,’’ Bailer said, “who are primarily stimulant users who are overdosing because of fentanyl in their crack cocaine, in their crystal meth.’’

Stimulant users at higher risk

Nationwide, the combination of cocaine and meth with fentanyl — a synthetic opioid 50 times more powerful than heroin — is driving what experts call the “fourth wave” of the opioid epidemic. Rhode Island had the country’s fourth-highest rate of overdose deaths involving cocaine in 2022, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

People who regularly use cocaine or meth but not opioids generally have a lower tolerance for fentanyl, which puts them at even higher risk of dying of an accidental overdose.

Now, as opioid settlements pump billions of dollars into states across the country, contingency management is among the evidence-based interventions that experts and advocates say could help address the rising overdose death rates among people who use stimulants like cocaine and meth.

But in Rhode Island, people addicted to stimulants who are not in treatment for opioid addiction don’t have access to the app.

They’re people like Tyler, a 35-year-old waiter from Boston who is addicted to meth. (We’re using only his middle name because he uses illegal drugs.)

In 2020, Tyler said, he was in recovery and he’d just moved in with his boyfriend. Then the pandemic hit and Tyler relapsed. “I was an alcoholic and I was a cocaine user,’’ he said. “And when COVID hit, my recovery wasn’t strong enough.”

Tyler couldn’t get back into rehab because of the lockdown. His relationship failed. Then someone he met offered him “Tina,’’ a street name for meth. A highly addictive stimulant, meth is especially dangerous for people like Tyler, who said he has bipolar disorder and schizoaffective disorder. Tyler said he began hearing voices. He stopped eating. He didn’t leave the house. Eventually, he landed in a hospital psychiatric ward.

Tyler was living on the streets when he found help at Project Weber/RENEW, a peer-led harm reduction and recovery group in Providence. He managed to remain abstinent for the required 30 days to get into a recovery house. So far, Tyler said, he’s been off meth for two months. But he still struggles.

Tyler said that getting paid to stay sober sounded “too good to be true.”

But someone like Tyler would not have qualified for the DynamiCare pilot because he isn’t enrolled in an opioid treatment program.

Paying people to stay off drugs

Offering people struggling with addiction small rewards, like gift cards or vouchers, to make positive changes is rooted in the theories of behavioral conditioning that date back to psychologist B.F Skinner. The motivational intervention works by triggering the same instant gratification response in the brain that people get from using drugs or alcohol. Its effectiveness has been documented in a decade of National Institutes of Health-funded research studies, including randomized controlled trials, the gold standard of medical research.

The country’s second-largest health system, the Veterans Health Administration, has used contingency management administered by trained staff for more than a decade to treat substance use disorders.

But contingency management isn’t widely used in community-based treatment. Except for pilot programs, private and public insurers generally have been unwilling to reimburse providers for contingency management. A major barrier are federal and state regulations suggesting that government-funded health programs that provide financial incentives may trigger anti-kickback laws.

The resistance began to shift in 2021 when the Biden Administration announced plans to expand access to evidence-based treatment for opioid addiction, including contingency management. Experts in motivational incentives published recommendations for how to use the incentive-based treatment without violating federal law.

A private company founded in 2016, DynamiCare rode a wave of venture capital funding during the pandemic for remote health treatments. DynamiCare’s investors include Rhode Island’s former U.S. Rep. Patrick J. Kennedy, a leading advocate for mental health and addiction care who Politico described as the “go-to player” for companies with a stake in the multibillion-dollar response to the opioid crisis.

In Rhode Island, Mahoney, the BHDDH administrator, said that she first learned about DynamiCare’s app in 2022, after the company received a favorable advisory opinion from the federal Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Inspector General. The office concluded that DynamiCare’s smartphone and debit card technology would not trigger the anti-kickback statute. The advisory opinion “really helped” reassure state administrators, Mahoney said, that DynamiCare was following the rules.

DynamiCare’s technology blocks the use of its gift cards at liquor stores or for cash withdrawals. The smartphone app also has GPS that can track users’ attendance at appointments. The app was especially appealing, Mahoney said, at a time when treatment programs are short-staffed. “It just seemed like a really, really good fit,’’ she said.

In April 2023, the state signed a 12-month $389,815 no-bid contract with DynamiCare. At the time, the contract said, there was only one other vendor, Pear Therapeutics, that offered an app-based program. (Pear has since gone out of business.) But other digital health companies such as Affect Therapeutics, Chess Health and Q2i also now provide app-based addiction treatment.

In addition to the $500,000 in opioid settlement funds, the state used another $99,935 from a State Opioid Response grant from the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to pay DynamiCare. The grant also included federal anti-kickback language which, Mahoney said, prevented the state from offering the app to people not already enrolled in the opioid treatment programs. Otherwise, she said, the state might be seen as using the app’s monetary rewards to recruit people into the program.

“The intent of the language,” a SAMHSA official said in an email, “is to ensure contingency management is used in an appropriate clinical capacity as a therapeutic intervention and not as a recruitment tool.” The agency “does not restrict the use of SOR funds for contingency management to opioid treatment programs.”

There also were practical considerations. Rhode Island couldn’t “directly pay every provider to use contingency management,” Mahoney said in an email, “only those that we could prove were trained to fidelity.” The opioid treatment programs provided a “strong base of staff that were already trained,” she said, to ensure the grant requirements were met.

But while DynamiCare’s program “seemed to have some benefit for patients already attending a substance use treatment program,” the effectiveness of delivering contingency management through its smartphone app has not been tested in any randomized controlled trials, said Dr. Andrew J. Saxon, an addiction psychiatrist who has researched the subject at the University of Washington School of Medicine. All of the major research on contingency management, Saxon said, has been conducted on programs administered in-person, not using an app.

And even if the DynamiCare app had been offered to people outside of opioid treatment programs who are addicted to stimulants, Bailer of the state Opioid Settlement Advisory Committee and others said, it’s unclear how useful it would be for more marginalized populations.

“I know our clients lose their phones a lot,” said Lisa Peterson, chief operating officer of VICTA, an outpatient treatment program in Providence. And the app is not practical, she said, for people with addiction who live in tents. “There’s no wifi in the encampments.”

‘Not as good as we’d like to see’

Even getting patients in the opioid treatment programs to use the app proved challenging.

The state enrolled five treatment sites in Providence, Pawtucket and Woonsocket in the DynamiCare program. The clinics were chosen, Mahoney said, based on those serving areas with the highest rates of overdoses and the largest number of Black and Hispanic clients.

But despite the state’s effort to target clinics with more diverse populations, 51 of the 67 patients in the pilot who completed a demographic survey — 76% — were White, according to the state BHDDH. The numbers of Black and Hispanic participants — 5 and 8 respectively — were too small, researchers said, to draw any conclusions about how well the technology worked for patients in those groups. Just over half of the patients in the pilot were “living in unstable housing,” which the BHDDH defined as either unsheltered or at risk of being homeless.

During the first 12 months of the pilot, the agency said, 60% of the 119 patients enrolled in the program — 72 people — made it to the intervention stage, meaning they actually used the app to help manage their drug use.

But most of the patients who tried the app didn’t stick with it. After 12 months, more than half the patients had stopped using the app.

The low numbers didn’t surprise Mahoney, the BHDDH administrator. “It’s a pilot program,” she said, and they’re still working out the kinks. And “this is a tough population,” she said. “They don’t want to die, but they want to continue to use. So when you start doing a mouth swab that says they’ve been drinking or they’re doing cocaine and they want to continue to do that, they’ll back off from going anywhere further.”

Dr. David R. Gastfriend, an addiction psychiatrist and DynamiCare’s co-founder and chief medical officer, said that Rhode Island’s numbers were “not as good as we’d like to see.” But he said the patients in the program were sicker than those in its other pilots.

“These patients have to come in every day to get a pill, or a dose of methadone,’’ Gastfriend said, “so they’re much sicker. So the numbers are worse.”

Rhode Island is not the only pilot program where patients had trouble using DynamiCare’s app.

Saxon, the addiction psychiatrist at the University of Washington School of Medicine, was among the researchers who conducted a 2022 pilot study on DynamiCare’s smartphone app for patients addicted to meth.

“Our results were not what we were hoping for,” Saxon said. “Essentially, what we found was that using the app was pretty complicated. There were a lot of steps to go through. And many of the study participants really couldn’t get through the initial steps in order to use the app to do the contingency management.”

Just over half the number of people who consented to participate in the study, he said, were able to get to the point of using the app for rewarding positive behavior.

“Some of the struggles that the participants had in using the app may have to do with their level of really severe impairment,’’ Saxon said, “although that population is not unusual among people who are using methamphetamine.’’

DynamiCare’s Gastfriend said that the company is working diligently to better understand the barriers to using the app and how to reach diverse populations. Among other things, he said, the company is hiring a team of Spanish-speaking staff.

“We’re trying to figure out, you know, basic things like, is the reading comprehension level doable for people who don’t have high school diplomas?” Gastfriend said. “Is the level of conversation on these video, telehealth visits, focused on what the patient’s life is like, and what they’re going through — their trauma, background, their comprehension and… their culture?”

Motivational incentives without an app

Other states, meanwhile, are finding ways to provide contingency management in-person.

In Oregon, peer recovery coaches at community-based organizations are being trained in contingency management to help people who use stimulants, primarily meth. About two thirds of the 1,280 participants in the Oregon study are homeless; none of them were in treatment when they joined the program, said Dr. Todd P. Korthuis, the study’s principal investigator.

California last year became the first state in the nation to receive a federal waiver to use in-person contingency management in its Medicaid program.

Rhode Island also has applied for a Medicaid waiver to fund another contingency management pilot. In its application, the state said it wants to target people with stimulant use disorders, saying that “rising cocaine use is a significant health equity issue for Rhode Island.”

On April 1, the state signed a six-month renewal of its contract with DynamiCare. The $201,189 contract runs until Sept. 29, 2024.

Mahoney, of BHDDH, said that she’s confident that the state is going in the right direction, but said the agency is going to “keep an eye on this.”

The state Opioid Settlement Advisory Committee has allocated another $1.3 million in settlement funds to expand treatment for people who use stimulants, according to a spokeswoman for the state Executive Office of Health and Human Services. No decisions have been made yet on how that money will be spent.

The Public’s Radio in Rhode Island and WBUR have a partnership in which the news organizations collaborate and share stories. This story was originally published by The Public's Radio.