Advertisement

Mother-daughter duo preserves — and exhibits — endangered Jewish films

The National Center for Jewish Film in Waltham can be tricky to find. But inside the nondescript concrete building, tucked along the northern edge of Brandeis University’s campus, floor-to-ceiling shelves hold part of the largest collection of Yiddish language and Jewish-related films in the world.

“It may look like a lot,” says the center’s co-founder, Sharon Pucker Rivo, gesturing to shelves full of 16mm film canisters. “But we also have a lot in cold storage in Maine.”

Pucker Rivo began collecting, preserving, restoring, then distributing and exhibiting films related to the Jewish experience in 1976, when Brandeis granted her the space the center still uses to this day. In 2006, her daughter Lisa Rivo joined the fold and together they have shouldered the joint mission — and responsibility — of fostering the analog artifacts of a global cinematic history that otherwise would not have survived.

“It's a huge job,” acknowledges Pucker Rivo, now 84. “But to me, it's like a treasure hunt.”

Not fully retired, Pucker Rivo says her daughter does a lot of the center’s “heavy lifting.” (At one point during our interview, her daughter, 54, discourages her from lifting a box from the floor.) “I kind of get the funner things to do,” she smiles. Like watching 40 films to help determine the lineup for the center’s annual Boston film festival, which takes place at the Coolidge Corner Theatre from May 12-21.

The center has exhibited films on and off since its earliest days. At any given point, films it distributes could be screening at theaters or festivals all over the world. But the Boston festival, which can include picks from their own archive as well as other repertory and contemporary titles, started in earnest about 30 years ago.

“Here’s ‘Mothers of Today,’ the 35mm print,” says Lisa Rivo, placing her hand on a worn box that could fit a couple of pairs of large shoes. Out of an abundance of caution, she plans to drive it over to the Coolidge herself. “Then it will go to Toronto. It's in great shape,” she says.

Fitting in so many ways, “Mothers of Today” kicks off the festival on Mother’s Day (May 12 at 1 p.m.). Rivo calls the “over-the-top” 1939 Yiddish melodrama an example of the shund genre, “a Yiddish word sometimes described as trash or, as opposed to high art, low art.” Pictures in that proudly low-brow category were beloved by the 1930s Jewish working class, often for the depictions of their lives on the big screen, she explains.

In this case, two New York families with headstrong mothers find themselves at odds. One family abides tradition, one bucks it — and the law. Characters break into song, including the “traditional” mom played by radio personality Esther Field, in one of only two appearances on film. Even those unfamiliar with Yiddish will notice, and likely appreciate, the unique swapping of English and Yiddish words as an experience common among multilingual immigrants.

For all of those reasons and more, the center invested in the restoration of “Mothers of Today” as it has with nearly 50 other Yiddish features. (Film deteriorates over time; the Library of Congress states that fewer than 20% of all silent films made and less than half of all American films made before 1950 survive.) This screening marks the New England premiere of the restoration as well as the film’s 85th anniversary.

Even though the center has restored hundreds of other films, Yiddish titles hold particular significance to Pucker Rivo, who associates the endangered language with her grandmother, whom she lived with as a child. Plus, she notes that the films, made from about the 1910s through the 1940s in pockets around the world, almost immediately became obsolete because “they’re being made for an audience that no longer exists, primarily because they were killed.”

“Very quickly you have films that are already relics, in a way,” she adds.

Though neither restored nor distributed by the center, yet wildly popular among cinephiles, Michael Roemer’s “The Plot Against Harry” from 1969 also screens in a new 4K restoration (May 15 at 7 p.m.). The deadpan comedy about a put-upon crook didn’t gain traction among distributors so Roemer shelved it until 1990. Harvard Film Archive hosted a Roemer retrospective in 2022 and now houses a 35mm print. Thomas Doherty, a Brandeis professor who Rivo calls “one of the world's great film historians,” will speak after the screening.

Brandeis professor Laura Jockusch is working on a book about Gestapo informant and jazz singer Stella Goldschlag and will speak after the fictional movie inspired by Goldschlag, “Stella. A Life,” (May 19 at 11 a.m.). Jockusch will also speak after the murder mystery documentary “Revenge: Our Dad the Nazi Killer” (May 19 at 2:30 p.m.).

Four other films screen this year, a mix of contemporary fiction and nonfiction, including another mother-daughter story in “Seven Blessings,” by director Ayelet Menahemi. Her feature “Noodle” opened the center’s 2008 festival. Set over a seven-day, cross-cultural wedding celebration, two real-life cousins (Reymonde Amsallem and Eleanor Sela) co-wrote the “Seven Blessings” script and play sisters on screen.

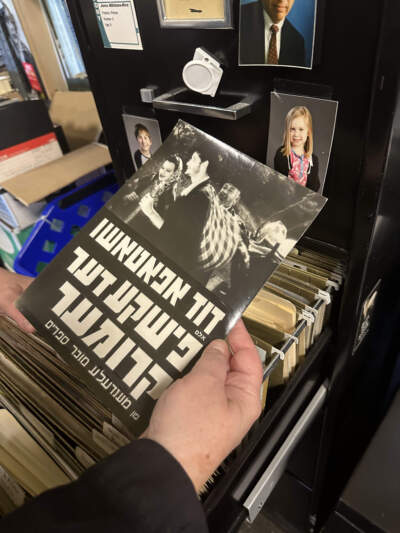

Returning to the materials that surround them, Pucker Rivo and Rivo take turns pointing out one gem after another. “Tevye,” the 1939 precursor to “Fiddler on the Roof,” Yiddish film scripts, home movies from North Africa, clips of neighborhoods leveled by war, original promotional stills and negatives, the list goes on. Rivo also acknowledges the omissions, whether people had few resources or were under threat. “There's a lot that we don't have because it wasn't filmed,” she says.

When asked about added security given public responses to the Israel-Hamas war, Rivo says the center has consulted with law enforcement and other Jewish agencies. “We’re prepared but we’re not concerned,” she says, adding that none of the titles directly refer to war or this specific conflict. For her, the festival puts forth “works of artistic excellence with nuanced conversation… that’s what we’re focused on.”

Looking ahead, Pucker Rivo says she’d like to spend more time with the home movies, maybe start organizing and cataloging some boxes in cold storage. “Every reel that we save, we've made a little bit of a contribution,” she says.

“I call it my album of the Jewish people.”

The shelves may look full already, but with this mother and daughter, there’s always room for more.

The National Center for Jewish Film's annual festival runs May 12-21 at Coolidge Corner Theatre.