Advertisement

A Raymond Chandler Mystery Provides A Baseball History Lesson

Resume

This story originally aired on Oct. 19, 2013.

Raymond Chandler produced a string of novels and short stories, many featuring legendary private detective Philip Marlowe. Chandler wrote fiction, but one of his works offers a brief glimpse into a real, but bygone era of baseball.

The hard-boiled hardball history lesson appears in Chandler's novel "The High Window." Marlowe is after a rare coin known as the Brasher Doubloon. The plot does more twisting than Chubby Checker. When Marlowe pays a visit to another detective, he notices a Dodgers game is on the radio in the apartment across the hall. Marlowe describes the scene:

I knocked, got no answer and knocked louder. Behind my back three Dodgers struck out against a welter of synthetic crowd noise.

Hang on. “Synthetic crowd noise” sounds fishy. Plus, the book is set in Pasadena and Los Angeles. "The High Window" was published in 1942. That’s 16 years before the Brooklyn Dodgers migrated west to California. Yet, Chandler chose to mention them.

He gives us a clue as to why when he mentions that the broadcast is a “recreated ball game.” Not a replay, but a recreation.

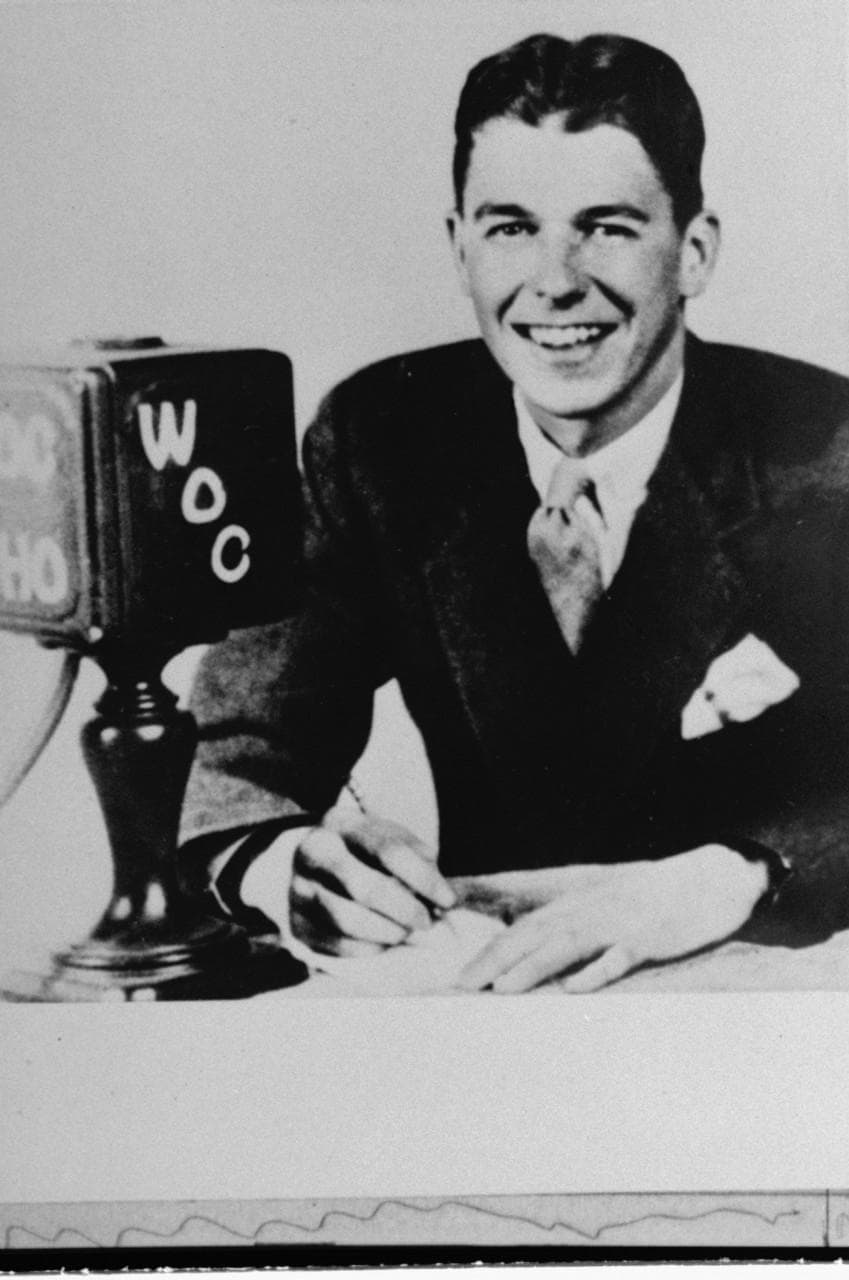

From the 1920s well into the 1950s, radio stations started recreating games for same-day, delayed broadcasts. In the 1930s, Ronald Reagan worked as a radio sportscaster. The future actor, governor and president recreated Chicago Cubs games for WHO in Des Moines, Iowa.

Jim Williams worked on dozens minor league baseball recreations for KVVC in Ventura, Calif. in 1951 and ‘52.

“It was very expensive to rent telephone lines for several hundred miles. And to also send sportscasters from, say, Ventura to Modesto,” Williams told Only A Game.

Ventura had a team in the California League. Williams, now 81, was just beginning a long radio career when he served as the sound engineer for recreated road games.

“We had a telegrapher from the Western Union office who we hired who came to the radio station in Ventura," Willams said. "His counterpart would be at the stadium in Modesto, and then he would type out a few dots and dashes and send a brief message to our telegrapher.”

One half inning at a time, the telegrapher would type up the action, and there weren't too many details. Williams gave an example:

Modesto at bat. Smith strike one low. Ball two. Hit to centerfield. Caught by Sam Jones.

The announcer in Ventura would then call the game, adding color with statistics and other details. Williams would play sound effects records to round out the production:

“Booing, crowds cheering, people running around selling popcorn," he said. "‘Get your fresh popcorn here! Get your red hots here! Get your Coke here!’”

And there was a wooden bat hanging near the announcer’s microphone.

“If there was a hit, he would simply take his wooden ruler and hit the baseball bat extending from the ceiling," Williams said.

For pitches that made it to the catcher, the sportscaster also had a baseball and a glove.

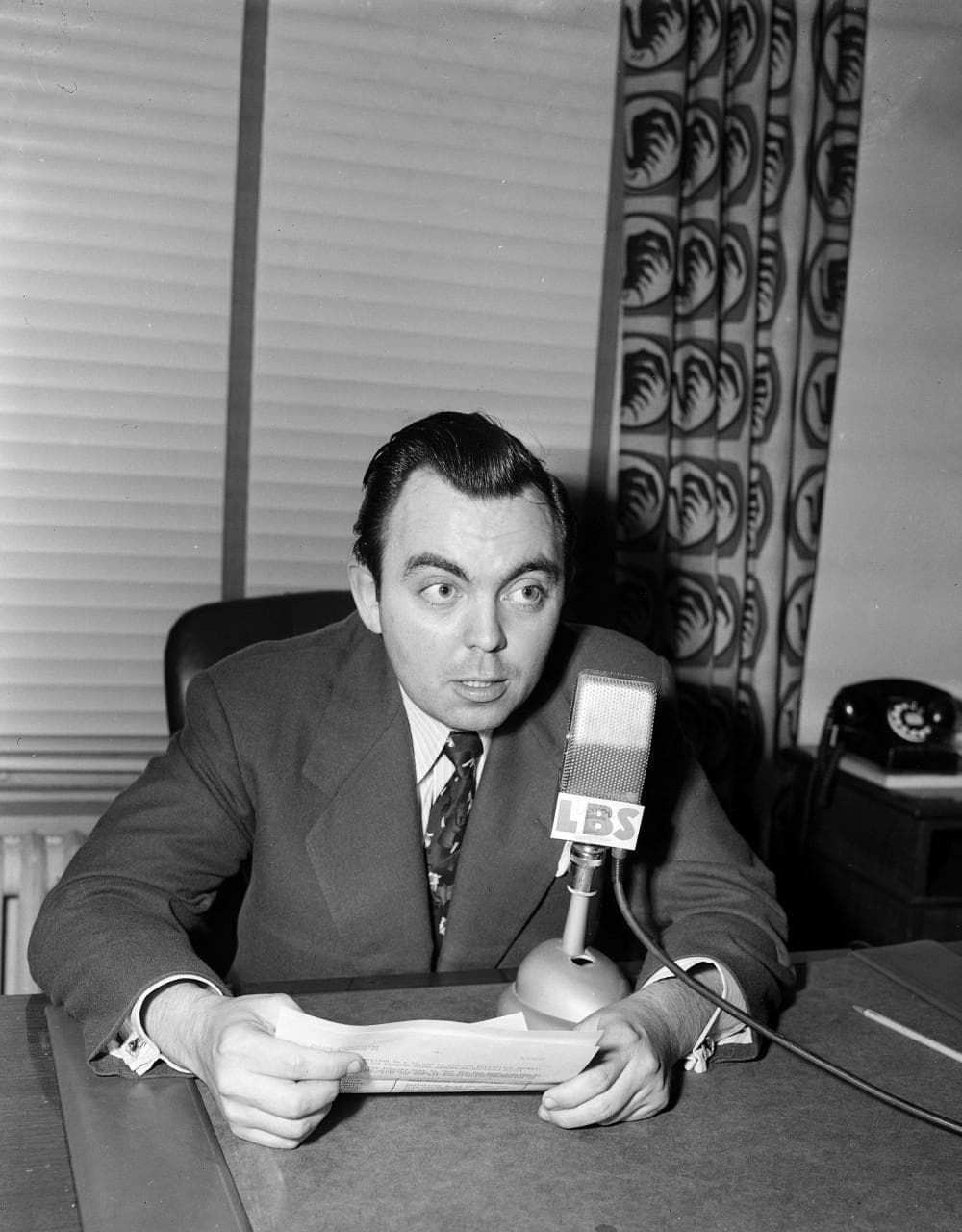

The master of the art form was Gordon McLendon. From 1947 to 1952, McLendon and his Liberty Broadcasting System delivered elaborate major league recreations from his studio in Dallas. At its peak, Liberty had nearly 500 affiliate stations, mainly in the West and South where there were no big-league teams.

Most stations acknowledged the broadcasts were recreations in announcements before and after the games. The biggest concern was a broken telegraph or human error at the ballpark. Williams still remembers the worst breakdown during his work on recreations for KVVC.

“Modesto came to bat. They had an inning, and they had four outs, and they went down. Then they came right back up to bat again. That does not happen in a ballgame,” said Williams, who is now an author and wrote an article about the incident.

The announcer in Ventura started to fill time and eventually announced a fake storm and rain delay while the telegrapher phoned the press box in Modesto.

“Well, when the telegrapher came on the horn, on the telephone, he was drunk,” Williams said.

The staff in Ventura got a newspaper reporter at the stadium to give them a summary over the phone after each half inning.

“Our sportscaster came on and said, ‘Well, the storm is now over. Let’s get back to the game.’ That was a hair-pulling time. It never happened again. And I would assume that the telegrapher in Modesto got fired, too,” Willams said, laughing.

The 1947 film adaptation of "The High Window" was called “The Brasher Doubloon” and starred George Montgomery as Marlowe. The Dodgers recreation is not in the movie, but the book offers one more historically accurate sports tidbit. After Marlowe finds the other private eye dead, a neighbor ties his alibi to the length of the baseball broadcast. And Chandler got it right: his estimate would put a game at about two and half hours – pretty much in line for the era – and significantly shorter than today’s nearly three-hour average.

So, that’s the story of what Raymond Chandler can teach us about baseball history. And I better wrap this up before it turns into a long goodbye.

This segment aired on December 27, 2014.