Advertisement

In New Biography, Former NHL Goalie Malarchuk Details Brushes With Death

ResumeClint Malarchuk caught and deflected pucks from 1985 through 1992 for the Quebec Nordiques, Washington Capitals, and the Buffalo Sabres. He's also coached in both the minors and in the NHL. But most hockey fans know Malarchuk for one especially gruesome incident in 1989, when an opposing player's skate slashed his jugular vein, which required life-saving measures from an athletic trainer.

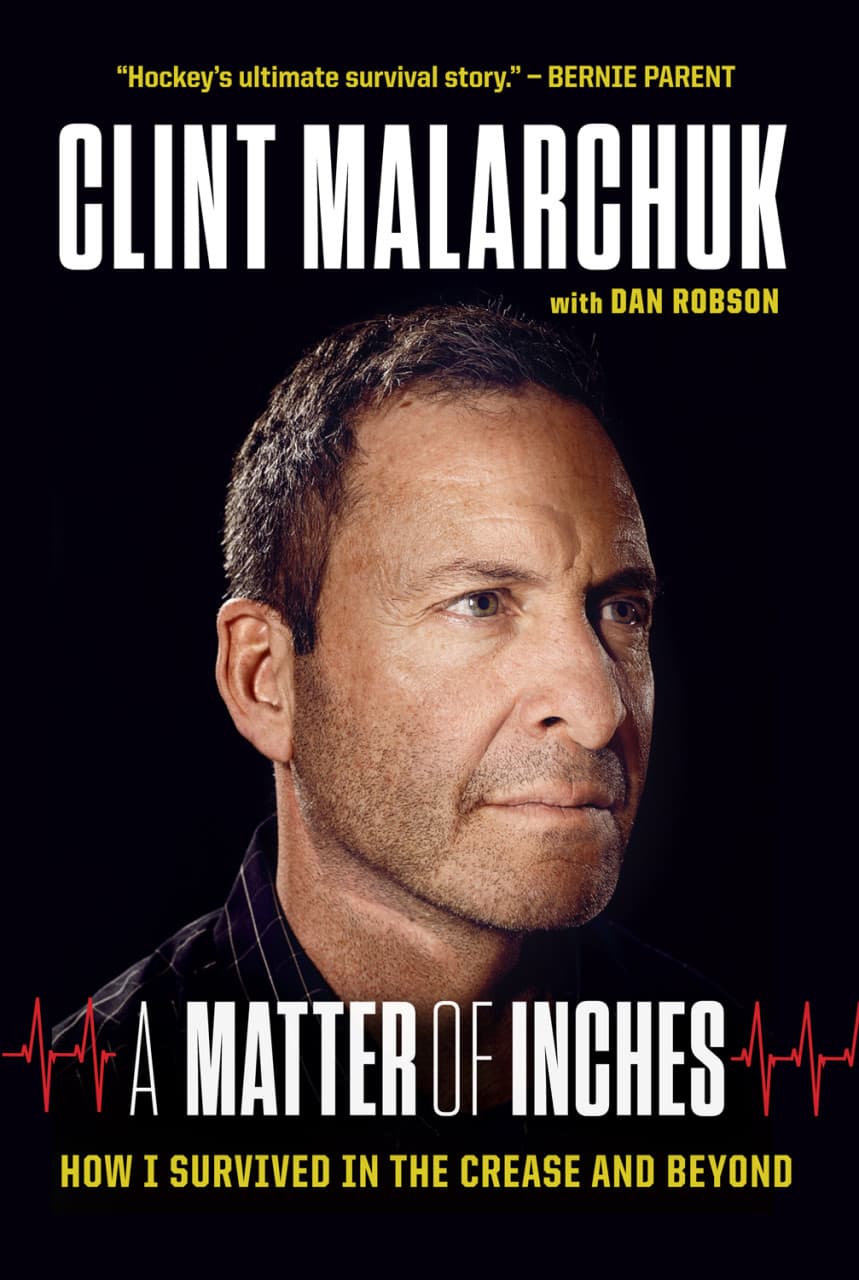

Now, with co-author Dan Robson, Malarchuck has written "A Matter of Inches: How I Survived in the Crease and Beyond" and he joined Bill Littlefield.

Highlights from Bill's interview with Clint Malarchuk

BL: You contend in "A Matter of Inches" as follows: "I basically willed myself into becoming an NHL goalie." Tell us a little about the obstacles you had to overcome by will to get to the NHL.

"I didn't try to act out in any way or [act] superstitious before games or anything like that because it was the OCD I was hiding."

Clint Malarchuk, former NHL goaltender

CM: I didn't feel normal as a kid, let's put it that way. Later on, big anxiety. A lot of anxiety and things like that. And nothing was ever flat-out said that I was diagnosed with a certain disorder or anything like that. But looking back now, as things happened and evolved in my life, I was certainly very much obsessive compulsive, and when I say I willed myself to be an NHL goaltender, I think that the OCD helped me make it to the NHL because of my obsession with training, with being the best that I could be. And it was very over the top. Usually 12-year-olds aren't doing quite that, even if they're aspiring to be an NHL hockey player.

BL: You've been frank about your obsessive behavior and your anxieties since your retirement, and you're certainly candid about them in the book. How did you handle them while you were still playing in the NHL?

CM: Well, especially with goaltenders and superstitions, there's a lot of athletes that are that way and especially goaltenders are kinda quirky, and it almost gives goalies a green light to behave any way they want: "Oh, he's just a goalie," and that's OK.

CM: Well, especially with goaltenders and superstitions, there's a lot of athletes that are that way and especially goaltenders are kinda quirky, and it almost gives goalies a green light to behave any way they want: "Oh, he's just a goalie," and that's OK.People that suffer with obsessive-compulsive disorder, we're great actors because we don't want anybody to know what we're going through and why we're doing certain things, so for me, my biggest thing was hiding all this stuff that was going on with me. So I became a normal, functioning goaltender on the outside. People looking at me go, "Wow, you're the most normal goalie I've ever played with." I didn't try to act out in any way or [act] superstitious before games or anything like that because it was the OCD I was hiding.

BL: The 1989 accident in which your throat was cut by a skate could have ended your life, never mind your career. But apparently you only realized how traumatic that incident had been many, many years after it happened, is that right?

CM: That's bang on. After the accident I did go through a lot of things, but I ended up being diagnosed with OCD then because within that year or two after that accident I really spiraled into a deep depression. The OCD became almost unbearable where it was hard for me to leave the house. Definitely panic and anxiety at times. Once I got on the right medication and things really went good for a number of years, I kind of relapsed into a state of depression. I ended up becoming suicidal and even attempted suicide. And to this day I still have a bullet lodged in my skull.

I was in intensive care. I went to a treatment facility. And they worked on a lot my issues. I was self-medicating with alcohol, so that was one of the issues. A counselor there suggested I may have PTSD because of the accident in 1989. Now this is all happening in 2008, and I wouldn't buy into it. By no means I was accepting the PTSD. I accepted depression, anxiety, OCD, sever anxiety — I didn't need any more initials. But I took the initials PTSD and started to work on that, learning so much about how trauma affects people. And now with our veterans coming back, we have 22 suicides a day by veterans. They survive the war, they come back and commit suicide because of PTSD. And I've heard some of them discuss their anger and their depression and anxiety, and I totally relate to that.

BL: The chapter titled "Lucky One" includes these words: "This book wasn't easy to write. It took me back to a lot of places I never wanted to see again." In fact, you write that you relapsed while the book was in progress. Now that it's out, do you feel that it was worth going back to those places?

CM: Absolutely. People say, "Was it therapeutic to write?" Not a chance. I had done so much therapy and put it all behind me. And I went very deep. The book is described as raw. I wanted to help people, and, unless I had gone to those places that I'd been, it's not going to help people that are living in that place.

And it was a hard project. I quit several times. I didn't want to do it. I always came back and pecked away at it. But the feedback that I'm getting is just so gratifying. ... I thought my purpose was to play in the NHL. And then I thought my purpose was to coach in the NHL. Now I look and those were just stepping stones.

Bill's thoughts on "A Matter of Inches: How I Survived the Crease and Beyond"

Former NHL goal keeper Clint Malarchuk acknowledges that "A Matter of Inches" is no hockey book. Rather it is the story of a man exceptional for surviving not only a gruesome on-ice accident, but assaults over the years from his personal demons, which have included compulsions, obsessions, depression, and addiction. Malarchuk has said that revisiting the night when his throat was sliced open by an opponent's skate was excruciating.

[sidebar title="An Excerpt From 'A Matter of Inches'" width="630" align="right"] Read an excerpt from Clint Malarchuk's "A Matter of Inches: How I Survived in the Crease and Beyond."[/sidebar]In fact, recalling that episode and others was so painful that he quit work on the book a couple of times. Talking about his obsessive-compulsive disorder, his attempted suicide, and the on-again-off-again nature of his recovery from addiction has also been extremely difficult. But his contention that he wants to help others by telling his story is powerful and convincing.

Malarchuk's past has been so painful that it's impossible to encounter him through the book or in conversation without wanting to wish him strength and serenity in the future.

This segment aired on January 10, 2015.