Advertisement

Super Bowl 50 Through The Eyes Of An $11 Hot Dog Vendor

Resume

Freelance journalist Gabriel Thompson makes his living writing about how other people make their livings, and he most recently set his sights on a $13-an-hour job at Super Bowl 50, the spectacle that took place last weekend in Santa Clara, California.

"You know, I didn't actually go into it thinking that Super Bowl conditions or stadium conditions would have the same low wage abuses that I found when I worked at a poultry plant in rural Alabama or working in the fields harvesting lettuce in Arizona," Thompson says.

Gabriel Thompson's story, "I was a Super Bowl Concession Worker," appeared in Slate Magazine and was produced in partnership with the Investigative Fund at the Nation Institute.

"I had put out my application for a bunch of different jobs at the stadium," he says. "You know, I was interested in trying to learn a bit more about what it's like for stadium workers. I was actually pretty up front. I just said, 'I'm a freelance journalist and I need some more money,' which both are very true. And they hired me."

There was one woman behind me who was yelling about how we were the 99% going to serve the 1%.

Gabriel Thompson

Thompson's Super Bowl story begins not at Levi's Stadium — the brand-new, high tech building that was constructed using more than $100 million in public funds after a campaign using the slogan, "Yes on Jobs!" — but at Avaya Stadium, where thousands of workers assembled to be bused in for their day's work.

GT: For the first 20-30 minutes, people are mostly talking about who they think's going to win, what celebrities might be there, if President Obama is going to be there. And it's a beautiful day. I mean, there had been a string of rainy, cold days, and this Sunday was going to be in the 70s. And so there was an excitement that, as you sort of wait and wait and wait, went away bit by bit.

There was one woman behind me who was yelling about how we were the 99 percent going to serve the 1 percent, and here they had us being bused in in school buses while folks coming down from San Francisco were going to be in these fancy, luxury, tinted window mega-buses. It was not like a little bit of grumbling. It was pretty overt on that line.

BL: That's what they want, right? A lot of angry people showing up to be concession workers at the Super Bowl.

GT: Well, yeah, now I look back on it, thinking about that whole day, and it was just sort of the opening shot. It was kind of an idea of, they thought a lot about many things about the game. They obsessed over the turf, but it became clear very early on that they hadn't thought very much about the folks who would be — the thousands of people — who would be sort of working behind the scenes making it happen.

BL: Now, of course the National Football League tells us that the Super Bowl is a great party. It's a celebration, possibly the biggest one this country sees, so I assume that all the partiers were polite and courteous as you took their orders and delivered their food to them.

GT: Well, you know, they were not too bad. We ran out of hot dogs an hour before the game started, I believe. And so, the idea that you'd go to the Super Bowl and you pay all this money and you have access to this exclusive club and that club doesn't have hot dogs? There's nothing we could do about it, but we had to kind of absorb a fair amount of frustration over that.

BL: I can't get out of my head the image of somebody going to the Super Bowl and ordering a hot dog.

GT: Actually, it was not a hot dog. It was a "jumbo" dog.

[sidebar title="Complete Super Bowl Coverage" width="630" align="right"]For more of OAG's Super Bowl coverage, click here.[/sidebar]

BL: How much did it cost?

GT: The jumbo dog, I think, was like $11 or something. It wasn't cheap. But I think at that point people have come to the Super Bowl, a lot of them are spending more than $10,000 for their tickets. There wasn't as many complaints about exorbitant prices, I think, because the whole thing is just ridiculous.

BL: But when the day's work was over, you were able to head straight home and count up all the money that you'd made, right?

GT: They had no well-thought-out plan for getting the employees out of that stadium. So I walk through the stadium to go get the shuttle after I've clocked out, and there's a line of thousands and thousands of employees standing there on this little path against the tennis court that are kind of getting pressed in. And as more people come and the line doesn't move, it gets tighter and tighter. We were in that line -- I was in that line for three hours. After 13-14 hours on your feet, it was excruciating. Two women I saw sort of broke down crying and had to be escorted out. People started pushing. They were loudly chanting, "We want to go home."

On one level, some of it might have been unavoidable, some of the waiting. But the last sort of indignity is that a lot of the workers that were in that line for all those hours should have been paid according to California labor law. But it was all off the clock. So of my 16-hour day or so, four of those hours, or five of those hours actually, I was not getting paid for.

It's not surprising that Thompson found unfair labor practices at the Super Bowl. He was looking for them. They were there. But before we let him go, we asked him to tell us one more story from his time at Levi's Stadium, and it begins again with standing in line, this time to clock in for a day's work.

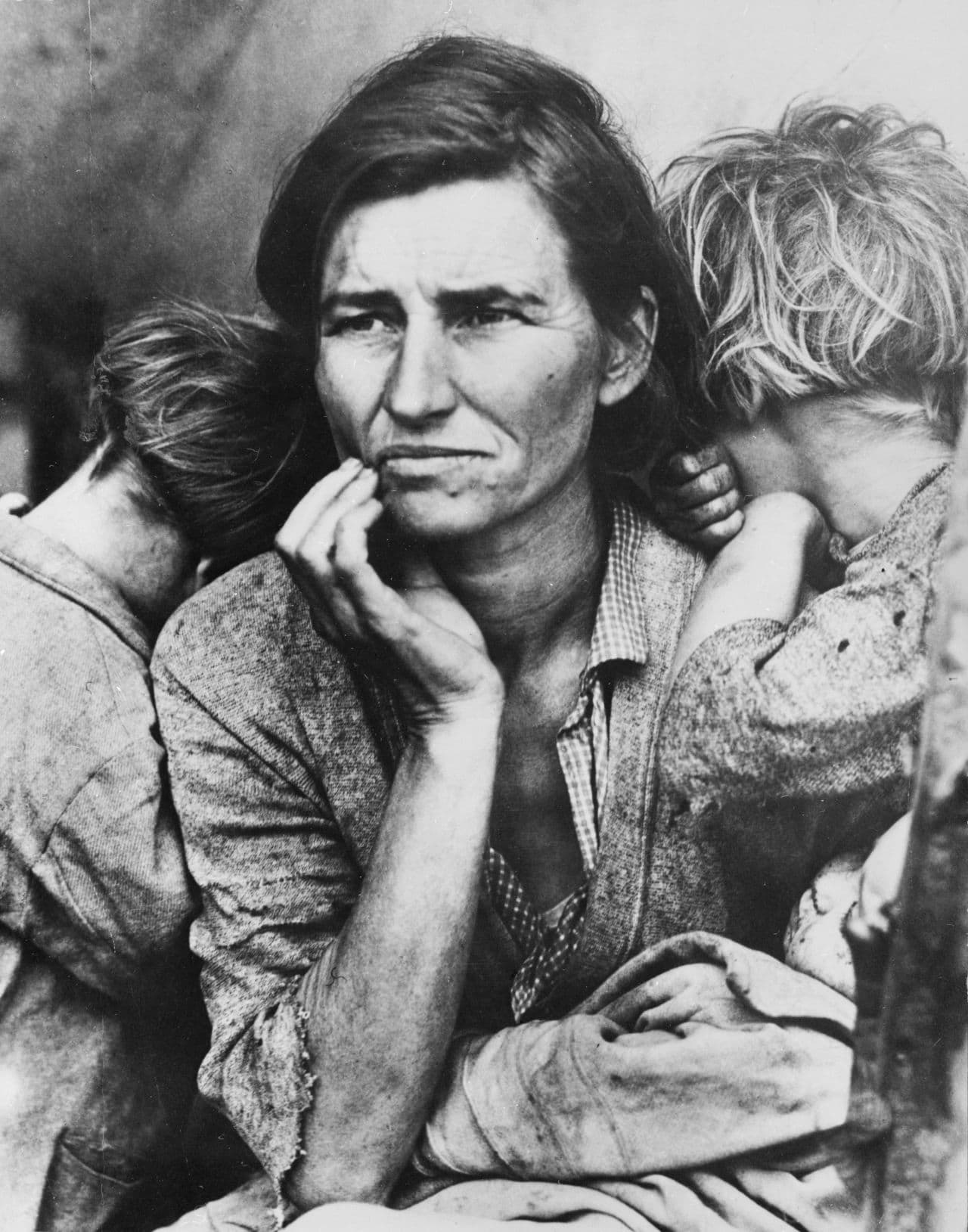

"Yeah, well, the company I work for, Centerplate, they have offices on the fifth floor where the luxury suites are. And as you walk along that hallway, there's sort of a private art collection to be enjoyed by folks in the luxury seats. Part of the collection right outside the company office includes both a charcoal pencil portrait of John Steinbeck where it actually has one of his quotes which I believe it was, "To live at all is to have scars." And then across from that was Dorothea Lange's classic migrant-mother photograph, of a Dust Bowl migrant-mother and her kids.

"You know, the juxtaposition of folks sort of being nickled-and-dimed in the heart of Silicon Valley at the fanciest, most high-tech stadium in the world — during the biggest, most profitable, most kind of, in some ways, grotesque or fabulous (whatever your perspective is) event — it was definitely, it went in my notebook right away."

This segment aired on February 13, 2016.