Advertisement

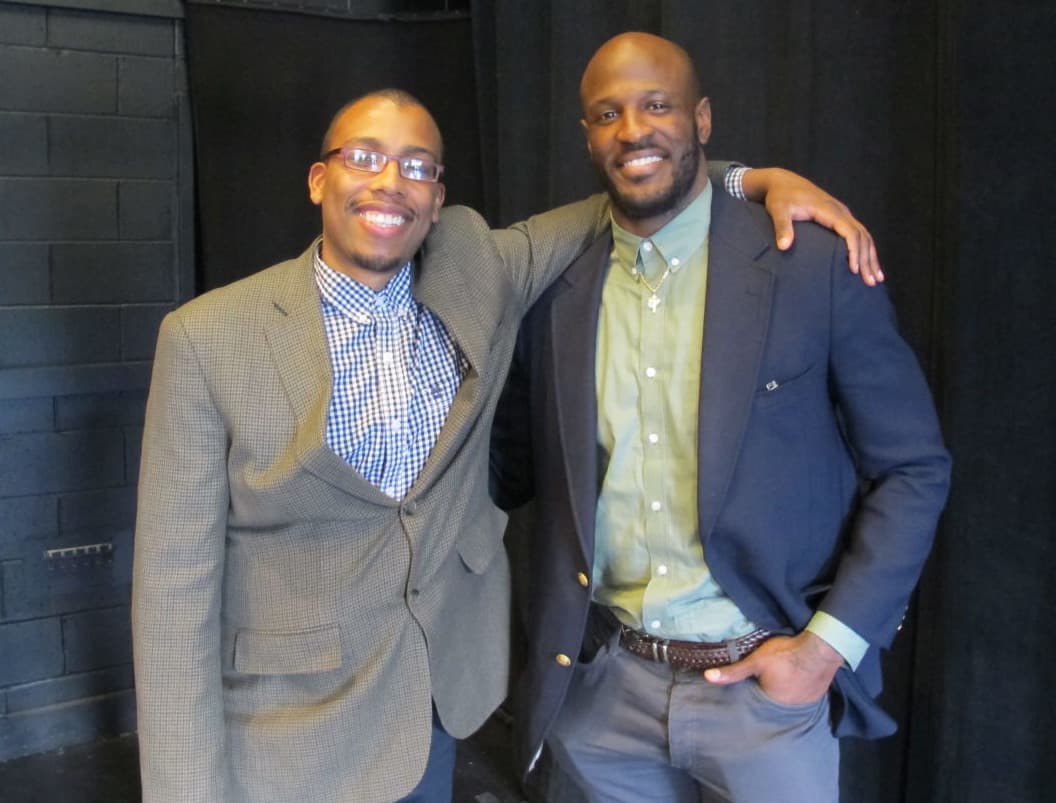

Onaje Woodbine's Spiritual Journey Leads Back To The Court — And Stage

Resume

53 years ago, I arrived on the campus of Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts. Like both Presidents Bush, I would spend several years there.

None of their classmates — and none of mine — were female. Almost all of their classmates — and almost all of mine — were white, as were all of the men who taught us.

I’m not acquainted with either former president. I understand that they were happy at Andover. I can’t say I was. But I recently went back to meet with some people involved in what seemed to me the sort of project that wouldn’t have happened when I was there.

"We’re putting on this play, which is really exciting, because it was written by our very own Dr. Woodbine," says Ashley Scott, a senior at Andover. She’s female, and she’s black. She’s sitting in the audience section of a small theater space in George Washington Hall.

"I don’t usually participate in theater or dance productions," Scott says. "This is actually my very first one in the time I’ve been here, but Dr. Woodbine was my basketball coach for two years, and I really felt like if I connect with him again before I left, it would just be amazing, especially with basketball involved."

'A Glorious Revelation'

And basketball is most certainly involved. It has been involved in the life of professor and coach Onaje X.O. Woodbine since he was a child.

I knew it in my bones. I could feel it, but how to say it in a way that would make sense. It took 10 years to actually find the language to express what was actually happening in this space. That was the struggle.

Onaje Woodbine

"Probably when I was 12-years-old, and I lost my coach and father figure, Manny Wilson," Woodbine says. "My mother was a single parent, and he meant everything to me. He was my mentor. He opened the gym on Saturday mornings when we would have been out in the street, probably contending with gangs. When he passed away, I lost my innocence. And I went to the court. And I was looking for Manny. I felt him there, and ever since then, the court became a place for me — for memory. A place where I go back and recover my innocence, I guess."

While the students rehearse the play he’s written, Woodbine and I talk about that connection to basketball...that reverence for the court as an arena for ritual. It might not have developed if Woodbine hadn’t been an excellent player. He played for two years at Yale University. Then in 2000, after his sophomore year, he quit the team, and in a letter to the Yale Daily News explaining his decision, he referred to his determination to pursue “the higher aims of divine purpose and truth,” which, as it turned out, brought him back to the basketball court.

"That was the glorious revelation," Woodbine says. "I knew it in my bones. I could feel it, but how to say it in a way that would make sense. It took 10 years to actually find the language to express what was actually happening in this space. That was the struggle."

As a graduate student in philosophy and psychology of religion at Boston University, Woodbine did his research by playing basketball on the same playgrounds in the Roxbury, Dorchester and Mattapan sections of Boston where he’d played as a teenager. Some of the tournaments in which he played served as memorials to black men who’d died young. Their images and names were preserved in banners hung on the fences around the courts. After games, Woodbine would try to explore with the other players the meaning of what they were doing.

"I remember the first interview I did was C.J., a young man who I write about in the book," Woodbine recalls. "And we’re sitting there, and I ask him, 'What is the most profound experience you’ve had on the court?' And he immediately goes into when his cousin was shot and murdered. And he said, 'I got on the court with a sad face on, but no one could steal the ball.' And he said, 'I don’t know what it is, but my cousin just held the ball for me.' And then I began to see the pattern, over and over and over again, in the other stories."

A 'Double Consciousness'

Woodbine found that basketball as ritual didn’t necessarily translate into basketball as transcendence.

"Today, C.J. is in prison," Woodbine says. "He just mailed me a letter, telling me that he’s playing ball in prison, and he’s finding hope in basketball in prison. It gives him a sense of transcendence that he can go on living, but it has not changed the external circumstances in his life."

"Basketball is tremendously important to the young men about whom you’re writing," I say. "Some of them even say, 'I don’t know where I’d be without basketball. I might be dead.' But does it have the capacity to take them beyond basketball?"

"These black young men are pushed to the court by poverty, they’re pushed to the court by racism, they’re pushed by this sense of oppression," Woodbine says. "But on the other hand, when you get into that space, you can experience a level of freedom that helps to resist and transcend that. And so how do I live with this double thing, this double consciousness, in this space?"

It’s a question that resists an easy answer, which is perhaps why it provoked Onaje Woodbine to write his book, "Black Gods of the Asphalt," and to take the project even further.

From The Page To The Stage

"It was storytelling," Woodbine says. "This was inner-city, street-level storytelling. And I thought, 'Why not actually, consciously, do this on the stage and create a conscious, ritual space in the theater? And so, I wrote a script with my father and my wife to try to tell these stories in a way that can impact audience beyond the streets."

"And involve characters," I say, "who are not of the streets, at least in some cases. These are not street kids."

He laughs.

"You’re laughing again, but I’m right, right?" I ask.

"You’re right," he says. "Most of these kids are not. What’s been profound for me is the process of theater, of coming up with a production is in itself like ritual."

Even as Dr. Woodbine and I talk about his play, which features the stories of three young black men and the people who are most important in their lives on and off the basketball court, two Andover students bring the words of his characters to the small stage.

"You think this court is empty?" asks one of the students who is playing a character named Alice. "When I’m talking, it ain’t just me talking. When I’m singing, boy, it ain’t just me singing."

Alice is addressing her basketballing grandson, Derrick.

"I got a whole symphony of angels with me, boy," she says. "What’s wrong with your ears, your eyes and your heart, Derrick? You can’t hear that?"

"Grandma, when I think about it, that’s how I play basketball," Derrick says. "That’s where I get all my pain out. My mother ain’t give me nothing but pain my whole life, Grandma. Foster homes. You know I almost got raped that last time my mother sent me to a foster home? A few nights ago, my mother locked me out of the house all night."

"What do you hope happens as a result of folks seeing this play?" I ask Woodbine.

This was inner-city, street-level story-telling. And I thought, “Why not actually, consciously, do this on the stage, and create a conscious, ritual space in the theater?"

Onaje Woodbine

To “overcome the ideas and concepts that divide us.” It’s a brave ambition. Perhaps it’s never been more necessary. It’s impossible for me to imagine anybody trying to do something like that at the Andover I used to know. But in a place populated by students of both genders, students of various colors and backgrounds, and a teacher/basketball coach who came up through the street ball ranks, maybe something will come of it.

The play based on Onaje X.O. Woodbine’s "Black Gods of the Asphalt" will be performed in mid-May at Phillips Academy — a better reason than most for me to go back again.

This segment aired on April 30, 2016.