Advertisement

Dodgers Great Maury Wills And The All-Star Game He Almost Missed

The Brooklyn Dodgers brought Jackie Robinson into the Major Leagues in 1947, and that changed everything for black ballplayers, right?

When Robinson retired, Maury Wills, also under contract to the Dodgers, was finishing the fifth of his eight seasons in the organization’s minor league system.

In 1959, Wills finally got the opportunity to demonstrate his specialty — stealing bases — in the bigs. Three years later, he stole 104 of them and made the National League All-Star Team.

Since he had grown up in Washington, D.C., he was especially pleased that the game would be held there. Wills spent time with family and friends before heading to the ball park alone, rather than with the other players.

Michael Leahy, who has written often about Maury Wills, recalls the consequence of that decision.

"When he arrived at the players’ entrance, he encountered a security guard, gave his name, Maury Wills, the Los Angeles Dodgers, a member of the National League All-Star squad," Leahy said. "The guard didn’t believe him, didn’t believe he was Maury Wills, despite the fact that Maury was carrying his Los Angeles Dodgers blue-colored equipment bag, and refused him entry. He can still see the security guard, still hear his voice, in his words can hear the tone of his voice."

Wills told Leahy it went like this:

"Get outta here. I’m not gonna say it again," the security guard said. "You don’t belong here, boy."

"I’m a player," Wills responded.

"I told you to move, boy," the guard said.

"A panicked Maury, at some point during the conversation, saw the then Cincinnati Reds’ great outfielder Frank Robinson and called out to him in an effort to get Frank to say to the security guard, 'Yes, I know him. That’s indeed a player on our team,'" Leahy explained. "And Maury called out, the security guard wheeled to Robinson and said, 'Do you know this guy?' And Frank responded, 'Never seen this guy in my life.'"

"He can still see the security guard, still hear his voice, in his words can hear the tone of his voice."

After a Hall-of-Fame career, Frank Robinson would go on to become MLB’s first black manager. His sense of humor may seem twisted, but certainly he knew what his All-Star teammate had been through.

Anyway, Wills eventually made it past the security guard with the help of a National League official. When he took the field in the pre-game introduction, his reputation as a base stealer preceded him.

"Maury Wills. Boy with the flying feet. Maury Wills of the Los Angeles Dodgers," the broadcast announced.

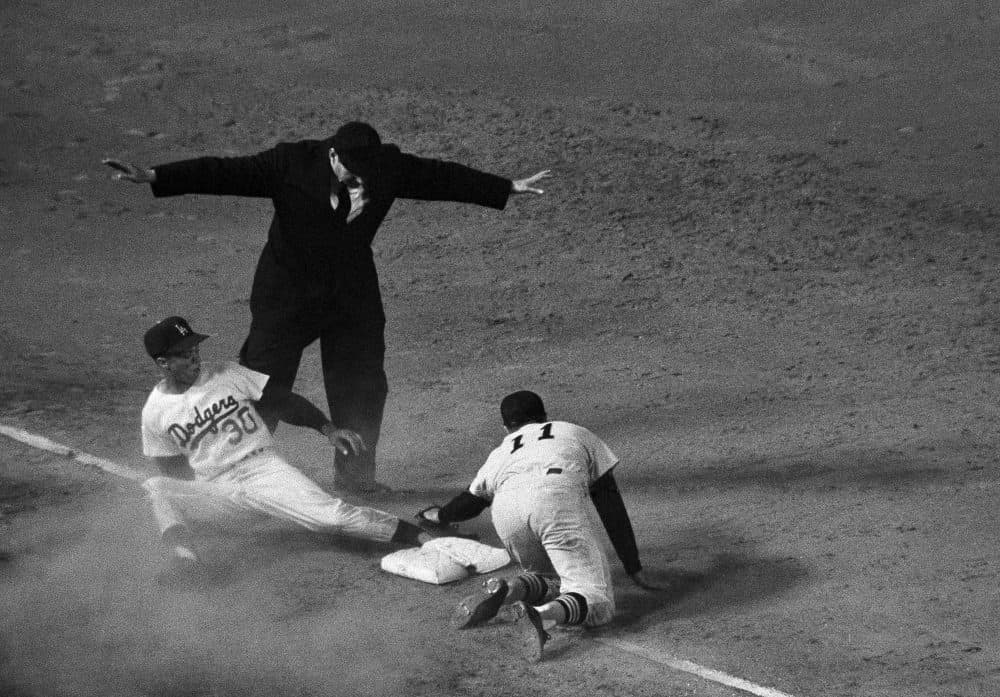

"And you had Maury Wills on that day, who had been rebuffed by the security guard, allowed into the ballpark, and then went on to have this majestic game," Leahy said. "Was the game’s Most Valuable Player in a 3-1 National League victory. Stole bases and ran the American League ragged. Was the MVP, and there’s newsreel footage of President Kennedy applauding as Maury Wills is doing all this.

"Maury said it was wonderful that day to walk out of the stadium with a trophy, to be the Most Valuable Player of the game, the best player on the planet earth on that day. And on Maury’s way out, as the team exited, Maury made sure that the security guard had a look at that nice trophy that he carried as he left the ballpark. But still he couldn’t get out of his mind that conversation with the security guard. It haunts him to this day."

Wills had been with the Dodgers for three and a half years. He was 29 years old. But at 5’11”, 170 pounds, he was not a physically imposing fellow. Do we know that the confrontation with the security guard was purely a racial incident?

"Maury believed it was, and, you know, it was an odd intersection that day," Leahy said. "I mean, we’re talking 1962, a year when Maury would become the National League’s Most Valuable Player, would break Ty Cobb’s single-season stolen base record, and so you had this giant of the game there for the All-Star Game, a man who was going to be the first African American to break a revered record of a white legend. And yet, one could be on the cover, say, of Sports Illustrated magazine one week in 1962, if you were black, and the next week be denied service at some restaurant or hotel in the United States."

To some, the summer of the 1962 All-Star Game probably seems distant. Not to me. I was a year short of high school. I remember watching Maury Wills run. And I remember that before Henry Aaron broke Babe Ruth’s career home run record 12 years later, Aaron received death threats from people who didn’t want to see that distinction in the hands of a black man.

Professional baseball has changed in lots of ways since then. Great black athletes today seem to be more likely to choose careers in basketball or football than baseball, and Major League teams are inclined to look for talent in the Latin American countries, where that talent is less expensive to develop.

But when we consider what’s happened and what is happening today to minority citizens who lack the celebrity of pro athletes, does what happened to Maury Wills before the 1962 All-Star Game seem all that distant?

Michael Leahy included Maury Wills in his new book, "The Last Innocents: The Collision of the Turbulent Sixties and the Los Angeles Dodgers."

This segment aired on July 2, 2016.