Advertisement

After Gunshot Wound, Former MLB Umpire Steve Palermo Was Told He'd Never Walk Again

At the first game of the 1991 World Series, Steve Palermo got to do something lots of baseball fans have probably dreamed of doing. He got to throw out the ceremonial first pitch. So, he was thrilled … right?

"Um, it was OK," Palermo recalls. "But it wasn’t umpiring."

For 15 years, it had been umpiring in the major leagues for Palermo. And it shouldn’t have stopped when it suddenly did.

From Little League To Major League

He’d taken the fast track to the top of his profession, which usually requires as much time, determination and luck as getting to be a major league player requires. Sometimes more. But when he was a 19-year-old kid umpiring a little league all-star game, Palermo impressed Barney Deary. This was a guy who knew what he was talking about. Deary supervised minor league umps. And he told Palermo to consider a career in the game. The kid figured he was on his way.

"What do you do? You work a couple college games and then you go right to Fenway Park?" Palermo recalls with a laugh. "I didn’t have any idea as to what it entailed."

At 21, he entered MLB umpiring school in Florida, and in 1977, just seven years after he’d worked that little league all-star game, Steve Palermo was in the bigs. It was an adjustment.

"You know, I was young and baby-faced, and one ballplayer — and I won't mention his name — but he used to call me teenager," Palermo says. "And so I used to call him pops, just to get back at him. But some of the guys I came up with, they're big, 240-, 260-pound guys, and they just intimidate you as soon as they got out on the field. And here I come, 180 pounds, slender, and they go, 'Let's see, we gonna pick on that big guy over there? Ah, let's yell at the skinny guy.' That's kind of how they approached it. But you earn the respect. You're not given the respect. And once you prove to them that you can do the job, then they leave you alone."

Advertisement

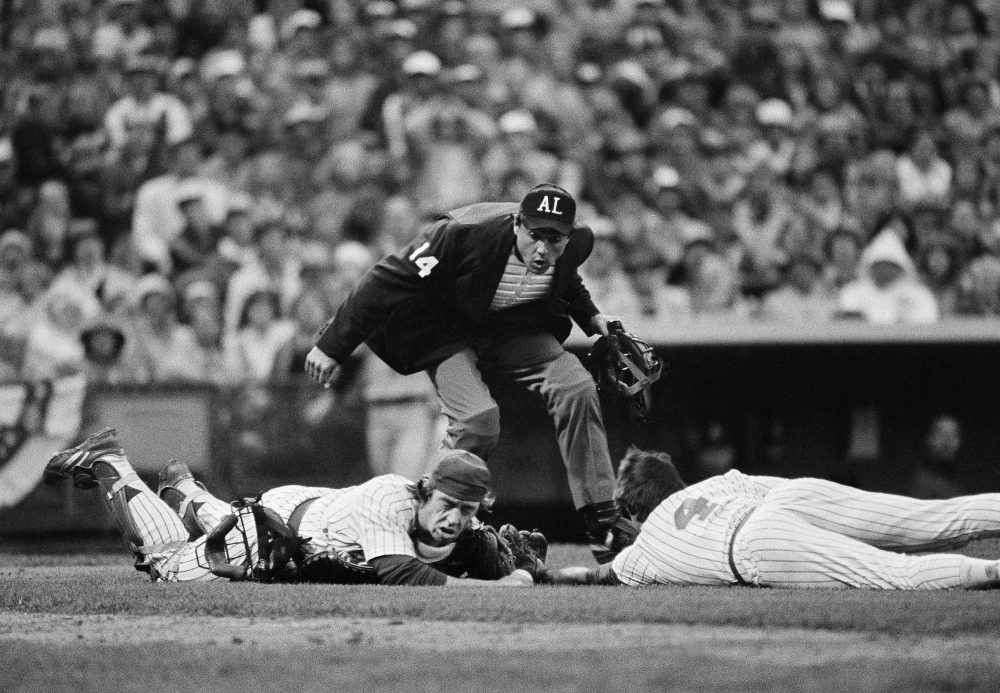

In a profession where every performance is evaluated and every opportunity is earned, Palermo climbed the ladder. He worked the All-Star Game, the American League Championship Series and the World Series. 1991 was looking like a banner year for Palermo: He married his wife, Debbie, and the Sporting News named him the American League’s top official.

Robbery In Dallas

And then in July, after he’d worked a Texas Rangers home game, he went out for Italian food with some friends in Dallas. All went well until Jimmy Upton, one of the employees at the restaurant, looked out the window at the parking lot and saw several men trying to rob a couple of waitresses who’d just left work.

"We came up and off the table and ran out, and we ran after the guys," Palermo says. "And one of them hollered out, 'Look out, look out, here they come.' Two of them ran toward a car, and there was actually a getaway driver in the car. One of the guys got disoriented, and he started running the opposite way. And a good friend of mine — a former football player at Southern Methodist — Terence Mann, we call him T-Man, and we took off after this guy, and we ended up catching him."

Somebody called the police. They said they’d have a squad car there in three to five minutes. They weren’t quite quick enough.

"And as we were waiting for the police to arrive, a car pulled up, about 20 feet from us, and a young guy got out of the front right passenger seat. It was one of the robbers that night and he had come back, pulled out a .32-caliber pistol and fired five shots into the crowd of people that were standing over his buddy. T-Man got hit three times. And the fourth bullet hit a wall, brick wall, behind us. And then the fifth bullet hit me, belt high, and tore a path through my body. And then instantly I was paralyzed. I just kind of melted into the pavement. I knew right away that, oh boy, this is serious. And I tapped my legs, and all I could feel was the sensation on the back of my fingers.

"Jimmy had taken a towel out of the back of his pocket and put it behind my head. And then I looked at Jimmy, and I said, 'Jimmy, if I die, you make sure that you tell Debbie that I love her.' And Jimmy, in his perfect Texas drawl, said, 'Stevie, there ain't no dying going on here tonight.'"

'I'm Going To Prove You Wrong'

Palermo was taken to a hospital and underwent surgery. When he woke up, his doctor had bad news.

"I knew right away that, oh boy, this is serious. And I tapped my legs, and all I could feel was the sensation on the back of my fingers."

Steve Palermo

"And he came in, and he kinda hedged and fudged a little bit and fidgeted," Palermo says, "and then he said, 'Steve, we just don't feel — with the exploratory surgeries, the CAT scans and the MRIs, the X-rays, everything — we just don't feel like there's the possibility that you'll walk again. The bullet just did so much damage.' I said, 'Doc, I appreciate — you know, I'm sure that's coming from a lot of experience and a lot of knowledge. But I'm going to prove you wrong.' And he said, 'Well, I hope you do.' He didn't say it with a lot of conviction but, um — and then we just set out on this long path of physical rehabilitation."

Initially, the plan was to teach Palermo to use a wheelchair. His wife, Debbie, encouraged the therapists to rethink that plan. The goal should be walking. Steve Palermo’s goal was to go back to work on the ballfield. This is a guy who loved his work.

More surgery would come in time. But step one had to be … well, step one. As soon as he was able, he started a program of rehabilitation that involved, among other things, trying to walk on a treadmill, right next to the treadmill on which a 6-year-old boy named Cody was also trying to walk. Cody had suffered a brain injury after being thrown from a horse.

"I'd be on a treadmill trying to walk where it was set at 0.111 miles per hour — the slowest speed — and Cody would get on his treadmill and he'd turn it up," Palermo says. "I'd look over there and say, 'Well, this little 6-year-old kid, he's not going to beat me.' So I turned up my treadmill. And he ramped his up, and now all of a sudden it's like the Boston Marathon."

Inspired by Cody and another child named Mitchell, who’d been hit by a car while riding his bike, Palermo improved. In the evening, he and the two children watched ballgames on TV. Palermo won’t say whether he second-guessed the umpires.

When he reached the point where he could walk — haltingly — on his own, he sent a message to the doctor who’d told him he wouldn’t be able to do it.

"Like, I joke all the time: I sent him my wheelchair — told him to stick it in his office somewhere," Palermo says. "And it was kind of like a reminder to him that you don't defeat somebody before you ever give the patient a chance to either fail or succeed."

'I'm Not Lucky, But I'm Fortunate'

Major League Baseball was impressed enough to offer that 1991 invitation to throw out the first pitch at the World Series. Initially, Palermo wasn’t sure. He was still using a brace and crutches. But eventually he convinced himself to test that possibility.

"Actually, for about week, my therapist Gwen and I, we were outside the rehab center, and I was trying to throw a baseball — see if I could get it to home plate," Palermo says. "Because there's no way I’m gonna bounce it. You never live that down, and I wanted to make sure that I could get it to home plate."

Palermo could. And on Oct. 19, 1991, in Minneapolis, Palermo took the mound.

Though Palermo would continue to visit ballparks, it would never again be to umpire a game. Over the years after Steve Palermo was shot, his friend Terence Mann, shot three times the same night, made a nearly complete recovery. Cody, the 6-year-old on the treadmill beside Palermo’s, got back to riding horses. One day Palermo received a photograph of Mitchell, his other recovery partner, at his high school prom.

Meanwhile, Palermo himself moved on to other work in Major League Baseball. He served in the commissioner’s office and was eventually promoted to supervisor of umpires.

"It's different, but I'm very, very — I'm not lucky, but I'm fortunate," Palermo says. "I'm still involved in the game. And it's really — it’s fun. It is fun. It's rewarding to see guys do well."

"I wanna ask you one more question," I say, "and I mean no disrespect: You ran out of the restaurant with these other guys. You scared the muggers away. The two women — the two waitresses — were safe. Do you ever find yourself thinking, 'Damn, I wish I hadn't chased that guy? I wish I'd just let it go at that?'"

"No, not really," Palermo says. "If you had run out that door and seen what these guys were doing to these women, you felt violated personally. And nobody — nobody — has the right to treat another human being like that. And was it stupid to chase 'em? Well, if they get away with it, then they're probably going to do it again. They're probably going to do it again. And, as a matter of fact, they had done it a few times that night. So it probably wasn't going to stop."

Satchel Paige, half great pitcher, half myth, is alleged to have said, "Don’t look back. Something might be gaining on you." Steve Palermo’s a baseball man, so maybe he’s heard that advice. Or maybe despite being shot and told he’d never walk again, he’s always been just too busy looking ahead.

This segment aired on January 14, 2017.