Advertisement

Hank Greenberg: Caught Between Baseball And His Religion

Resume

Let’s take a look at the standings.

It’s Sept. 10, 1934. With 20 games left in the season, the Detroit Tigers are four games up on the second-place New York Yankees. It sounds like a cushy lead, but remember, these are the Babe Ruth Yankees. Against these guys, a four-game lead with 20 to play is anything but safe.

"The Tigers could could win the pennant," documentary filmmaker and baseball superfan Aviva Kempner says. "And they had not come in first since 1909."

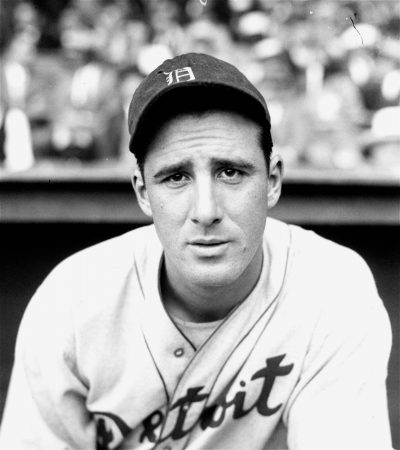

The Tigers are riding the hot hitting of 23-year-old phenom Hank Greenberg. Playing in only his second full season in the bigs, Hank is batting .338, leading the league in doubles...

"And I was probably the only batter in the lineup that was not in a slump," Hank recalls in a clip from Aviva's documentary, "The Life and Times of Hank Greenberg."

Now, just hours before a crucial game against the Boston Red Sox, Hank sits alone in the clubhouse. He’s perfectly healthy, and enjoying the best season of his young career, but, still, something nags at him.

Today is Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year.

"He’s a nice Jewish boy from New York, grew up Orthodox," Aviva says. "And what is he going to do, living in Detroit during this pennant race?"

Jewish holidays aren’t just family gatherings or celebrations — instead, they come with a long list of ritual prohibitions. Traditionally, these include driving, writing, using electricity, but most importantly, working. And as much as baseball is a game, for Hank, it’s his job.

It’s not an easy decision for Hank. He isn’t personally very religious, but still, his tradition is important to him. But more than being about his own religious identity, this decision has even deeper implications.

'Hotbed Of Domestic Anti-Semitism'

In 1930s America, being Jewish was very different than it is today. Neighborhoods barred Jews from buying homes, stores had signs which read, "No Jews or dogs allowed," and the 1924 Immigration Act had installed quotas which significantly slowed Jewish immigration to the U.S.

And right in Hank’s backyard ...

"Detroit was really the hotbed of domestic anti-Semitism," Aviva says.

Car magnate Henry Ford, perhaps the most famous Detroiter of that era, spent much of his spare time distributing anti-Semitic propaganda. His newspaper, The Dearborn Independent, went so far as to call Jews, "the World’s Foremost Problem."

"But more importantly, there was Father Charles Coughlin," Aviva says.

Coughlin was a Catholic priest in Detroit who used his radio program to spread anti-Semitic messages to an estimated 30 million weekly listeners:

We are Christian insofar as we believe in Christ’s principle of "Love your neighbor as yourself," and with that principle, I challenge every Jew in this nation to tell me that he does not believe in it!

And Hank experienced this anti-Semitism up close.

"They were calling him every name in the book," Hank's son, Steve, recalls. "'Sheeny,' 'Kike,' 'Throw him a pork chop; he can’t hit that.'"

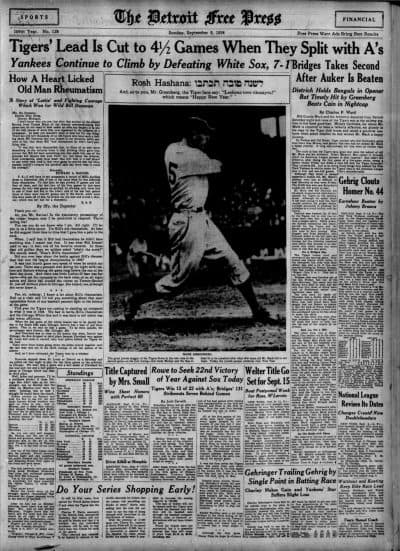

Hank was worried that choosing to sit on Rosh Hashanah might inspire even more vitriol, but a curious thing happened. The city’s major paper, the Detroit Free Press, rallied behind him. The day before Rosh Hashanah, at the top of the sports section, was a headline written from right to left in strange, large letters. It read, "L’shana Tova Tikatevu."

"In Hebrew letters, front page, it was as if war had been declared. The type was that big," Steve says.

An English headline, right next to the Hebrew, read: "And so to you, Mr. Greenberg, the Tiger fans say, 'L’shana Tova Tikatevu!' which means 'Happy New Year.'"

According to Jonathan Sarna, professor of American Jewish History at Brandeis University, this may be the only instance of a major American newspaper with a Hebrew headline. And think about the what it took to make this a reality. This was before digital printing, so the Free Press would have had to get special metal plates just to print these three words.

"I have no idea, to this day, where they got the metal type for this Hebrew," Aviva says.

And immediately below the Hebrew headline, there was a huge picture of Hank mid-swing. It was almost as if the paper was saying, "Please, Hank. We need you."

'How's Hank Doing?'

OK. Back to where we started. It’s late afternoon on Rosh Hashanah, and Hank is sitting in the Tigers clubhouse in his street clothes — he actually came here straight from synagogue. He looks up and spots coach Mickey Cochrane, who tells him this: "I need you out there, but in the end, it’s your choice."

Hank decides to play.

As the game gets underway, congregants at the synagogue are on the edge of their seats.

"While the cantor was singing, he would stop for a minute and say, 'How’s Hank doing?'" Tigers fan Harold Allen recalls. "The whole interest of the city of Detroit was Hank Greenberg."

Listen to OAG anytime. Subscribe to the podcast. iTunes | Stitcher | RSS link

The Tigers are in a nailbiter against the Boston Red Sox. They trail 1-0 for most of the game, but Hank is the lone bright spot for Detroit, tying things up with a solo homer in the seventh inning. Now, in a 1-1 game, he calmly strolls out of the dugout to lead off the bottom of the ninth. Hank digs in, while Red Sox pitcher Gordon Rhodes peers in for the sign. The crowd grows into a steady roar, as Rhodes winds up and fires.

Hank’s bat whips through the zone and the ball rockets up and out of the park. A walk-off home run from the Hebrew Hammer, as the Tigers win, 2-1.

The next day, a picture of Hank — mid-home run trot — graces the sports section once again. This time, the headline reads: "A Happy New Year for Everybody."

So, happy ending for Hank and the Tigers, right? Well, the thing is, there are a whole bunch of Jewish holidays in the fall, so Hank’s story isn’t done yet. Up next? The most important one of all: Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement.

Was It Kosher?

Over the next week, Detroit fans waited on pins and needles to see if Hank would play.

And, believe it or not, the best place for fans to find out if Jewish law might allow him to was, of all places, the sports page of the Detroit Free Press.

"And all the newspapers in the city were debating, would the power hitter play or not?" Aviva says.

Jewish ritual practices weren’t exactly the kinds of things most people knew about, but before Detroiters knew what hit them, technicalities of Jewish law were being expounded in the sports page. The most important question to answer: Was it kosher that Hank had played on Rosh Hashanah?

One rabbi "decreed that Hank Greenberg could play because he found an obscure text in the Talmud that said that on Rosh Hashanah the children played in the streets of Jerusalem," Steve, Hank's son, explains.

And looking back on Hank’s two Rosh Hashanah home runs, the famed writer "Iffy the Dopester," (not Jewish as far as I know) issued his verdict in the pages of the Free Press:

I do not know anything about the law of the most ancient Church in the world. That’s all for students of the Talmud, but I’m here to testify in the world as a baseball expert that the two hits he made in that ball game were strictly kosher.

Let’s not take for granted the basic fact that a major American newspaper in the 1930s was debating intricacies of Jewish law. In a place famous for its anti-Semitism, it showed just how much Hank was respected throughout Detroit.

But at the same time, some were less than thrilled with Hank’s decision. That rabbi who said Jews were playing in the streets on Rosh Hashanah? Well, according to Jewish historian Irwin Cohen, it’s more complicated than that.

"He came out very upset after that — that he was misquoted," Cohen says.

Cohen says that Rabbi Thumin did say Jews had played ball, but he meant children, so it wouldn’t apply to adults. And he says that according to Jewish law, it would be difficult to permit playing in a professional baseball game on Rosh Hashanah.

"He was a very Orthodox man — long white beard, dressed in black. He’s from a long line of Orthodox families," Cohen says. "Rabbi Thumin did not give Hank Greenberg permission to play on Rosh Hashanhah."

Hank received phone calls and telegrams from rabbis and Orthodox Jews who felt that he had given up on his religion, people who claimed he’d make it harder for Jews to stay true to their faith in the future. To this part of the Jewish community, Hank represented a very real fear: the loss of traditional Jewish life. Hank seemed like someone who, when push came to shove, would choose his livelihood over his religion.

Sitting Out Or Suiting Up?

Eight days after Rosh Hashanah, with the Tigers leading the Yankees by 7 1/2 games on Yom Kippur, Tigers fans were anxiously awaiting Hank’s decision. He’d played on the Jewish New Year, but would he play on the most solemn day in the Jewish calendar?

For Hank, religion was ... complicated. The week before, when he’d been asked to lead a prayer, he said, "I am only a ballplayer. Give it to someone else who really deserves it."

But still, when it came to Yom Kippur ...

"Hank Greenberg decided to honor his Romanian-born parents by trekking to the synagogue instead of suiting up during this raging pennant race," Aviva says.

"The only way I would ever think that I might have been a hero in those days was the day I walked into Shaare Tzedek Temple on Yom Kippur," Hank says in Aviva's documentary. "The poor rabbi’s standing on the podium, davening, praying, and suddenly I walk in and everybody in the congregation gets up and [claps], and the poor rabbi looks around — he doesn’t know what’s happening, and I’m embarrassed as can be, because it was all totally unexpected."

With Hank sitting out, the Tigers lost, but once again, the Detroit Free Press didn’t waver, publishing a poem from Edgar Guest.

"And it said, 'We shall miss him in the infield and shall miss him at the bat — he’s true to his religion and I honor him for that,'" Steve Greenberg says.

Making A Stand

Think about that newspaper, with those three Hebrew words, "L’shana Tova Tikatevu," emblazoned on the sports page. Then take a second to think about when and where this was happening. A time when Jews were viewed as a threat to America.

And for some, they still are.

"Let’s be real clear," Aviva says. "Hank Greenberg did not play on Yom Kippur in '34, as Hitler was rising in Europe, and that’s what made it even more powerful. And after what happened in Charlottesville, I hope some more Jewish baseball players don’t play on Yom Kippur."

Since Hank did it, great Jewish players like Sandy Koufax and Shawn Green have also chosen to sit out on Yom Kippur. But this ability to take a stand depends on the press. In 1934, the Detroit Free Press truly had the power to frame Hank’s decision, and it didn’t choose to present Hank as some sort of radical outsider with a strange and inscrutable religion.

Instead, the Free Press portrayed Hank’s decision with the complexity it deserved, describing the real conflict of identity that Hank, and to be honest, many Jews, felt at the time.

"I think the newspapers, just like today, played a very important role in saying, anti-Semitism, racism, do not belong on the ball field, do not belong in society," Aviva says. "The fact of the matter is, the way the Free Press covered 'will Hank play on Rosh Hashanah?' was again the power of the press saying it’s OK for a player to make a stand."

This segment aired on September 23, 2017.