Advertisement

NCAA Show

Power And The NCAA: One Athlete's Fall From The Big 12 To The Oil Fields

ResumeThis story is part of Only A Game's special episode about the past, present and future of the NCAA. Find the full episode here.

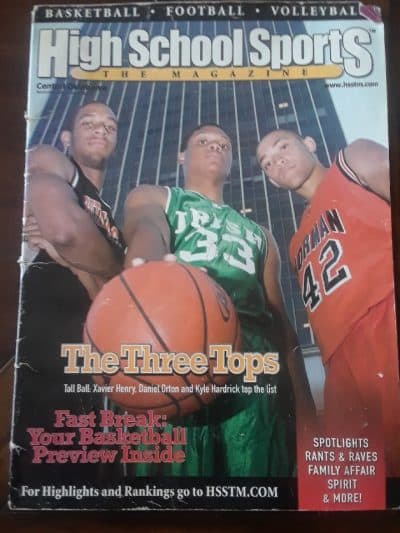

Kyle Hardrick was once a top basketball prospect. Now he pulls 12 hour shifts in the oil fields near Odessa, Texas.

"I worry about him," says Kyle's mom, Valerie. "I wake up in the middle of the night dreaming that I walk in the door and he's hanging or he shot himself, because he's that depressed. And then when basketball season comes around, that's even worse."

Hoop Dreams

Just a few years ago, Kyle was a high school basketball player suiting up for one of the nation’s best club teams. He played alongside guys who are now in the NBA. His dream was to make it to the pros.

"I wake up in the middle of the night dreaming that I walk in the door and he's hanging or he shot himself."

Valerie Hardrick

"'Cause that's what I wanna do when I grow up — I wanna pay for my family, so they don't have to work anymore, you know what I'm saying?" Kyle Hardrick says in the 2016 documentary "The Business of Amateurs."

Kyle has stopped speaking publicly about his basketball career, so all the quotes you'll read from Kyle come from that documentary.

At the end of his freshman year of high school, Kyle committed to play at the nearby University of Oklahoma for coach Jeff Capel. Kyle was excited. Valerie was relieved.

"Coach Capel said, 'Hey, we're gonna take care of your son,'" Valerie recalls.

In 2009, Kyle enrolled at Oklahoma.

"I remember it was my freshman year. It was before our first little scrimmage thing. I was guarding Tiny Gallon," Kyle recalls. "He hit my knee, and I fell back and once he fell on me, you hear an instant pop. I remember the trainers and the managers were like, 'Oh, god. what happened?' Sound like a shotgun."

Valerie says the coaches told her they did an X-ray and there was nothing seriously wrong.

So Kyle kept practicing — though he says the pain didn’t go away.

"They still make me do drills. Still did drills," Kyle says.

After this went on for over a year, Valerie decided to take Kyle to a family doctor.

Kyle was diagnosed with a torn meniscus.

"And when I heard that I was just shocked," Kyle says. "I was like, 'So this whole time I had a tear?' I was really mad that day. I remember that day I didn't talk to nobody."

A Power Disparity

Kyle underwent surgery on March 11, 2011. According to Valerie, there was permanent damage to Kyle’s knee.

She says the doctor told her, "'Yeah, you know, if this would've been taken care of a year ago, he wouldn't have been in this situation he's in.'"

To make things worse for the Hardricks, Oklahoma refused to pay for the surgery.

In a statement to Only A Game, the University of Oklahoma Athletics Department said, "Oklahoma student-athletes have access to a highly-respected and accomplished team of medical doctors. When student-athletes choose to seek physicians beyond those that work closely with us, as was the case with Mr. Hardrick, they do so at their own expense and risk."

But this is where the power disparity between universities and players really comes into play: there are no NCAA rules requiring colleges to pay for athletes’ health care. It's up to individual schools to decide what will be covered.

Most of the time, schools do pay for their athletes’ medical bills while they’re still enrolled. But the fact that the NCAA doesn’t obligate colleges to pay speaks to this power imbalance.

After the operation, Kyle started rehabbing in hopes of playing again. Meanwhile Oklahoma got a new head coach, a veteran college coach named Lon Kruger.

Valerie says Kruger called her and her husband in for a meeting.

"And he sat us at the table," Valerie recalls, "and he says, 'You know, Kyle needs to find a college that's suitable for Kyle.' We're going like, 'What?' He says, 'Yeah, yeah. Kyle really don't belong here.'"

That summer, Valerie says the family learned that Kyle had lost his scholarship.

And I should say here that most athletic scholarships are not for four years. They’re for a single year and they have to be renewed annually.

And, once again, the NCAA gives the power to the schools — coaches decide whose scholarship gets renewed. And since teams have a limited number of athletic scholarships, it can be in their interest to get rid of an underperforming player in order to free up a scholarship for a prospect.

Kyle transferred and tried to revive his basketball career. But the knee pain continued, and Kyle ended up needing another surgery.

"So after that he just gave up basketball," Valerie says. "He says, 'I can't do it anymore.'"

And in 2012, Kyle dropped out of college.

"So right now he's an angry, angry child," Valerie says.

"This is an issue that affects black families more directly than anyone."

Kevin Blackistone

'You Put Trust In These Universities'

As Valerie and Kyle Hardrick saw firsthand, the system of college sports established by the NCAA is set up so that power rests with the universities.

And as the Washington Post's Kevin Blackistone points out, there's a troubling racial dynamic to this imbalance. The majority of major college sports coaches and administrators are white. Meanwhile, the majority of athletes in big-time football and basketball are black.

"This is an issue that affects black families more directly than anyone," Blackistone says. "And so when we see black families putting so much emphasis on the athletic development of their children, particularly black males, because they are lured by the athletic system at a very young age, it's a big, big problem."

I asked Valerie Hardrick who she believed was at fault: Oklahoma or the system of college sports?

"It's a system of college sports," Valerie says. "You put trust in these universities. You trust them with your kid on and off the court, and once you're damaged good, they just kick you to the curb."

Check out more from Only A Game's episode on the NCAA here.

This segment aired on October 14, 2017.