Advertisement

Photographer Visits Alps For Final Portrait Of 'Babe Ruth Of Climbing'

Photographer Jim Herrington is sort of an odd guy. He'll tell you that himself.

"I'm an odd guy," Herrington recently told me.

He sometimes makes decisions that would make an economist cringe.

"I run from money and money runs from me," he says.

What Herrington means by that is this: he'll work on a project he thinks is important, even if it's not going to make him any money — even if it's going empty his own bank account.

This is a story about one of those projects.

Photographing Star Entertainers — And Climbers

Herrington's been a professional photographer for decades. He's taken photos of famous musicians for magazines like Vanity Fair and Rolling Stone. But just for fun in 1998, Jim took portraits of two 86-year-old men — both former climbers who had made some of the first ascents in the Sierra Nevada mountain range.

"Cassin wasn't in great shape -- that's all I heard at the time: 'He's not in great shape.' "

Jim Herrington

Herrington's always liked climbing and he was interested in these "past masters" — the men and women who ascended the mountains of the Sierra Nevada back when the equipment didn't help much and there weren’t endorsement deals.

Herrington set out to photograph more of these former Sierra Nevada climbers.

"A few have died before I got to them. Many are in elderly shape. I started noticing I was getting these people that were disappearing," Herrington says. "I realized no one else was doing this project, and maybe I had a certain responsibility to continue this and get the last remaining people from this era."

Herrington started using the money he was earning from his day job photographing star entertainers like Dolly Parton and the Rolling Stones to track down climbers most people have never heard of.

The project grew — first to include pioneering climbers from across the U.S., and then the entire world.

Herrington decided there was one particular man he had to track down: an Italian named Riccardo Cassin, who was the first to climb the Walker Spur — a nearly vertical wall of granite in the Alps.

Advertisement

"He was just one of the giants," Herrington says. "Ricardo Cassin looms large. He's like a Babe Ruth of climbing."

Herrington didn't know where Cassin lived or whether he'd be able to find him. And when Herrington began his search, the news he was hearing wasn't good.

"Cassin wasn't in great shape — that's all I heard at the time: 'He's not in great shape,'" he recalls.

Discovering Climbing In The Alps

When Riccardo Cassin was born in northern Italy in 1909, he certainly didn't seem destined to become the Babe Ruth of climbing.

Back then, most people climbing the nearby Alps were wealthy Brits. Cassin's family was poor. When he was just 3 years old, his father left to take a job as a miner in Canada. He died in an accident before Cassin ever got to see him again.

"Riccardo grew up with his mother and his siblings, with pretty much no money," Herrington says.

Cassin left school at the age of 12 to work as a blacksmith's apprentice. When he was 17, he moved to a small town on Lake Como called Lecco so he could work in a steel mill.

"But he discovered climbing, like a lot of kids did," Herrington says. "They were surrounded by rock walls and the great Alps. And what started as kind of scrambling and hiking for fun turned into an obsession."

Cassin and his friends called themselves the Lecco Spiders. Sometimes they'd travel hundreds of kilometers — first by train, then bike, then foot.

Cassin's best friend was Vittorio Ratti. Throughout the '30s they scaled mountains in the Alps and the Dolomites.

"So you can imagine these limestone Dolomite cliffs were straight up vertical — and this is ferocious and terrifying these days with modern gear. It's just simply astounding to imagine these guys going up with these horrible hobnail boots and the rope just tied around their waist," Herrington says. "There was no harness."

And these weren’t modern ropes. They were made of hemp.

"The rope would snap anyway if you fell on it," Herrington says.

In 1937, Cassin and Ratti became the first to scale a daunting granite wall less than a hundred kilometers northeast of Lecco: the Piz Badile. Cassin and Ratti were becoming famous.

"They had so much momentum — were just full of it — with the talent and the drive to do it. Ratti and Cassin were this perfect team," Herrington says. "But the war was coming on around Europe, and the fascists were moving in."

The Climbers In The Resistance

At the start of World War II, Cassin worked in a munitions factory, an assignment that spared him from fighting on the Italian side against the Allies.

Then in 1943, American, British and Canadian forces invaded Sicily and the southern part of mainland Italy.

With the Allies moving up from the South, the Germans increased their control in Northern Italy. A puppet government was based just 90 minutes from Cassin's home. By that point, Cassin and Ratti had joined the Italian resistance — and they weren't the only climbers to fight the Nazis. The mountain passes were important strategic points, and the climbers were useful fighters.

"They knew the mountains, they knew how to get around, and they could survive up there, so they were very instrumental," Herrington says.

According to The Independent, Cassin traveled between resistance cells based in the mountains and stashed weapons in his home.

It seemed like he and Ratti were both going to survive the war. But then on April 26, 1945, as the puppet state was collapsing, Ratti fired on German soldiers who were trying to leave Lecco. The Germans returned fire, and Ratti was killed.

"Something was taken away when Ratti was killed," Herrington says. "The war interrupted that momentum they had, that free-wheeling youth. Cassin was a changed man afterwards."

'He Just Looked Like A Piece Of Granite Himself'

Without his partner and best friend, Cassin still managed impressive climbs in the decades after the war. In 1961, at the age of 52, he led the first ascent of the south wall of Alaska's Mount McKinley, a feat that earned him a congratulatory telegram from President Kennedy.

Cassin continued climbing into his 80s, retiring with 2,500 climbs.

But by the time Jim Herrington set out to photograph Riccardo Cassin about a decade ago, the legendary climber was nearing 100 years old. Not only that, it was one of those times Herrington was low on cash. That didn't stop him from trying to track down Cassin.

"The communication was all very spotty, and it was all kind of espionage-like," Herrington says. "Maybe I would get a phone number of an alpine club in Europe or some kind of shaky contact in Poland: 'Call Niko at 2 a.m. and he'll give you the phone number that you then call.' But I finally got an address for Cassin and could write, and I got in touch with his son, Guido."

Herrington soon learned that Cassin was dying. He headed for Milan to get closer to Cassin and awaited further instructions from Guido.

"I remember thinking even at the time that I was going to commit all this — what little money I had — going way up to this remote village and just find out that maybe he died or I wouldn't find him," Herrington says. "But I finally got word that I could meet Guido at a train station up near Lecco on Lake Como.

"So I took a train early in the morning, and there was Guido waiting for me at the train station. And he spoke absolutely no English. And I know three words in Italian. So we gesticulated a lot, which is easy for him because he's Italian. And he took me high up in the hills above Lake Como where this vigil was taking place. They all knew his father was dying.

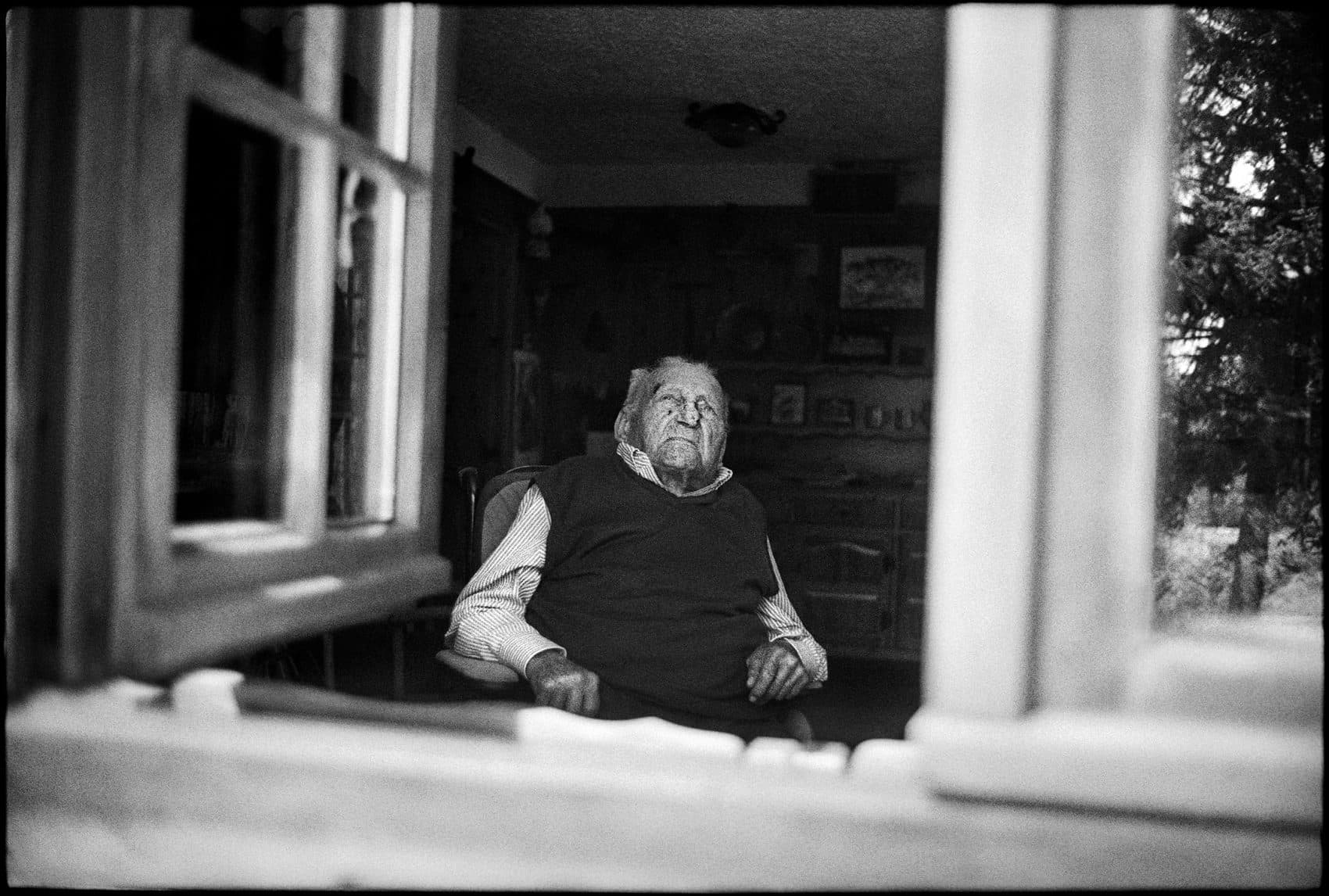

"The little kids were playing in the yard, laughing, drinking lemonade. The sunshine coming through the trees. It was just beautiful. It almost seemed to have a sepia filter in front of it. And there was the great man. They had him pushed up to the window on the inside of the living room in his chair. And he just looked like a piece of granite himself — just this incredible face and still a strong looking body. But his face was ravaged. He seemed to have some kind of skin cancer. Too many decades climbing too close to the sun is what I'm suspecting."

Cassin didn't have the energy to speak in his own language, let alone English. But Herrington spent over three hours in that room with him, sipping Rosato and taking pictures.

"You know, you grow up seeing the photographs and reading the stories, and then you're suddenly in the room with him, and you're looking at Cassin who's 100 1/2. He's just completely worn out. And he's dying in front of you," Herrington recalls. "But you just think of the vigor of the guy in the '30s going up through the storms on the Walker Spur. And there is the man.

"And people have talked about, 'Don't you think this is kind of grotesque to show these people at this compromised state? Is it a good idea to show these people withering away and dying?' And I think it is. I think it's a celebration of life to show the bag that's left, that once was, that did all these great things."

Herrington left Cassin in his chair by the window. Guido drove him back to the train station. As they were riding down into town, Herrington caught a glimpse in the distance of the Piz Badile — with its 800-meter wall of granite that Cassin and Ratti had scaled using their hemp ropes.

One week later, Herrington was in Tuscany when he got word that Riccardo Cassin had died.

So far as Jim Herrington knows, he'd taken the last portrait of Riccardo Cassin.

'It's Turned In To Be The Best Year Of My Life'

In the end, Jim Herrington took portraits of 60 men and women who climbed from the 1920s through the '70s. His goal was to get them published in a book. It wasn't easy.

Not long after he photographed Cassin, Herrington had a book deal fall through.

He was in such financial trouble that he had to spend a November night sleeping on a park bench in New York City.

But this past October — 19 years after he began the project — Herrington's first book, “The Climbers,” was published.

"To see people holding it and enjoying it — which I guess they are — it's turned in to be the best year of my life," he says. "And it's nice to be out seeing it ended. It's quite a relief, also."

And if you flip to page 162, you'll find Jim Herrington's portrait of Riccardo Cassin.

I asked him to describe the photo.

"I'm outside his house, and he has been parked by this open window — kind of a classic, old Italian house with the bigger windows that swing open," Herrington says. "And it's a dark room on the inside, and he's sitting in his chair and he's kind of coming out of the darkness. And he's looking out the window. And reflected in the glass are the Italian Alps — you can faintly see out of focus. And you know that's where he's looking."

This segment aired on December 2, 2017.