Advertisement

Retired Contractor Discovers Rare 1890 Players' League Documents

Resume

In March, Joe Tomasulo, the East Coast consignment director for the sports memorabilia auction house, Memory Lane, was in White Plains, New York, for the JP's Sports & Rock Solid promotion show.

He set up his table near the front door of the convention center — it’s his usual spot.

"A gentleman walked in with his wife, with an accordion file, said he wanted to show me some rare documents that he's held for many years," Joe explains.

Joe won't tell me the names of the gentleman and his wife. Like most of Joe’s consigners, they've chosen to remain anonymous ... for reasons that are also undisclosed.

"I'm being very vague here, but I think you get the point. It's a privacy issue," Joe says.

What Joe will say is that the gentleman is a retired contractor. And he acquired the documents on the job sometime in the mid-'90s.

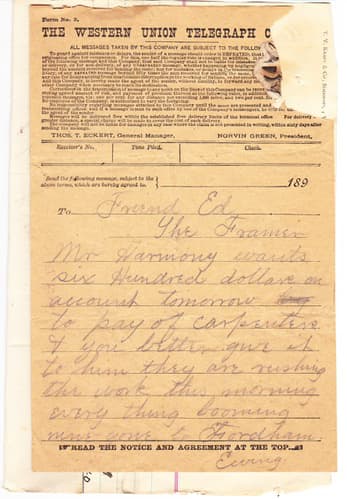

"They were unearthed from a desolate, New York office building — upstate New York," he says. "The wooden floors were termite-ridden. So they basically had to replace the floors with cement. There was a particular storage room with a bunch of boxes. So he just went directly to the owner of the building, 'What do I do with this stuff?' He told him to keep it, throw it out, do whatever you want. Just get rid of it. So he didn't have the time to go through all those boxes. He just took what he thought was interesting."

And the rest went into the trash.

"God knows how many historical signatures, documents were thrown away. Sad," Joe says.

'Autograph Collector's Dream'

Joe started thumbing through the documents.

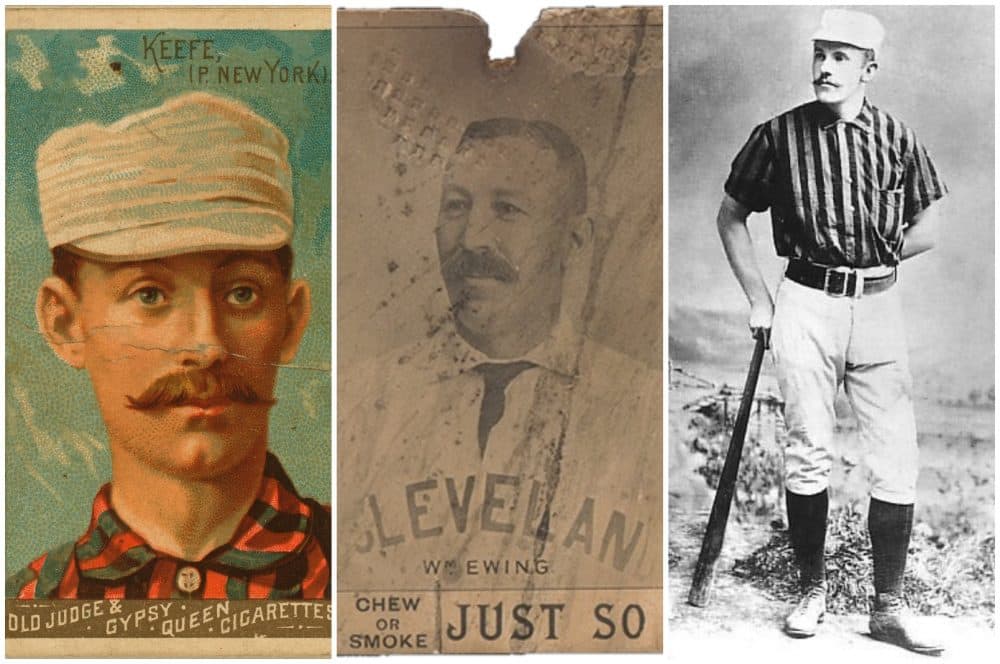

"And I'm seeing John Ward's name and Tim Keefe and Buck Ewing," he says.

These names were familiar to Joe Tomasulo. They’re very early Hall of Famers and some of the most sought-after autographs in the baseball world.

"This is a point I can't stress enough. There's a handful of those Hall of Fame signatures currently existing in the hobby," Joe says. "A couple of Keefes, a couple of Ewings. Maybe a few more of Ward, maybe four or five Wards.

"All I'm thinking to myself is, 'This is a dream, this is an autograph collector's dream.' "

But Joe noticed something else about these documents: the team names were from the 1890 Players’ League.

Joe had heard of the Players’ League before, but in all his decades of working in "the hobby," he’d never come across documents like these. He’s seen a couple of baseball cards, but that’s it.

"They're basically unique," he says.

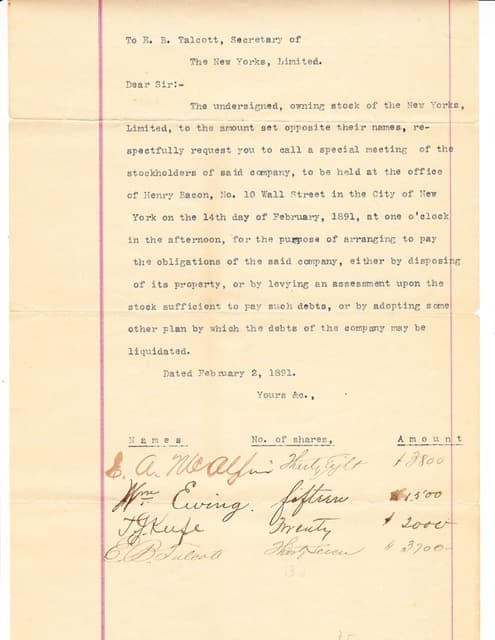

As Joe was thumbing through the pile, he came across one particular document — a single piece of paper dated Feb. 2, 1891 and signed by four shareholders of one of these Players’ League teams.

"I'm thinking to myself, the Queen Mary has pulled in," Joe says.

Joe’s excitement is monetary: he believes that document to be worth a lot of money.

But I’m fascinated by it because of what it represents.

The Reserve Clause — And The Brotherhood

"Going back to 1889, to make it simple, players back then were treated like mere sheep," Joe says.

"They were held to what was called the reserve clause, which meant that every season your contract would expire and your team would offer you a new contract," explains writer W.M. Akers. "And you could either sign the contract or you would be banned from baseball."

In the late 1800s, owners had all the control, and they knew it. They could pay their players whatever they wanted, fine them for anything — literally anything.

"There was one team that was almost insolvent, and so the owner started fining the players for every loss," Akers says. "And by the end of the season, he'd fined them so much that he was able to recoup their entire salaries."

Along came John Montgomery Ward.

"He's the only man in history to collect 100 wins and 2,000 hits," Akers says.

Ward wasn’t just a great player. He was also a really smart guy — he studied law at Columbia. And in 1885, he founded a secret society. He called it the Brotherhood of Professional Baseball Players.

"It's what today we would call a labor union, although they were very, very careful to avoid using that term, because it was pretty incendiary," Akers says.

Within a year, 90 percent of National League players had joined, and the Brotherhood went public.

"Ward's big target was the reserve clause, and he wanted to give his players the right to negotiate freely with what we would today call free agency," Akers says.

The owners were wary of the Brotherhood, at least at first. They made a few concessions, but then took them back.

Ward needed a way to get close to one of the owners — to bend his ear.

Another Setback For Athletes: Salary Cap

After the 1888 season, A.G. Spalding, owner of the franchise in Chicago, arranged for an around-the-world baseball barnstorming tour — to spread the love of the game ... and sell sporting goods.

Ward saw an opportunity.

"He felt like, 'Maybe, if Spalding and I are alone on a boat for several weeks, maybe I can talk to him, I can show him that, hey, the reserve clause is not good for us or for you. Let's move this game into the future together,' " Akers says.

So Spalding and Ward boarded a ship bound for Hawaii, Australia — then Cairo, Paris and London. But "three days after they set sail, the National League enacted what was called the Brush Classification Plan," Akers says.

The Brush Plan was essentially a salary cap. Players were "graded" from A to E.

Top players were Grade A, and under this plan, they would make $2,500, which was half of what they’d earned the year before.

Grade E players would make just $1,500. And, "if the owners wanted to, they could force a Grade E player to sweep the ballpark. That was very important to them," Akers says.

News of the Brush Plan didn’t reach John Montgomery Ward until months later, when Spalding’s barnstorming tour reached Cairo.

And if Ward was upset, he didn’t let the press know.

"Basically, he refused to comment. He sort of bided his time," Akers says.

When the tour reached Paris, Ward headed back to New York, telling Spalding and the press that he had some personal business to attend to.

"This was not a lie," Akers says. "He was married to a Broadway actress and his marriage was, kind of, falling apart. In addition, he went home to try to deal with his union and this salary cap."

The Brotherhood was furious. Many wanted to call for an immediate strike.

"Ward would say, 'Let's not do anything yet, let's not do anything yet, let's not do anything yet,' " Akers says.

What Ward didn’t say, at least at first, was that he had a much bigger plan to take down the reserve clause.

"This is when the players, after years and years of getting kicked around by ownership, really get to thumb their noses at them and say, 'That's it. You're not gonna hire us for your league, we don't care, we're done.' "

W.M. Akers

A Short-Lived Success: The Players' League

"Rather than do, like, a one-off strike now, which would really just poison the fans against him, he wanted to get together enough money to actually start an entire independent baseball league," Akers says.

So, every time Ward’s team went on a road trip, he’d meet with investors in major league cities. His pitch was simple: 'How’d you like to own a baseball team?'

Turns out, there was plenty of interest.

"So, on July 14, which is, happily, Bastille Day, they voted on a secret manifesto to declare, 'We have determined to play next season under different management,' " Akers says.

News of their "secret manifesto" leaked out, and soon everyone knew what was about to be announced.

"So it's Nov. 4, 1889, and the players get together at the Fifth Ave Hotel, which is the deluxe Manhattan society hotel," Akers explains. "And this is, in some ways, the high point of the entire experiment. Because this is when the players, after years and years of getting kicked around by ownership, really get to thumb their noses at them and say, 'That's it. You're not gonna hire us for your league, we don't care, we're done.' "

King Kelly, a slugger for Boston, showed up — according to newspaper reports — wearing a tight-fitting pair of imported trousers, a tall, silk hat and a beaver overcoat.

He stopped to talk to the press outside the hotel, and taunted the owners of his former team by saying, "'Listen, if you want a job next season, I'll give you a job taking tickets at the turnstiles,' " Akers explains. "And then he tells the reporters, 'Goodbye. I'm going inside to manipulate the wires that will startle the baseball world.' "

"Was that just bravado, or did these guys really think that this thing was gonna work?" I ask.

"I really — I think they did think it was going to work. And I wouldn't call it a doomed experiment from the start. I think there's a very, very good chance that the Players' League could have succeeded, mainly because more than half of the players in the National League jumped ship. And most of the top players came, including guys like Buck Ewing, Monte Ward, Tim Keefe."

The Players' League placed most of its teams in major cities where a National League team was already playing.

"And I think if things had broken the other way, we could be watching Players' League baseball every week instead of National League baseball," Akers says.

But things didn’t break the other way. To field competitive teams, both leagues poached players from a third league playing baseball in 1890: the American Association.

"You had three baseball leagues going and none of them could field a really top-notch team. So it was, sort of, like, there was too much baseball and most of it wasn't very good," Akers says.

The American Association folded. The Players’ League might have made it back for the 1891 season if not for Buck Ewing, the player-manager of the New York team.

"Both of the New York teams were suffering, so the Giants have a secret meeting for Ewing after the season ends. And they say, 'Look, this is bad for all of us. Why don't you just quit?' "

And that’s just what Ewing did. The two New York teams announced that they would merge and play in the National League. Soon, the other clubs followed suit.

"It fell apart extremely quickly," Akers says.

'I Couldn't Even Put A Price Tag On It'

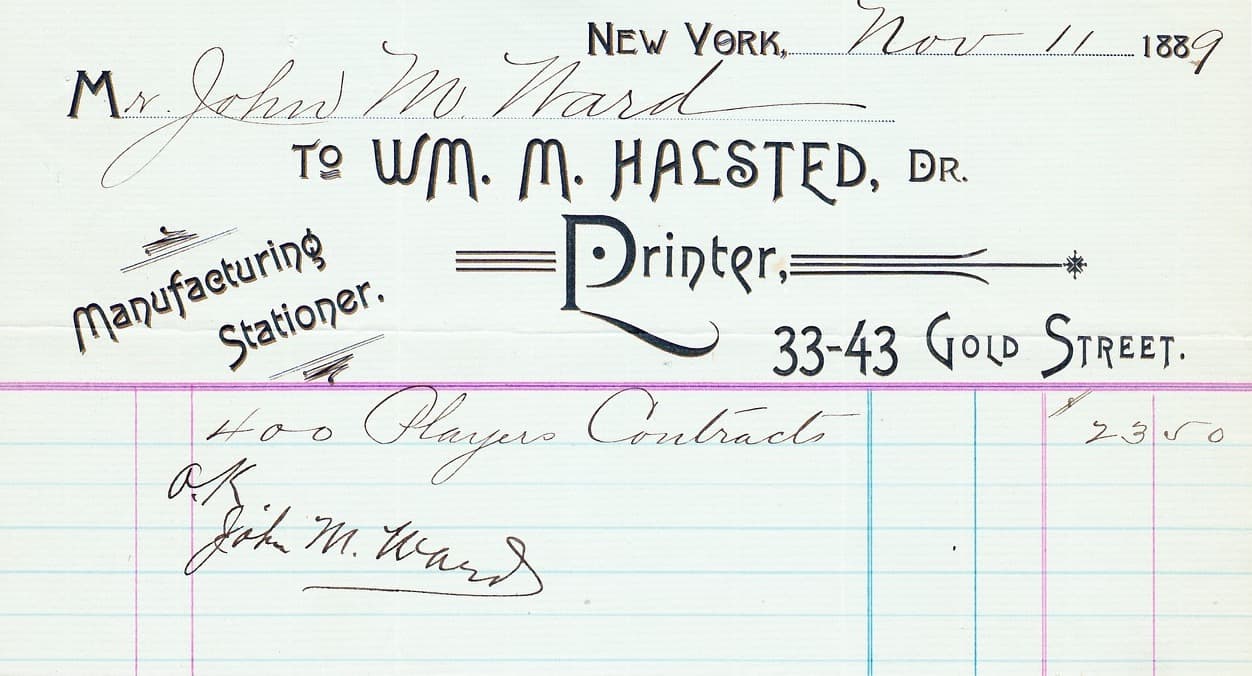

Much of this story is told through the documents unearthed in that upstate New York office building, from the unsigned draft of the league’s constitution, to the bill — authorized for payment by John Montgomery Ward — for the printing of 400 player contracts.

But then there’s Joe Tomasulo’s "Queen Mary": the letter signed by stockholders he’s hoping will fetch the highest price in Memory Lane’s upcoming auction.

That one was signed by future Hall of Famers Buck Ewing and Tim Keefe on Feb. 2, 1891. In it, Ewing and Keefe call for a meeting to discuss paying off the team’s debts, and acknowledge, as stockholders, that those funds would most likely come out of their own pockets.

But W.M. Akers says, that wasn’t the worst part:

"As soon as the Players' League died and then the American Association followed soon after, owners responded by taking full advantage of the reserve clause to slash salaries."

It didn’t work out for the Players’ League, but it just might work out for that retired contractor and his wife. Though, Joe Tomasulo didn’t tell them that right away.

"You know, you don't want to shoot for the moon right out of the gate," he says.

Joe says the document signed by John Montgomery Ward will likely go for $15,000 to $20,000. Tim Keefe and Buck Ewing’s signatures are worth more — maybe $25,000 to $50,000.

But what about the "Queen Mary" — that letter signed by both Keefe and Ewing?

"I couldn't even begin to put a price tag on it," Joe says. "I will say this, I would be disappointed if it fell anything less than six figures."

The consigners, that retired contractor and his wife, would probably be disappointed too.

"Did the consigners tell you at all what they planned to do with the money?" I ask.

"No," Joe says. "Other than, I think he had mentioned a couple of new kitchen utensils — they're redoing their kitchen. But other than that, no."

Memory Lane's auction opens Dec. 22, 2017. And you can find out more about W.M. Akers' baseball dice game, Deadball, here.

This segment aired on December 9, 2017.