Advertisement

Fahoum Siblings Advocate For 'Peace And Dignity' On And Off Tennis Court

Nadine Fahoum grew up on Mount Carmel in Haifa, Israel.

"It’s a beautiful city. My family and I lived on the mountain, overseeing the Haifa Port," she says. "Sunny, beautiful."

Nadine says she also loved Haifa because it’s home to Jews and Arabs who get along. She’s an Arab, a Muslim, a Palestinian and a citizen of Israel. She says that complex identity can present challenges, such as when she’s introduced to strangers.

"If I start with, 'I’m Israeli,' they tell me about their uncle’s bar mitzvah, and if I say 'I’m Palestinian,' they assume one thing about me," Nadine says. "And just saying both really confuses people."

'Meditation' On The Court

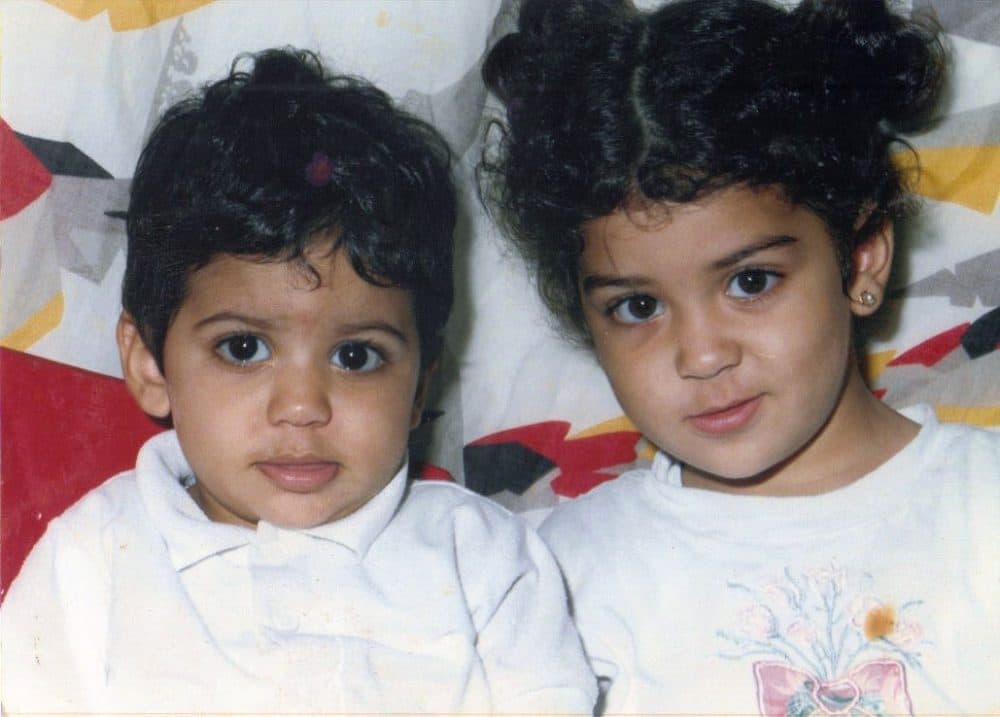

When Nadine was in first grade, her parents sent her to a private, Hebrew-speaking school in Haifa. She was the only Arab student there until her brother, Fahoum Fahoum, enrolled two years later.

"My parents wanted their kids to interact with the people they live with," Fahoum says. "They wanted to open us up to 'the other.' "

That happened. Nadine and Fahoum say they quickly made Jewish friends. Hebrew became their primary language. They usually felt safe at school. But there would be occasional confrontations when there was trouble in Israel, Gaza or the West Bank.

"I would hear things like, 'Oh, those Arabs, Palestinians, they should die. They want to kill us,' " Nadine says. "And I would say, 'You know, I am also Arab, I am also Palestinian and I don’t want that.' And they would say, 'Yeah, but you’re not like them.' "

"We got a lot of criticisms for that. 'Why is your Hebrew better?' That we were not as 'Arab' as them, which ... I don’t know even what that means."

Nadine Fahoum

When Nadine was 9 and Fahoum was 7, they joined the Israel Tennis Center in Haifa. At first, they were the only Arab kids. But they felt welcome. They fell in love with tennis and played for three or four hours every day.

"It’s you, the other person and the ball. That was my meditation, that was my peaceful place," Nadine says.

"That experience isolates you from whatever it is that’s going on in the world," Fahoum says. "Everything else does not matter."

"And my mom saw how much fun we were having, and how easy it was for all of us to get along," Nadine remembers. "And she went and talked to the head of the tennis center and said, 'Hey, maybe we should go to more Arabic schools and bring more kids. It’s a great environment for the kids to integrate and have fun and have this opportunity.' And that’s what they did."

Coexistence Program

That sowed the seeds for the Coexistence Program at the Haifa Tennis Center. Eventually, the program would reach 14 other tennis centers in Israel. Fahoum and some of his nationally ranked teammates traveled to the U.S. for fundraisers to support the program. When he was 9, he took a trip to Boca Raton with a group of teammates, most of whom were Jewish.

"A donor decided to host an event at his house, and that took place Friday afternoon," Fahoum says. "And after we all talked about the programs, he was planning on having a Kabbalat Shabbat."

That’s a Jewish ceremony to welcome the Sabbath. It culminates with the blessings over wine, or "Kiddush."

"The donor is looking at us and asking us, 'Would anyone on the team like to do Kiddush?' " he says. "Now everyone looks at one another, asks, 'Do you know how to do Kiddush?' 'I don’t know how to do Kiddush.' 'Do you know?' 'No, I don’t know.' "

Advertisement

But Fahoum did. He had learned it in grade school.

"I raised my hand, and I say, 'I’ll do it.' Then you see all these eyes turning to me — 'What? This 9-year-old Arab-Muslim Israeli is going to do Kiddush?' " Fahoum says. "So here I am, grabbing the microphone and completely owning the Kiddush, doing it from start to finish with no mistakes. People were ecstatic. They were laughing about it. They loved it."

But that sort of mutual respect wasn’t always easy to come by. One day, when Nadine was in ninth grade, she was walking with her friends outside their school in Haifa.

"And my brother was outside playing basketball. And he scored, and while he was shooting the ball, he fell back on another kid," Nadine says.

"And that escalated," Fahoum says. "That escalation led to him calling me names."

"And the kid called my brother, 'Oh, you f-ing terrorist,' " Nadine continues.

"'Terrorist' and 'jihadist,' and things that really hurt me," Fahoum says.

"My blood boiled," Nadine recalls. "I went to the kid. And I was, like, 'You never talk to my brother like this ever again.' "

The boy was punished. And he never talked to Fahoum like that again.

'Just Questioning Every Part Of My Existence'

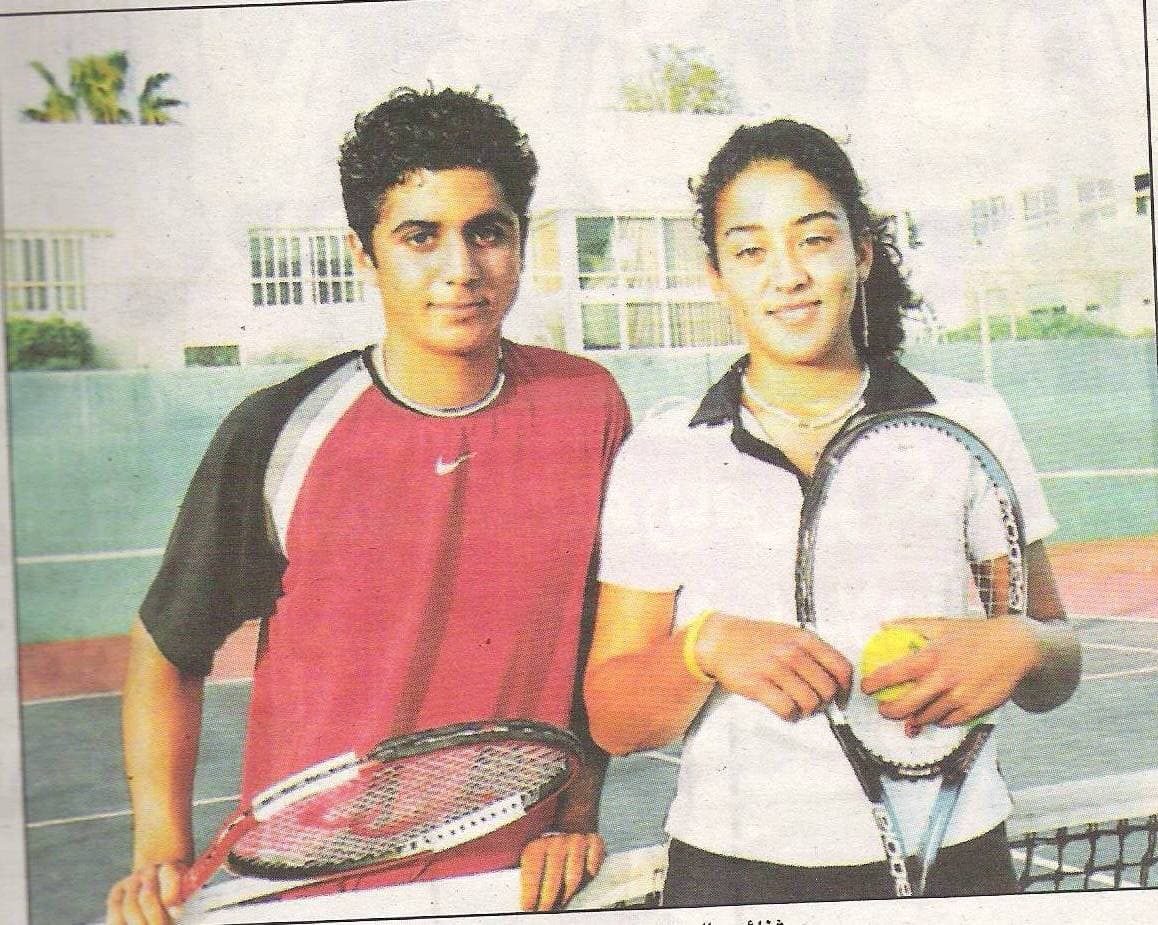

But Nadine and Fahoum wondered why anyone would label them that way. They represented Israel at international tournaments. Nadine was ranked No. 1 in the country, a ranking she’d maintained since she was 12. They were proud citizens. But not everyone accepted that.

"When I was 15, going to represent Israel in the Youth Olympics in Italy, I was just so excited that I got this opportunity, just wanted to go and perform and do my best," Nadine says.

The team gathered at the airport in Israel.

"And there were 40 athletes and about 20 more coaches, and I was the last athlete to go through security," she says. "And the security guy comes up to me and says, 'Hey, how are you?' And I say, 'Great, thank you,' in Hebrew. Perfect Hebrew.

"And he says, 'OK, great. Can I have your passport?' I say, 'Yeah, sure.' I give him my passport. And then he opens it and he sees my name, 'Nadine Fahoum.' Which is an Arabic name."

He told Nadine to wait.

"Five minutes later, he came back with another five security people, just questioning every part of my existence," Nadine recalls. "'Why is your Hebrew this good?' even — things that I was proud of. I was wearing the Israeli flag on my chest, and they knew I was going to compete for Israel. So it was very, very difficult for me, and the tears just flowing, couldn’t stop it. And I was just enraged. I was humiliated."

Nadine made it to Italy and became the first Arab-Muslim girl to represent Israel in the Youth Olympics. And, even though she admits she’s uncomfortable talking about it, Nadine says Arabs sometimes took issue with her as well.

"I got a lot of criticisms growing up when our Hebrew became better than our Arabic," she says. "We got a lot of criticisms for that. 'Why is your Hebrew better?' That we were not as 'Arab' as them, which...I don’t know even what that means."

"I think that if we can achieve a resolution where people can have peace and their dignity, we can move forward, you know, as a world."

Fahoum Fahoum

Fahoum dreaded the discrimination he’d sometimes face when he traveled to Arab countries.

"There was one tournament, for instance, in Jordan. I wanted to play it. So I signed up," he says. "But my application was rejected, which never happens. It’s unheard of."

Nationally ranked players had always been accepted at this tournament.

"And we started asking questions," Fahoum says. "We called the tournament director, and the tournament director bluntly said, 'We don’t want you to play this tournament because you’re an Israeli citizen.' "

Fahoum’s mother got involved, reaching out to the head of the International Tennis Federation and to Israel’s Minister of Education and Sport. Fahoum was eventually allowed to play. He reached the semifinals.

In 2008, on the occasion of Israel’s 60th anniversary, Fahoum received the honor of bearing a torch at a celebration on Mount Herzl in Jerusalem. Some in the Arab community saw that as a betrayal.

"But the way I saw it was that my work, my effort as an Arab-Israeli trying to promote coexistence between Jews and Arabs, was what brought me to that point," he says. "So, yes, there was criticism, but it never really affected me to a great extent."

'Peace Is What I Want'

After Nadine graduated high school, she attended Old Dominion University on a tennis scholarship. Two years later, she transferred to Duke, where she became the top player on the nation’s third-ranked team. She developed friendships with players from Germany, Poland, South Africa, Brazil and elsewhere.

"I really enjoyed the feeling of not being an Israeli, an Arab, a Muslim — I was just a tennis player," Nadine says. "And I loved it. And I didn’t talk politics for two years, and it was a very relaxing experience."

But there were questions from Jewish-American teammates about religious life.

"'What are the holidays?' 'Do you fast on Yom Kippur?' " Nadine recalls, laughing. "Yeah, all types of questions. Felt like an ambassador."

Fahoum went to Quinnipiac University on a tennis scholarship. He currently works in development at Yale. Nadine works in San Francisco at a private equity firm that invests in education and healthcare.

They consider themselves to be activists for peace, which often leads them to think of their native country and the people who live there.

"Jewish people need to feel safe in Israel, and the Palestinians need to feel safe as well," Nadine says.

"Peace is what I want. But I want people to have peace and dignity," Fahoum adds. "I think that if we can achieve a resolution where people can have peace and their dignity, we can move forward, you know, as a world."

Fahoum and Nadine play tennis from time to time. When she’s on the court, where it’s just the ball and the person on the other side of the net and nothing else, Nadine thinks about what the game means to her.

"Everything that I have today in my life, I got through tennis," she says. "Just meeting people on the court and connecting with them and doing bigger and better things with it later. Everything happened through tennis. I’m very grateful."

This segment aired on March 24, 2018.