Advertisement

As Evidence Of Brain Damage Mounts, College Football Grows. What's Next?

"I think a lot of us are the kids that might not quite fit in other places," says Christina Platt, president of the Penn State Outing Club. "You know, Penn State’s a big football school. Big sports school."

On fall weekends, when thousands of Penn State students are tailgating before games at Beaver Stadium, members of the outing club have often been miles away, backpacking in the woods of Central Pennsylvania or beyond.

That was going to be the plan for this year, too. Then last spring semester, Platt got a message from an administrator in the campus recreation department.

"Kinda just got this email," Platt says. "It was, like, ‘Oh, we need to have this meeting. It's an organizational review.’ "

For the previous year or so, there had been discussions about whether the outing club should fall under the university's club sports umbrella or under the umbrella of another department. So when Platt arrived for the meeting, she thought maybe the administration had finally found a permanent home for the club.

"I thought it was going to be a positive thing," Platt recalls. "They were just, like, ‘Well, you know, you're too risky to be a club sport. And you're too risky to be a normal recognized student organization. So you guys are dissolved.’ And we were like, ‘What?’ "

After a review of 79 student organizations, Penn State had decided that three clubs had “an unacceptable level of risk”: the diving club, the caving club — and the outing club. Platt could continue to do things like host speakers and film screenings — but leading organized trips was a no-no.

"I mean, we do strenuous hikes, but it's not like we're climbing cliffs or anything," Platt says. "We're just walking through the woods with backpacks. The real most dangerous thing is driving to the trailhead."

Advertisement

Penn State spokeswoman Lisa Powers declined our interview request. But in an email, she said the university had concerns about previous alcohol “misuse” and the distance of outing club trips from medical centers and cell phone service.

She wrote, “Penn State remains committed to the safety and well-being of our students.”

CTE Studies

But while the Penn State Outing Club was told to stay inside due to safety concerns, this fall tens of thousands of young men at universities across the U.S. — including more than 100 at Penn State — will be playing tackle football.

Ray Griffin hopes that they don’t end up like him.

"I have the mild cognitive impairment, which is the gateway to Alzheimer’s," Griffin tells me.

Griffin played football in the NFL and for Ohio State in the ’70s.

"I have tinnitus in my ears — the ringing in my ears," Griffin says. "And I also have, uh. Oh. What else is that? I have another one."

Griffin pauses.

"I did say mild cognitive impairment, didn’t I? Couple other things I just can’t remember at the time," he says with a chuckle.

Ray Griffin is 62 years old. He believes he's living with CTE.

"I know I am. The personality change, the outbursts of anger — I have all those things. I have all those symptoms," he says. "It makes it kind of lonely, to be honest with you. Because you don't want to be around people. I don't even have a lot of friends any more. Don't want friends. Don't care about having friends. I don't even hang around my family or anything like that."

CTE, or chronic traumatic encephalopathy, is a neurodegenerative disease that causes memory loss, mood swings and depression. It cannot be definitively diagnosed in the living.

But last year, the Journal of the American Medical Association published the results of a Boston University study of the brains of 202 former football players that found the disease was highly prevalent. It was a convenience sample — the brains were donated often because CTE was suspected.

Nevertheless, the results were striking: Out of the 53 former college players in the study, 91 percent had CTE.

'I Would've Rather Been Dead'

Ray Griffin grew up in Columbus, Ohio, in the ’50s and ’60s. He followed his older brother Archie to the hometown Ohio State Buckeyes and became a standout safety.

But during a spring practice junior year, Griffin came in to make a tackle on a fullback rushing up the middle.

"And I came up, made a hit on him," Griffin recalls. "And I was out cold. And I didn't even remember anything until probably the next day."

Griffin says that after that hit he started feeling depressed.

"I know that I was just living in a real, real bad funk," Griffin says.

But when fall came around, Griffin was back on the field for his senior season.

"And I'm tell you something, every hit hurt," Griffin recalls. "I mean, it felt like I was dazed. You get the headaches, things of that sort. Bright light — hurt your eyes. It was really bad. It was really, really bad."

But by the same time next Saturday, he was right back out on the field.

"You don't miss a beat," he says. "You don't miss a beat."

Griffin went on to play in the NFL for seven seasons. He says the depression didn’t go away. Sometimes he’d be driving and just start sobbing.

"So bad that sometimes I had to pull over and just cry," Griffin says. "I'll tell you, man, I had a couple times when I would've rather been dead. I'll be honest with you. I would've rather been dead."

"Once you get there, you just can't stop. That's why I will never ever own a gun."

Ray Griffin

After his pro football career ended in 1984, Griffin says he struggled to hold down a job. In 1993 he started getting treatment for his depression as well as drug addiction.

He says he’s now feeling better than he has in years. But Griffin still doesn’t feel well enough to spend time with friends and family.

"They have triggers that will just set me off," Griffin says. "And I mean, that's the reality of this disease. Once you get there, you just can't stop. That's why I will never ever own a gun. Because I know what can happen. I know I can lose it and just lose all control."

I asked Griffin whether he regrets playing football.

"I enjoyed the game," he says. "The game was good to me and good for me. But in the end it wasn't worth it."

'Scarce Males' And College Football's Growth

But even as more stories like Ray Griffin’s come out — and even as evidence mounts about the connection between head injuries and CTE as well as other diseases like Parkinson’s — the number of colleges offering the sport isn’t shrinking. In fact, it’s growing.

Even as evidence mounts about the connection between head injuries and CTE, the number of colleges offering football isn’t shrinking. In fact, it’s growing.

This fall, seven schools, from Maine to Arizona, are debuting teams. According to College Football Hall of Fame curator and historian Kent Stephens, there are now 776 colleges and universities funding football programs — the most there’s been since an accurate count started being kept more than three decades ago.

Why?

Here's a good place to begin to find an answer: across the country there are hundreds and hundreds of small private colleges that are known as "tuition-dependent institutions." These schools need full classes of paying students to keep their doors open.

"The pressures are very real when you're a tuition-dependent institution," says Maureen Devlin, a higher education consultant who previously served as executive director of the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics. "Any school that is in that position has got to bring students in."

And there’s one pretty big category of student that's becoming harder and harder to bring in: men.

Since the late ’70s, women have outnumbered men on college campuses — and the gap seems to be widening.

Today, U.S. colleges are approximately 56 percent female and 44 percent male.

College admissions officers have expressed fear that if their school becomes too lopsided, overall applications will drop.

So how does football come into this?

"That's a really good question," Devlin says. "Football, at least at the Div. III level, all of the teams that have been added — and more have been added than dropped in the 2000s — have been added for enrollment management purposes. And that is to bring in those scarce males and their tuition dollars."

Devlin says she see Div. III colleges with 110, 120 — sometimes even 135 — players on their football teams. And remember, this is Division III: none are on athletic scholarships.

In 2006, John Hill, then-athletic director at small Div. III Shenandoah University, told The New York Times, “You would be hard pressed to find five admissions officers or five professors or five marketing experts that could guarantee you 100 new, paying male students in one year. But you can hire five football coaches and they can do it. In fact, they can find you 200 if you want. Those boys just want to play.”

The 2,100-student Shenandoah University currently lists 114 players on its football roster.

The Resistance Part I: The Professors

As the number of colleges playing football grows, there are a few individuals on campuses who are fighting back.

One of them is University of San Diego history professor Kenneth Serbin.

Serbin grew up rooting for the Cleveland Browns.

"The original Browns," he clarifies.

But 23 years ago, Serbin was put on a path toward becoming a leader of the college football resistance. It happened the day after Christmas — when he learned his mother had been diagnosed with Huntington’s disease.

Huntington’s is a genetic disorder that causes nerve cells in the brain to break down. There is no cure.

Over the years, Serbin watched his mother become less and less like herself. In 2006, she died at the age of 68.

Children of someone with Huntington’s Disease have a 50-50 chance of inheriting the gene. Serbin was tested in 1999. He also has it.

"And I'm now 58 years old, and I'm at a stage where my mother already was debilitated by the disease," Serbin says. "And so every day for me is a blessing."

After his mother’s diagnosis, Serbin became an advocate for people with Huntington’s disease. He began studying the brain — and sharing what he learned on a new blog.

Then in 2012, something happened that was big news, especially in San Diego: former San Diego Charger Junior Seau had shot himself in the chest. It was later determined that he had suffered from CTE.

Serbin noticed similarities between the symptoms of Huntington’s Disease and the symptoms of CTE: anger, depression, memory loss — not to mention the burden both diseases placed on family members and caregivers.

And while there’s no way to prevent Huntington’s Disease, Serbin believed there was a way he could help people avoid CTE.

"As a university, we should not be endangering the well-being of students. And we do have a moral obligation."

Kenneth Serbin

He looked at his own university. The University of San Diego has fielded a football team for decades.

"As a university, we should not be endangering the well-being of students," Serbin says. "And we do have a moral obligation."

Serbin soon learned he wasn’t the only professor at USD who felt that way.

Nadav Goldschmied is a psychology professor. He was born in Israel, but came to the U.S. for grad school. He took an immediate liking to American football.

But Goldschmied gradually grew uneasy about the brain injuries associated with the sport. And then, eight years ago, he had a son.

"And I thought to myself, ‘There's no chance in the world that I'm going to let him play football,’ " Goldschmied says.

This sparked a very professorial chain of thinking.

"I thought, ‘Why wouldn't I accord the same protection that I accord my son to those in my community, and those in my immediate community?’ " Goldschmied says.

Goldschmied decided he should fight to get rid of football at USD.

"I think that people, to some degree, are entitled to do stupid things," he says. "The NFL can form their minor leagues. But, given what we know, I don’t think it should be played at the collegiate level."

Goldschmied teamed up with Professor Serbin and a USD physicist named Daniel Sheehan. They decided to do something that, as far as they knew, had never been done at another college. They were going to put forward a resolution to ban football at their institution. Not for budget reasons — but because they believed it was the right thing to do.

The resolution was to be taken up and voted on by faculty at the academic assembly.

Goldschmied knew it would be a tough vote to win — fighting the status quo is always hard. But he also knew that change can happen on college campuses. And, in at least one instance, a popular college sport had been brought to an end.

And it was because of faculty.

The Rise Of College Boxing

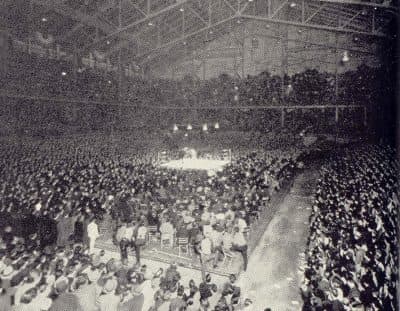

"It was an incredible scene," says Doug Moe, author of "Lords Of The Ring: The Triumph and Tragedy of College Boxing's Greatest Team."

"They would put chairs on the basketball floor and actually draw a couple more thousand people than they could for basketball. They had a band that would play before the bouts started."

Moe is describing a typical scene at the field house in Madison when the University of Wisconsin boxing team held a match.

Over 14,000 fans would come to watch the boys led by John Walsh, coach of Badgers from 1934 to 1958.

"One of the stories that Coach Walsh would tell was that a fire marshal once came up to him and said, ‘Look, I love college boxing, we're having a blast here. But you got way too many people in the field house — cut it back or we're breaking the fire code here,’ " Moe says.

After World War I, boxing had taken off as a varsity sport on the East Coast, eventually spreading across the country.

But the No. 1 college boxing team — the Alabama Crimson Tide of the sport, if you will — was the Wisconsin Badgers.

With Walsh as coach, Wisconsin won eight national championships.

But even back in the 1940s, there were people who believed boxing didn’t belong on college campuses.

In 1948, a Wisconsin economics professor made a motion to get rid of the sport, citing health concerns. The motion failed, but opposition kept growing.

In 1959, a college dean told Sports Illustrated, “If boxing is bad, it is worst for the men in our universities. Their brains must be good, and injury to such brains is a very serious matter.”

Supporters of the sport argued that college boxing built confidence and that it kept alive “an ideal of rugged fitness on which our country was founded.”

The Fall Of College Boxing

And then, in 1960, the Badgers hosted the NCAA college boxing championship. One of Wisconsin’s own fighters was looking to repeat as the national champion at 165 pounds.

His name was Charlie Mohr.

"Probably the most beloved guy on campus," Moe says.

Mohr helped out at a church. He once brought a panhandler to a team meal. Mohr told his coach, “I’ll pay for him.”

1960 was Mohr’s senior year, and he reached the championship bout against a fighter from San Jose State.

In the second round, Mohr took a hit.

"It was a punch to the side of the head — a strong punch to the side of the head," Moe says.

Mohr hit the canvas. The referee started the count. After two seconds, Mohr was back up. The fight resumed.

But then Mohr’s legs started to wobble. The ref called the fight.

"He walked back to the locker room under his own power," Moe says. "Sat down on a stool. And in very short order slipped off the stool and into coma, and was ambulanced to the University of Wisconsin hospital."

The punch had torn a major vein in Mohr’s brain. He was rushed into surgery. Mohr’s life — and some believed the future of college boxing — was on the line.

A three-hour operation stopped the bleeding and drained the blood, but tremendous damage had already been done to Charlie Mohr’s brain.

"He died eight days later on Easter Sunday," Moe says.

Soon after, Wisconsin political science professor David Fellman was having lunch with a group of colleagues. He mentioned that Mohr’s death was a shame.

"Another professor said to him, ‘Well, why don't you do something about it,’ " Moe says.

Fellman reportedly turned over his placemat and began writing a motion to abolish boxing. At the next faculty meeting, the motion was taken up.

It had been 12 years since the first attempt by a Wisconsin professor to ban boxing had failed. But after the death of Charlie Mohr, Wisconsin faculty voted to end the team. Soon after, the NCAA decided to discontinue boxing.

"And at that point, most varsity programs disbanded," Moe says.

A Vote To Ban Football

"Change is gonna come from faculty putting pressure," says University of San Diego professor Nadav Goldschmied.

Last fall, he and his colleagues Kenneth Serbin and Daniel Sheehan asked the academic assembly for the faculty of arts and sciences to ban football. It was a nonbinding resolution.

Many professors made arguments for keeping football.

"They were defending the values of the sport. The camaraderie and so on and so forth," Serbin recalls.

"Others said that, ‘If you play football it does not mean that you’re gonna get CTE — it just increases the likelihood,’ " Goldschmied says.

Then it was time to vote.

Fifty faculty members voted against the resolution. Only 26 voted in favor.

!["Given what we know, I don’t think [football] should be played at the collegiate level," USD Professor Nadav Goldschmied says. (Andy Lyons/Getty Images)](https://media.wbur.org/wp/2018/08/0824_oag_collission-1000x690.jpg)

"But — and this is important — there were 30 abstentions," Serbin says. "If those 30 abstentions had been in favor of our vote, we would’ve carried the day."

The University of San Diego opens its 2018 football season next Saturday.

Goldschmied now hopes that professors at other universities will pick up the cause. But Serbin thinks change will come from other places.

"I think what’s really going to happen is moms are going to stop their kids from playing football," Serbin says. "And I think that these colleges are going to face lawsuits. That is the one big thing that I think convinces people to change, which is when their pocketbook is damaged in some way."

The Resistance Part II: The Lawyers

Chris Dore is a partner with Edelson PC in Chicago. He says the law firm currently represents over 1,000 former college football players in more than 100 class-action lawsuits against the NCAA, conferences and universities regarding head injuries.

"The number is growing because we are continually contacted by people that are suffering from these issues," Dore says.

One of the former college football players who reached out to Edelson PC is 62-year-old Ray Griffin, the former Ohio State safety.

Dore says Griffin's story is representative of his clients.

"And there are many worse stories than Ray's," Dore says. "Ray has been through a lot, but I think he'd be the first to tell you that he knows people that are in a lot worse positions than he is."

Edelson PC argues that information about the long-term effects of head injuries has been available to the NCAA, conferences and universities for decades — and that not enough was done to protect athletes. The NCAA’s chief legal counsel has called the class-action cases “questionable” and said “the NCAA does not believe that these complaints present legitimate legal arguments.”

But could litigation — and all the costs that will come with it — actually bring an end to college football?

"No," says Michael McCann, Sports Illustrated legal analyst and associate dean at University of New Hampshire School of Law.

"The NCAA, I think, has accepted this as part of their business," McCann continues. "They're gonna be handling litigation on this front for years to come."

McCann believes football isn’t going anywhere at bigger schools like Alabama, Notre Dame and Florida. The sport is too profitable and too big a part of school culture.

"[But] if we're looking at smaller colleges that lose money on football and that will lose more money — not only because of payouts from litigation, but also higher insurance rates — it could prove meaningful," McCann says.

Universities pay for insurance to cover many things, including lawsuits. And with so much uncertainty over future concussion litigation, those insurance policies could become more and more expensive.

The Future Of College Football

All of that means the cost of running a football program could grow, and sponsoring football might not be worth it for the hundreds of smaller Div. III colleges across the country — even those that need more men to enroll.

"Schools will start to drop football," higher education consultant Maureen Devlin says.

Devlin thinks schools will drop the sport for a combination of reasons: cost, safety, the fact that football isn't a huge draw on some campuses, the decline in youth participation.

"The elite liberal arts schools that don't need football for enrollment management by any stretch — I think they'll be the first to start to drop football," Devlin says. "And that it may grow from there."

But Devlin still believes it will be years before that process gains momentum.

In the meantime, tens of thousands of young men from more than 770 colleges and universities will play football this fall.

And that number will likely grow: in addition to the seven new programs starting to play football schedules this year, at least five more schools are already planning to join the fray before 2020.

Next Saturday, Penn State hosts Appalachian State in its season opener. Penn State Outing Club President Christina Platt won’t be in the crowd. The Club recently received permission to go on day hikes within 50 miles of the university. Platt says her focus this year is on proving to Penn State administrators that her club can operate safely.

This segment aired on August 25, 2018.