Advertisement

'The Arm': A Story Of Anti-Soviet Protest From The 1980 Olympics

Resume

Let’s turn back the clock and go back to Moscow, 1980.

A little bit of background first: this story is about Poland. And Poland was never a part of the Soviet Union, per se, but was well within the area of Soviet influence and control. At the beginning of the 1980s, Poland’s economy was in decline. The country couldn’t pay its foreign debts, and its relationship with the USSR was strained — and would only get worse.

Meanwhile, the 1980 Summer Olympics were to take place in Moscow. But more than 50 countries had boycotted the games, including the U.S., Canada, China and Japan.

What was supposed to be a showcase for the Soviet bloc turned into a somber, grotesque spectacle. Athletes who had taken part in the previous Summer Games in Montreal couldn’t help but compare them.

"Montreal was such a beautiful event — but here, I couldn’t believe the Olympics could be such a nightmare," says Władysław Kozakiewicz, the legendary Polish pole vaulter who dominated the event between 1974 and 1982.

"We arrived at the village," Kozakiewicz says through a translator. "I looked around and, well … it was surrounded by barbed wire. It wasn’t like that in Montreal, but I thought, ‘Times change, terrorism and things like that.’ Security standards were much higher all over the world."

Kozakiewicz says an armed soldier even stopped him from visiting a friend who was staying in the building next door.

"The Olympic village is for athletes!" Kozakiewicz says. "What were soldiers doing there? Who were they defending us from — seeing how the village was guarded like an airport and they kept checking everybody all the time?"

So, the overall atmosphere of the Moscow Olympics was pretty stressful. And, for Kozakiewicz, there was a lot at stake. He’d broken his foot at the Montreal Games and failed to medal. Even though he’d won many major events over the previous four years, the fans at home were eager for him to bring back some Olympic hardware.

But the Soviets weren’t going to make it easy.

"I was incredibly stressed out," Kozakiewicz says. "We knew that they were obviously cheating, that they were doing everything to make sure the Russians won."

Kozakiewicz saw a Soviet long jumper awarded a fourth attempt even though he’d fouled three times and should’ve been eliminated. And, he says, in shot put and the discus, the judges were cheating, too — rounding up the measurements just for the Soviet athletes.

By the morning of the final, Kozakiewicz was a mess.

"I was so stressed I could barely talk," Kozakiewicz says. "I hadn’t slept, so in the morning I was like, ‘OK. I’m done with this. Sleepless nights are too much.’

"But that feeling only lasted until I entered the stadium. The moment I saw the packed crowds, it all just left. I was home. Finally, this was my place. The runway, the poles, the bar … oh, yeah! I wasn’t even interested in how others were jumping. I had my plan. I didn’t even take a warmup jump. I put my poles away and just waited to see what would happen."

When a pole vaulter is preparing for an attempt, the crowd is often silent. Sometimes, the athlete will encourage them to start clapping in rhythm.

Luzhniki Stadium in Moscow was nothing like this.

"Throughout the competition, the Russian fans in the stadium were whistling at us and jeering," Kozakiewicz says. "They booed every non-Soviet athlete and cheered only when a Soviet was up. They did everything they could to get under our skin."

And, as they’d done before, the Soviet authorities had made sure the audience was made up of … the right sort of people.

"Imagine, easily 70,000 people," Kozakiewicz says. "The stadium really was packed to the very last place. But in part it was because they were shipping people into the stadium — like from jail, prisons. Like, there was a whole section full of prisoners from some Moscow penitentiary.

"But I was so tough back then, all I wanted was to confront the Russians."

But despite the deafening boos and jeers, Kozakiewicz jumped into the lead.

"I cleared 5.65 meters on my first attempt," Kozakiewicz says.

That’s more than 18 1/2 feet.

"One by one, my rivals started getting knocked out," Kozakiewicz says. "The best four only cleared 5.65 on their third attempts. Seeing as I cleared it on my first, I’m leading the competition and feeling pretty confident."

Kozakiewicz had the lead, but his rival, Konstantin Volkov, had the support of the Moscow crowd.

"My anger was mounting as the competition went on," Kozakiewicz says.

With only four pole vaulters remaining in the competition, Kozakiewicz took his turn — and cleared the bar at 5.70 on his first attempt.

"As soon as I cleared that bar at 5.70, that was a gold medal," Kozakiewicz says.

Volkov had almost no chance to match that mark. Kozakiewicz knew it. And as he stood up from the landing mattress, he did something completely unexpected.

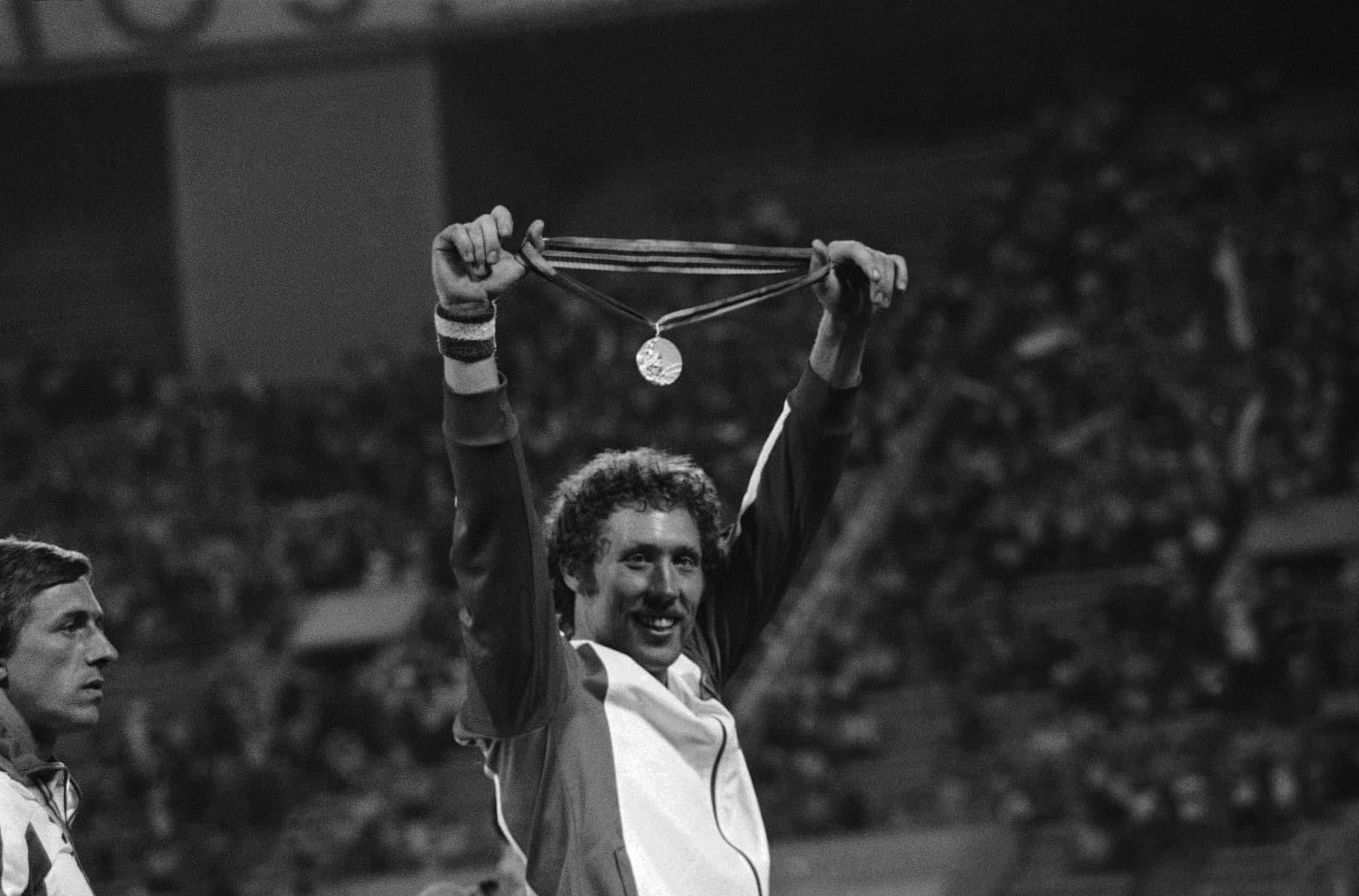

"I told them — I mean — I showed them ‘The Arm,’ " Kozakiewicz says. "You know what I mean. Put it in their Soviet face. Showed my anger for all their whistling."

The obscene gesture Kozakiewicz performed is sometimes called the Italian salute, the bras d’honneur, the Iberian slap ... or simply, "The Arm."

These Olympic games were supposed to represent friendship — a partnership among the communist nations. And Poland? Poland was supposed to be this quiet little nation that ought to be grateful to the USSR for being allowed to be a part of the glorious Soviet bloc.

And this guy stood up in the USSR’s capitol and showed a … let’s call it a 'regional middle finger' to 50,000 of its citizens. It didn’t look good.

Luckily for him, this was the 1980s. There were no Jumbotrons in Luzhniki Stadium. Much of the crowd didn’t even see Kozakiewicz’s gesture.

The competition went on. Kozakiewicz’s rivals failed to clear the 5.70 bar. From then on, there was only him and the world record. He asked for the bar to be set at 5.78 meters — just shy of 19 feet.

"My first failed attempt was accompanied by huge jeers and boos from the crowd," Kozakiewicz says. "Then I took the second jump — again, with them all whistling trying to put me off. And, well ... I broke the world record.

"When I landed on the mattress, I stood up and just didn't know what to do. I didn’t know what to do because I’d already done everything possible."

So, after lying on the landing mattress for several seconds, Kozakiewicz stood up and ... did it again. Nobody in the stadium seemed to notice. The event was over and Kozakiewicz returned to his apartment in the barbed-wired Olympic village.

"Later, I started realizing that I was probably the only person in the world — ever — who was being booed at while trying to break a world record," Kozakiewicz says.

Did he realize what he’d done, though?

"No — that’s the thing," Kozakiewicz says. "I did it because they totally deserved it. It just came completely natural to me."

Kozakiewicz didn’t intend to make any sort of political statement. Of course, the political context was there: Poles were often targets of Soviet propaganda for their political disobedience, and almost everybody in Poland was fed up with the whole Soviet bloc/Warsaw Pact situation. But Kozakiewicz wasn’t thinking about any of that. He simply, very emotionally, reacted to how the audience had been treating him.

Reality, however, soon made him realize what he had done. The very next day, the head of the Polish Olympic team took him to aside and said:

" ‘That gesture you did yesterday ... they want you disqualified, and your medal taken away,’ " Kozakiewicz recalls. "I looked at him. I couldn’t believe it. Take my medal away?

"If I’d shown everyone my butt or punched somebody, then I’d understand. But for this? I must’ve gotten to them."

The Soviet ambassador in Warsaw officially demanded Kozakiewicz be disqualified for life and his medal rescinded for "offending the whole Soviet nation." A disciplinary commission gathered and voted in favor of Kozakiewicz’s disqualification. He would lose the gold medal and his world record.

Then case seemed to have been irreversibly lost. But then, Juan Antonio Samaranch, the future chairman of the International Olympic Committee, ran late into that disciplinary committee meeting and intervened.

"Somehow, they annulled this vote and decided they weren’t going to take my medal after all," Kozakiewicz says. "I heard it was a real knife edge as to whether they were gonna take it or not."

Outside the sporting world, the incident took on a life of its own. Poland was on the brink of a social and political revolution, with its first major strikes coming in the following months. When Poles saw Kozakiewicz’s gesture, they loved how it showed defiance.

That arm became a symbol for the whole nation rising up against the Soviet Union. When Kozakiewicz came home, people on the streets wouldn’t let him pass — chanting his name, shaking his hand, hugging him, cheering him, tossing him into the air, even.

Suddenly, he was a hero, someone who had single-handedly stood up against tyranny — had won even — and had spoken for the whole nation. He became a symbol of resistance.

But for Kozakiewicz, the real trouble was only just getting started. The Polish Light Athletics Association, his employer, was still essentially controlled by the Soviet government.

"Back in Poland, thanks to that arm, they soon started disqualifying me from different events," Kozakiewicz says. "They would take my passport away sometimes, make me stay home. They even took my stipend money away.

"But, basically, I was jobless. They still wanted me to train and be in top form — but at the same time I wasn’t allowed to compete, and I wasn’t getting any money at all.

"Later on, I was just so sick of it all that I wrote them an official letter saying I was resigning from ever representing Poland at all."

In 1985, Kozakiewicz packed his car and drove to Hannover, West Germany — never to return to the People’s Republic of Poland again. He competed as a member of the Hannover Sports Club. And then, in 1986 he became a German citizen and started representing Germany.

West Germany was officially considered a hostile state to communist-ruled Poland, and Kozakiewicz’s emigration was regarded as treason. The home he owned in Poland was taken away, and the Polish communist authorities tried to use their leverage to stop him from taking part in competitions all over the world.

His exile ended in 1989, when Poland finally shook off Soviet domination. Kozakiewicz still lives in Germany, but he often visits Poland, where his protest at the 1980 Olympics made him a national hero.

"Speaking honestly, this gesture really helped me a lot in life," Kozakiewicz says. "It even showed me that I should move away. I know what I did gave other people a lot of happiness, showing that. And I’m proud I showed them — let them see that you can resist, in your own way. But it wasn’t heroic, and I still don’t think of myself as a hero."

And the obscene gesture Kozakiewicz performed in that Moscow stadium in 1980 — the Italian salute, the bras d’honneur, the Iberian slap or, simply, "The Arm" — went on to be nicknamed "Kozakiewicz’s gesture" in Poland. And that’s the only term people use for it.

This story was hosted by Adam Zulawski and Nitzan Reisner and written, produced and scored by Wojtek Oleksiak. It appears in the new season of Stories From The Eastern West, a documentary podcast about Central and Eastern Europe. More episodes can be found here.

This story appears on Only A Game as part of a special episode devoted to athletes and protest.

This segment aired on October 27, 2018.