Advertisement

Dancing Before The Nazis: A Soccer Star's (Supposed) Act Of Defiance

Resume

If you google the name “Matthias Sindelar,” you’ll find quite the tale.

"Pretty much the first five hits you’ll get talk about his defiance against the Nazis — often stories that come from really reputable sources," says Kevin Simpson, author of "Soccer Under The Swastika."

The stories usually begin on April 3, 1938 — just three weeks after Germany's annexation of Austria — when Nazi officials arrived at Vienna’s Prater Stadium to watch a soccer match.

It was an exhibition between the national teams from Germany and Austria. The idea was that the two sides would play a friendly game before coming together to form a single team for the 1938 World Cup.

Sindelar was one of the Austrian strikers who took the field that day.

"There's a story that the game was supposed to be a competitive draw to make everyone happy," Simpson says.

In other words, it was supposed to end in a tie. But in the second half, with the score 0–0, Sindelar scored. A teammate followed with another goal to make it 2–0.

And that, the stories go, is when Matthias Sindelar made his way to the center of the pitch — and staged his act of defiance.

"Danced a jig, essentially, in front of the Nazi elite who were gathered there for this match," Simpson says.

Some accounts even specify that Sindelar had a grin on his face as he danced before the box of Nazi officials.

A few months later, Sindelar declared he would not play for the unified German team. Instead, he was retiring from soccer.

Less than a year later, he was found dead.

The stories will tell you that perhaps the Gestapo killed him. Or that maybe he killed himself, unable to go on living in a Vienna ruled by the Nazis.

Just days after Sindelar’s body was found, Alfred Polgar, an Austrian-born theater critic, wrote:

“The good Sindelar followed the city whose child and pride he was to its death. He was so inextricably entwined with it that he had to die when it did. All the evidence points to suicide prompted by loyalty to his homeland. For to live and play football in the downtrodden, broken, tormented city meant deceiving Vienna with a repulsive spectre of itself. … But how can one play football like that? And live, when a life without football is nothing?”

"Certainly a beautiful sentiment, but we realize it just doesn’t match what we know," Simpson says.

Simpson doesn’t believe that Sindelar was murdered — or that he took his own life. And that’s not the only part of the popular Matthias Sindelar story that’s been called into question.

"If we look closer at the whole story, we have to say, most of it wasn’t really true," says Austrian researcher Georg Spitaler.

Spitaler believes Matthias Sindelar never was — nor intended to be — a Nazi protester. So who was he really? And if he wasn’t a hero, why has he been held up as one?

Austria, Coffee Houses And The Anschluss

Following World War I, Vienna was governed by the Social Democrats. But in the 1930s, fascism spread.

"Even if in the years between 1933 and 1938 in Austria, there was also a kind of Austrian fascism before the Nazis took over in 1938," Spitaler says.

Still, Kevin Simpson says there were places throughout Vienna that were largely free of fascism.

"The coffee house is the gathering place, almost like the salons used to be in Paris during the ’20s," Simpson says. "The intellectuals would gather there. The artists would as well. And they would’ve been very much aligned against the Nazi movement."

Politics wasn’t the only topic of conversation.

"You’d have this wonderful interplay of culture and ideas," Simpson says. "And it didn’t take them long to bring football into that discussion."

"The Austrian team was one of the best teams in Central Europe and on the continent," Spitaler says.

And Matthias Sindelar was the team’s star.

"He was quite thin and small, and that’s how he got his nickname," Spitaler says. "In German, it’s 'Der Papierene.' "

In English: The Paper Man.

Sindelar didn’t come from an elite, intellectual family. They immigrated to Vienna from Moravia. Sindelar grew up poor. His father labored in the brick works.

But Kevin Simpson says the people who gathered in Vienna’s coffee houses admired the way the Paper Man used his creativity to get the best of bigger and stronger opponents.

"Sindelar was routinely the one talked about," Simpson says.

Both Spitaler and Simpson believe Sindelar was a Social Democrat — or at least sympathized with the party — but Spitaler says the soccer star didn’t speak publicly about his beliefs.

And the real questions begin to crop up in March 1938, with the Anschluss — when Nazi tanks crossed into Austria.

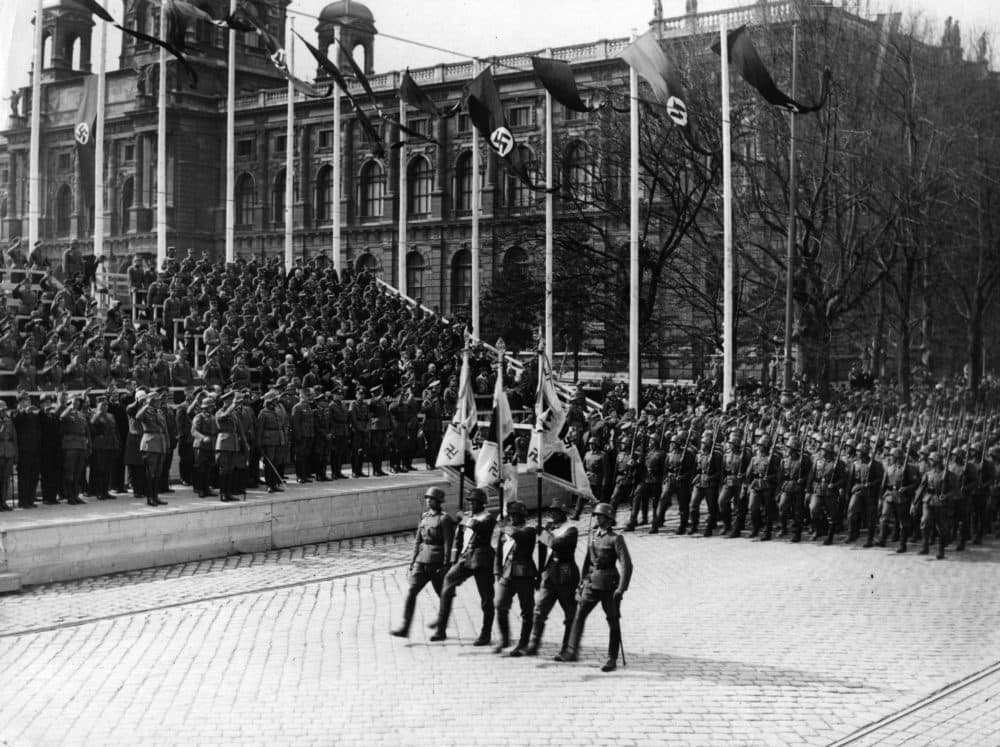

"The Austrian Nazis were lying in wait for this very event. So when it happens, the zeal with which they embrace Hitler and his associates even shocks those in Berlin," Simpson says. "And it didn’t take long for the banners and the swastikas and propaganda machinery to kick into effect."

Part of that propaganda machinery was the April 3 “reunification” match in Vienna between the Austrian and German teams.

Austria Vs. Germany

Matthias Sindelar netted the go-ahead goal. But as for that celebratory jig? Simpson says it happened.

"I believe that Sindelar danced in front of the Nazi elite. There is enough corroborating evidence from contemporaries and those who were maybe next generation," he says. "I believe that to be true."

But Spitaler isn’t so sure. He says that, based on old newsreel footage of the game, Sindelar didn’t seem to be acting out of the ordinary.

"It doesn't look different than any other celebration at the time, I think," Spitaler says.

There’s also a question about whether politics was the real reason Sindelar chose to retire rather than join the German team.

"I mean, on one hand, he was quite old for a football player at the time," Spitaler says of the 35-year-old Sindelar. "So we could suspect it had also, like, reasons that had more to do with his physical condition and less with political reasons."

And Spitaler says that if the Nazis were upset about any of Sindelar’s actions, they didn’t seem to show it. He says the Nazis helped Sindelar acquire a café that they’d taken from a Jewish man as part of “Aryanization.”

"If it was an act of resistance, the Germans didn't really care and tried to help afterwards with jobs," Spitaler says.

As for the soccer star’s unexpected death? Neither Simpson nor Spitaler find it likely that Sindelar killed himself or was murdered. They believe the official report that he died from a gas leak.

"A faulty heater was mostly likely the cause," Simpson says.

"Back in these days that was quite a common thing to happen," Spitaler says.

Kevin Simpson still considers Sindelar a heroic figure for his decision to retire rather than represent Germany — and Spitaler agrees that the soccer star at least behaved better than many Austrians.

But how did we get this tale that Sindelar was a Nazi resister who died for his beliefs?

Simpson and Spitaler first point to some of the coffee house intellectuals — the writers and artists who admired Sindelar and opposed fascism.

In addition to Polgar's obituary, Friedrich Torberg — another anti-Nazi Austrian writer who was in exile at the time of Sindelar’s death — wrote a poem called “Death of a Footballer.”

"Austria’s hands were dirty. And it makes sense that they’d want to push this history to the side by embracing this myth."

Kevin Simpson

"He kind of builds on this myth that Sindelar was a victim. That he was a symbol of old Austria kinda being killed by the new Nazi rulers," Spitaler says.

And that myth may have carried on after the war thanks to another myth out of Austria: that Austria was Hitler’s first victim.

"That was fed for decades after the war," Simpson says. "Some of it has to do with the unwillingness to acknowledge their contribution to the Holocaust. Austria’s hands were dirty. And it makes sense that they’d want to push this history to the side by embracing this myth."

Spitaler says the story of Matthias Sindelar — a soccer star who defied the Nazis — fits into that narrative quite nicely.

"His person was used by very different political groups, authors, journalists, especially after 1945, to build on this myth of Austrian victimhood. And he was a perfect symbol for that," Spitaler says.

"Are people bummed, though, when you tell them the more complex story about this guy who's been held up as such a hero?" I ask Spitaler.

"Yeah, sometimes they're disappointed, and I'm really sorry for that," Spitaler says. "But, still, for me as a political scientist, it's more a proof to the case that sports was so important for politics and still is. So I think it's a really interesting story with all the complexities. And this makes it a good story."

And it’s a story that’s endured.

Spitaler remembers turning on Austrian national television as a kid in the ’70s or early ’80s — decades after Sindelar’s death. And there on the screen was a well-known actor reading a poem. It was Friedrich Torberg’s “Death of a Footballer.”

This story appears as part of a special episode of Only A Game devoted to athletes and protest.

This segment aired on October 27, 2018.