Advertisement

Sharing Alex's Words: A Father Calls For Change After Daughter's Suicide

Resume

Richard Blackwell is a software engineer from Atlanta. Soccer referee. Father of two. Last September, in the middle of the night, there was a knock at his door. He was surprised.

"Who's not surprised by a pounding on their front door — an insistent pounding on their front door?" Richard says. "And then to look out and see the police are standing out front?"

This is probably a good time to mention that parts of Richard’s story are difficult to hear. It might not be for everyone.

One of those difficult moments happened as soon as Richard opened his front door.

"You know, ‘Officer, what’s going on?’ " Richard remembers. "He said, ‘Sir, do you have a 16-year-old daughter? If so, you need to check on her.’ And I left him standing at the door and raced up the stairs. I think I yelled ‘Alex’ as I ran up the stairs."

Richard’s wife, Kim, was right behind him.

"We got to her room. Her door was cracked, and her bedside lamp was on," Richard says. "And she was laying on her pillows asleep with her laptop open. Only she wasn't asleep."

Richard, Kim and the police officer started CPR.

"We knew the event for what it was," Richard says. "There was a letter laying on her bed. Of course, at this moment, we didn't have time to read that. But it was ... it was real clear what had happened."

Alex Blackwell

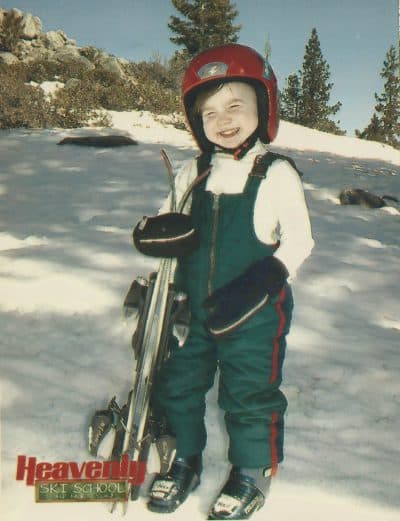

The story of Alex Blackwell’s life begins 16 years before it ended. She was Richard and Kim’s first child. And from a very young age, she had a lot of energy.

"She began walking at six months," Richard says. "She wasn't a big fan of sleeping, either. So at 4:30 in the morning, if Dora the Explorer came on, she wanted to be there watching it."

But when Alex was 2, her parents noticed something was wrong. Her legs were starting to bow.

"Like a cowboy on TV," Richard says.

Doctors diagnosed Alex with Blount’s disease, a growth disorder that causes the legs to bow out just below the knees. It happens sometimes with kids who walk early. To bring her muscles and bones back into alignment, doctors put Alex’s legs in braces.

"And she wore those for, gosh, probably a year," Richard says. "And she wanted out of them so badly. But she learned to run in them. She would go busting by — ‘clank, clank, clank, clank.’ Not unlike the movie 'Forrest Gump.' Forest Gump was the same thing.

"And when Alex came out of those leg braces, she was a speed demon. And that began her sports career."

Alex found herself at a disadvantage against taller girls in swimming and basketball. But she was just the right size for soccer. Her sister discovered the same thing — she’s two years younger.

"Alex was a bit of an introvert," Richard says. "Her sister, Grayson, is an extrovert. Both of them very sports capable."

Concussions

When it became clear that both of his girls were going to excel at soccer, Richard became a referee and started working his way up the ranks. That’s when he realized something that, in retrospect, gives him cause for concern.

"Soccer is a much more aggressive sport than I think a lot of people think," Richard says. "When you're on the field and you're not 100 yards away like the parents and the coaches, you see these things up close. And soccer is not unlike football in the type of contact that you have or hockey."

Alex’s first concussion didn’t happen on the soccer field. She hit her head on her friend’s open locker, fell down and hit her head again. She was in seventh grade.

"I'm not sure we saw anything that concerned us other than it was several months before we felt she was fully recovered," Richard says.

Alex’s second concussion came during the 2016 club soccer season.

"Alex was a center forward," Richard says. "And one of her favorite moves was to slide into the ball and crush it into the goal. But that's also sort of a backwards motion — just like sliding into home plate. She slid backwards and hit her head as she did. But at the time, we were at the game, it didn't seem remarkable to us.

"A week later, she had another match. Similar type thing. And she said it hurt when she hit. Again, it was unremarkable at the time. But later that night, she started having headaches. And the headaches were getting worse and worse and worse.

"So we took her to get her checked out, and they said that there appeared to be a prior injury of a week or two back. And Alex responded, ‘Yeah, I did hit my head and I was OK.’ "

The head injuries happened in the fall of 2016. And as the initial concussion symptoms — headaches, nausea, brain fog — started to fade, Richard and Kim noticed something they weren’t expecting to see: changes to Alex’s personality.

"Very subtle changes over weeks and months — that we believe began about the first of the year, about two to three months after the concussion," Richard says.

The Next Blow

Alex had always been an introvert. So at first, Richard didn’t think much of it. But it kept getting worse. She was fine hanging out one-on-one, but she felt uncomfortable when her friends wanted her to join them in groups.

"And it got to a point where she just stopped," Richard says. "She would just say, ‘No, I'm not going. I don't want to.’ "

Alex was diagnosed with mild depression and social anxiety. She was prescribed medications and started seeing a therapist regularly.

And then came the next blow.

"The Blount's disease turned back around, and she was beginning to have knee problems," Richard says. "And she needed to either quit sports or have the surgery. And we left that to her."

Alex had already decided that she wanted to be a doctor someday. Her future was academic, not athletic.

But Richard says she was looking forward to playing on her high school soccer team. They were expected to go back to the state championship. Alex wanted to be part of that.

So she chose surgery. Doctors told Richard that the procedure was nothing to worry about.

" ‘Oh, yeah, we're gonna saw her bone in half and twist her ankle around 10 degrees — and then we'll screw it back together, and it'll be fine. Nothing to it. We do it all the time,’ " Richard remembers. "But that's what they did. As it turns out, as you can imagine, there was a lot of pain associated with that."

Doctors operated on one leg and then the other, which meant that Alex was in a wheelchair or on crutches for the next six months.

Richard says Alex craved the endorphin release that comes with exercise. She longed to join her teammates on the field — and not just on the sidelines. And while doctors at the time did not connect Alex’s depression and social anxiety to the concussions she suffered, her father now knows they played a role.

"Looking back now with much more clarity, as best I can do just one year after the fact, there were a number of factors," Richard says. "I believe that if we could have taken any one of those out, we might not be having this conversation today."

'I'm OK, Dad.'

Late in the summer of 2017, Alex told her therapist that she’d been thinking about suicide.

"That becomes, of course, a red alert event for any therapist," Richard says.

Doctors quickly diagnosed the problem. They blamed a change in her prescriptions. They cited her lack of exercise and her eating habits.

"These were all things that they were very comfortable that they could adjust," Richard says. "And Alex was telling us that, ‘Yes, this is a big difference. I'm much better now.’ "

That brings us back to September 2017. Alex’s school was closed for a couple of days as Atlanta recovered from Hurricane Irma. Alex was at home.

"And I walked by her bedroom, and she was sitting on her bed with her laptop open and her headphones on listening to music," Richard says. "And she saw me walk by her door. And she pulled her headphones up, and I said, ‘You OK?’ And she says, ‘Yeah, I'm OK, Dad.’

"That was about five in the evening and the knock was around 1:30 in the morning."

Alex had been talking to her boyfriend on the phone. He’s the one who called for help. By the time Richard and his wife found her, she wasn’t breathing and had no pulse.

Richard and Kim performed CPR until the ambulance arrived just a few minutes later. Alex was rushed to the hospital. For two hours, Richard watched as a team of doctors and nurses tried to bring his 16-year-old daughter back.

"But they came to a point where they had exhausted every drug that they could give her," Richard says. "And the staff was physically exhausted. And just like that they looked up and ... there is nothing that prepares a parent for that moment."

'I Felt That I Needed To Tell This Story'

Richard says the sun was just coming up when he and Kim drove home. They were in shock. He doesn’t remember much from the next day.

"I think we dozed off a little bit during the night," Richard says. "But around 5 a.m., I just ... I couldn't lay in bed anymore. And I was beginning to feel this ... I say the word compulsion — a need to write down what happened. I felt that I needed to tell this story. Right now."

Richard sat down at his desk and wrote a warning to other parents. He was open about how Alex had died. He mentioned her concussions while playing soccer, and called for better protections for young athletes.

Richard gave his essay a title: “Is your daughter OK? Check again.”

He posted it on LinkedIn — he’s never been active on Facebook or Twitter. And a lot of people noticed.

"In some ways, I think it was therapy for me," Richard says. "But I also felt that Alex was nearby. And each time that I talk, including today, I reach out and ask her, ‘Alex, help me share your words.’ And I think she does."

Richard sometimes finds himself at his computer, unable to focus on work. That’s when he researches all the things he didn’t know while Alex was alive. He studies the link between concussions and mental health. He reads scientific studies on experimental treatments for depression. He advocates. He rallies.

Meanwhile, Richard’s younger daughter, Grayson, has choices of her own to make. I asked Richard if she still plays soccer.

"We don't know," Richard says. "She has not made it to a practice yet. Every Monday and Wednesday, she said, ‘I'm going to practice tonight, Dad.’ And each evening, some event comes up. So we're not sure."

When I first started talking to Richard, I thought this was a story about soccer — about how concussions are more prevalent than parents realize. About calls to limit headers. About whether head protection could help.

But soccer is only part of the story. Alex was a “speed demon.” There’s only so much that could have been done to keep her safe on the soccer field.

And as much as it seems like a story about suicide, Richard says it’s not that, either. He doesn’t talk about Alex’s death to raise awareness about suicide. He does it because he hopes to help people change the way they think about depression. Alex was embarrassed by the stigma of her depression diagnosis. She was embarrassed to be having thoughts of suicide.

But maybe she didn’t have to be? Maybe that is something that can be fixed?

So Richard shares Alex’s words. As often as he can. And by sharing the words of his daughter, who wanted to be a doctor, Richard Blackwell is starting to heal.

"I can laugh a little bit now that I couldn't six months ago," Richard says. "We are — we are so much better, and we're moving ahead. Because ... what else can you do?

"Well, I'll tell you what else you can do: you can recognize it for what it was and you can do everything you can to help other families avoid where we are today. And that's what we're doing."

If you or somebody you know might need help, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is available 24/7 at 1-800-273-TALK. That’s 1-800-273-8255.

This segment aired on November 3, 2018.