Advertisement

Migration And America: 30 Years Following A Filipino Family To Texas

With Kimberly Atkins

In 1987, Jason DeParle was a young American reporter for The New York Times, studying poverty in the Philippines. Through a bit of good luck, he managed to embed himself with a family living in a run-down shack in a shantytown built on a mudflat in Manila.

That good fortune turned into 30-plus years of friendship, as he followed three generations of one local family for a story on both the larger picture of global migration — from Manila to the Persian Gulf to the United States — and the more intimate look at what it means to become American.

Guest

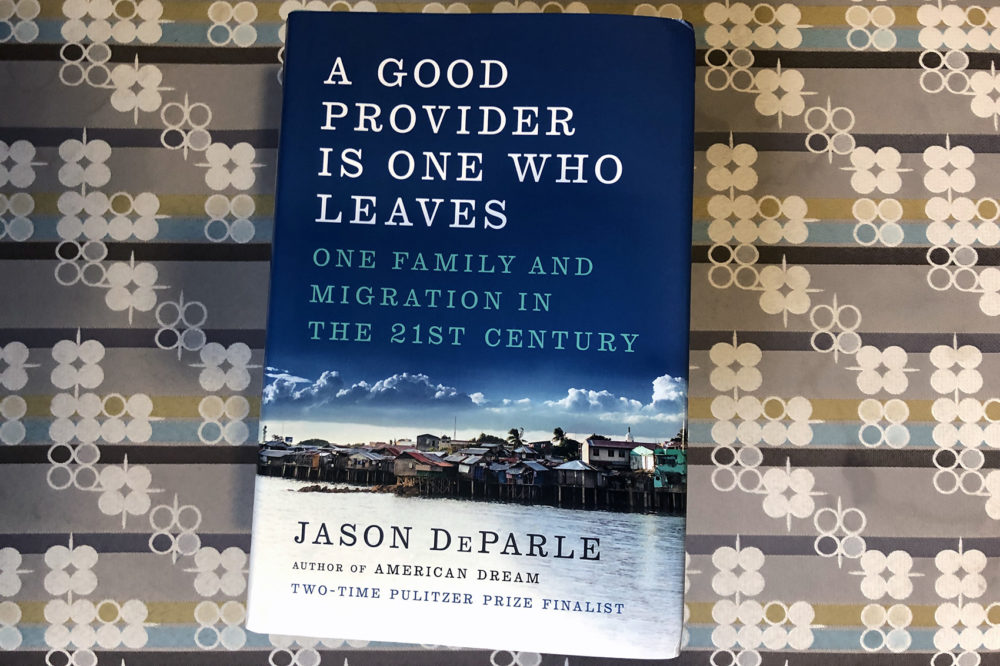

Jason DeParle, author of "A Good Provider is One Who Leaves: One Family and Migration in the 21st Century." New York Times reporter covering poverty and immigration. (@JasonDeParle)

Interview Highlights

On whether he was thinking about the broader issue of migration when he first went to report on the family in the Philippines in the 1980s

“I didn't even have migration in mind. I went to the Philippines because I was interested in slum life in the developing world, and I wound up moving in with a family, and it turned out that migration was how they survived. The father of the family was a guest worker in Saudi Arabia, and the mom was home raising their five children on the money he sent back. Over the years, all five of those children grew up and became overseas workers like the father. So, it was really only with the passage of time that I came to appreciate how important migration was to them and then of course to the world at large.”

On how he first discovered the Comodas family, who he would eventually report on for three generations

“I went to approach a nun, who lived and worked in this shantytown, and to try to persuade her to approach a family on my behalf. She was a little reluctant, but she finally agreed and told me to come back in a few days. I thought of course she would use the intervening time to discreetly raise the issue, and instead, she grabbed me by the hand and led me through the alleys and auctioned me off on the spot to the first a family that she [found]. So, the first woman — I knew just enough Tagalog to understand this woman was horrified — ... said, 'No sister, it's not possible.' And the second woman said the same thing, and the third woman was just too frightened to speak. Sister Christine had lost her patience by then and stomped off and said, 'If you don't want him, pass him on to someone else, and don't cook him anything special if he if he gets sick too bad,' and left me and this frightened woman staring at each other. I don't know which one of us was more frightened. And she eventually gave in to what she thought was Sister Christine's wish ... To let me move in, and out of that, a lifelong friendship developed. …

Advertisement

“I didn't know if I'd be there for a day, two days, if I'd be there at all. I mean, neither of us had any idea of what the plan was. There was no plan.”

On the family overcoming poverty through migration

“The oldest daughter in the family was born with a congenital heart defect and needed medicine and medical attention that the father couldn't afford. At one point, after years of worrying over his daughter, he dropped to his knees and asked God, 'Either take her with you up in heaven or let me have her.' This was his prayer: 'Help me help her, or take her away.' And God answered in a mysterious way a few days later with a job offer in Saudi Arabia at 10 times what the father, my friend Emet, was making in Manila. So, it would mean being apart from his family for two years, living in an Islamic autocracy, where stories of abused workers are rife, but it would multiply his family's income tenfold. So, it economically began a long lift and transformation of his family into the middle class.”

On how the book tracks the family’s transformation over multiple generations

“The book tells the story of three generations. And so, Emet, the father, was the part of the first generation. It was largely men going abroad to the Persian Gulf, particularly Saudi Arabia. In the wake of the 1973 oil embargo, the Persian Gulf countries were rich with petrodollars and short on workers, and they needed big building projects that were building roads and airports and hospitals and bridges, and the men went and did a lot of heavy construction work.

“In the second generation — which the main character of the book is Emet's daughter, Rosalie — migration feminized, and the migrants who were going abroad, particularly from the Philippines, were largely women going to do often caretaking jobs: domestic workers, nurses, nursing aides. So, the nature of the work changed and the migration changed.”

On Rosalie, one of the book’s main characters

“Rosalie was 15 years old when I moved in to the shantytown. She's now a 48-year-old mother of three and a registered nurse in Texas. If you were going to look around the shantytown, where 15,000 people lived, and pick the teenager who would be most likely to escape the poverty there, you probably wouldn't have picked Rosalie. She's very shy. She had no particular academic promise. She was a sort of C, B student. The thing that revealed Rosalie's character to me on her high school transcript wasn't her grades. It was her attendance. In four years of literal revolution and poverty — constant poverty in the Philippines — she never missed a day in class. She told me later on, 'About high school was when I got grit.'

“She's a four-foot, eleven-inch Filipino nurse, who would be the last person in the room you would tend to notice, and she has an enormous amount of resilience and strength. ... It took her 20 years to get to the states — an enormous amount of perseverance. She's worked in the Persian Gulf for 15 years, took the American nursing test three times, the English test five times. She just kept going.”

On what he thinks people could learn in reading about the Comodas family’s story

“Well, two things. I think the narrative right now is being dominated by discussions of illegal immigration, unauthorized immigration, and the crisis at the border — hugely important issues. But three-quarters of the immigrants in the United States are here legally, as Rosalie is.

“And secondly, I think President Trump presents immigration as a narrative of threat, that immigrants are a threat to our jobs, our fiscal budgets, our public health, our national security. And Rosalie didn't take an American job. She was recruited by an American hospital to fill a job it couldn't fill. A hurricane hit Galveston, Texas, closed down the hospital, and the hospital spent years trying to lure enough nurses back onto the island to fully rebuild the hospital. Only after years of frustration, when it couldn't find enough nurses, did it recruit abroad. So, she was one of 20 foreign nurses that came in and helped provide health care, improve the medical care of the community. In three years, her children not only learned English, lost Tagalog, wound up on the honor roll. They bought a house in the suburbs.

“There's a narrative in America I think that assimilation no longer works, that immigrants don't want to assimilate. Well, Rosalie and her family achieved in three years a degree of assimilation that used to take three generations, with a house in the suburbs and kids on the honor roll. So, no family can embody 44 million different immigration stories in the country, but I think hers embodies the story of immigration missing from the Trump Twitter feed.”

On President Trump’s rhetoric when talking about immigration

“I think there's a legitimate debate to be had about what kinds of immigrants, what mix of immigrant skills we need in the country, and that's a perfectly legitimate thing for America to be debating. I think where I'm troubled more by the president's rhetoric is when he talks about immigrants as terrorists, as criminals, as dangers to our communities.

“You know, during the campaign, he recited a parable of what he called 'immigrant treachery,' called 'The Snake,' where he likened refugees to snakes, who would turn around and bite the hand that feed them. The danger to assimilation I think doesn't come from a debate about what skill mix of immigrants we have in the country. It comes from a message that immigrants aren't welcome.”

On those who say immigrants have a difficult time assimilating in the U.S.

“I think there is a critique of immigration largely from the Right that holds that immigrants don't really want to be American, they're not adopting our civic values, they don't know our history, they're not patriotic.

“So, let me tell you a story. Rosalie and her kids were up this weekend with me, and we went to the Lincoln Memorial, and her daughters, who are 16 and 13, stood on the steps where Martin Luther King Jr. gave his 'I Have a Dream' speech and were able to articulate that Abraham Lincoln had freed the slaves. 'But they weren't really free,' these little girls said, 'because they weren't treated equally. And then Martin Luther King gave a speech 50 years ago about making them fully free.' And then they said, 'We as immigrants have inherited the benefits of that. We're the ones who benefit, because, thanks to Abraham Lincoln and to Martin Luther King, the country is more free or more open to people of all colors now.' You know, if that's not assimilation, my God, what more of a civics lesson would you want from young immigrants?

“I think American culture is a powerfully assimilative force in that immigrant parents often have a hard time ... keep[ing] it away from their children. Rosalie was determined that her kids would keep speaking [Tagalog]. She couldn't preserve that in a country where English is so powerful. … I mean, American culture was pouring in in their pockets, on their cell phones, in their schools, in pop culture. Whether it was stories about civil rights heroes at school or Hannah Montana at home, you couldn't keep American culture away from them.”

From The Reading List

Excerpt from "A Good Provider is One Who Leaves" by Jason DeParle

Hard Landing

The flight from Manila was bumpy and cold. Rosalie wore a parka and knit hat, looking bound for the Arctic, not Texas in summer, and snacked on cookies she called biskwits. Landing in Detroit, we proceeded to separate immigration lines. I found her at her second checkpoint, where a gangly agent was trying to capture her fingerprint. He loomed over her by a foot. “Relax,” he said, laughing, as she extended a digit stiff as rigor mortis. “Welcome to the United States.”

“For a long time I’ve been waited!” she said.

“You can work, you can travel, you can study.” The agent, who was African American, bristled at his final task: recording Rosalie’s race. “What is this, ‘Asian ... Caucasian’? Everybody’s the same—maganda!” Everybody’s beautiful.

“You speak Tagalog!” Rosalie said. Only a few words, but she appreciated the effort.

Her next encounter played out like a vaudeville routine. The Customs agent asked why she had come.

“For an employment,” she said.

“For unemployment?”

Rosalie beamed. “Yes! For my job!”

A flash of suspicion gave way to a laugh. He smiled and waved her Aalong.

Though Rosalie had spent twenty years thinking about the United States, everything about it seemed strange: the visa came without operating instructions. Stopping in Washington, we visited “the White Palace,” where the president works, and the Lincoln Memorial. She had never heard of Abraham Lincoln. A plaque marks the spot where Martin Luther King Jr. said, “I have a dream.” She had never heard of Martin Luther King Jr. She was surprised the planes did not serve mango juice. She was surprised to see no Filipinos.

The Washington suburbs, where I live, struck her as “quiet.” This was not a compliment. “Everybody’s busy with their own work. I think before you visit another person, you have to set an appointment.” She had been warned that Americans took independence to extremes—they sent away their children at eighteen!—and the do-not-disturb neighborhood vibe stoked her fears. “People are very liberated.” “Liberated” meant “alone.” “I think if I find a Filipino community, it will be good.” A few days later we flew to Texas, on another flight without mango juice. Rosalie pulled out a prayer kerchief with a Tagalog version of Psalm 91. (“He is my refuge.”) The interstate from Houston crosses Galveston Bay and opens onto an eyesore of fast-food joints and body shops; the GPS led us past a burned-out shack the size of a slave cabin. “Termites?” Rosalie asked.

She had rented an apartment in advance from the agency’s list. The manager was a cheerful beach hippie who suggested we eat at a “hole in the wall.” Rosalie looked alarmed. “Hole of the wall?” The manager advised her to get a roll of quarters for the washing machine. Rosalie did not know what quarters were, never mind a roll of them. The hole in the wall served poor boys. “Why not ‘poor girls’?” She called Walmart “Hallmark” and was paralyzed by the choices of crackers—dill, rye, sea salt, or olive oil? It was July, but Rosalie wore a sweater everywhere.

World travelers aren’t always worldly. Rosalie wanted rice with breakfast, lunch, and dinner. She was disappointed that the Golden Corral didn’t serve pancit, Filipino noodles. “A Filipino bakery!” she exulted, at the Mexican panadería sign. Rosalie had lived abroad for most of her adult life but always in Filipino cocoons. She had never seen a place where Filipinos were so scarce. After three days in Texas, she felt something going wrong. “I feel homesick.”

If the lack of pancit was one disappointment, the cityscape was another. “It is not a place you’ll be excited to see,” Rosalie said of Galveston. She had pictured the cityscape of Home Alone 2—Rockefeller Center and the Plaza Hotel—and landed in a luckless blue-collar town with 47,000 people and a vista of vacant lots.

Galveston was not designed “with habitation in mind,” wrote a native son. It’s a barrier island just three miles wide, in the center of a hurricane zone, and slowly sinking into the sea. The Indians had sense enough to stay on the mainland and make the dune a hunting and burial ground. The freewheeling Texans who followed had grander plans, lured by the harbor on the island’s coastal side.

The port made Galveston stupendously rich. By the 1870s, 95 percent of the state’s trade goods crossed its docks. Immigrants poured in—Germans, Russians, Scots, Czechs, and Poles—and merchant barons lived in European splendor. The city boasted eight newspapers, three concert halls, and an opera house, along with the state’s first medical school. Galvestonians like to boast that their forebears strolled gaslit streets when Houston was still a mud hole.

And then, devastation. The hurricane of 1900 remains the deadliest natural disaster in American history. It killed almost a fifth of the population—six thousand people—and destroyed half of the city’s buildings. While less determined (or deluded) city fathers would have fled, Galvestonians dredged the ocean to raise the town’s elevation and a good provider is one who leaves put up a seawall. But the glory was gone. Houston expanded its own port, and Galveston’s economic rationale disappeared.

Decade by decade, it withered. An empire of Depression-era speakeasies slowed the decline, and a downscale tourist trade endured. But the city’s population stopped growing in 1960 and fell 15 percent by the century’s end. Poverty rose. Once the grandest city between New Orleans and San Francisco, Galveston today isn’t even the largest in the county—just a humid curiosity with a silty beach. Some glorious old architecture remained, and the city kept the University of Texas Medical Branch, the research complex that grew up around the medical school. But while immigrants generally look to the future, Galveston “knows its future can never equal its past.”

In 2008, another hurricane hit, with Katrina-like consequences.

Galveston’s seawall faced the Gulf, but Ike’s storm surge attacked from the opposite side and swamped the island. Eighty percent of the homes were damaged. Sixteen percent of the residents never returned. With marooned boats littering its lawn and dead cows on the helipad, UTMB, the county’s largest employer, suffered more than $700 million of damage. The emergency room closed for nine months. By the time it reopened, hundreds of nurses had left for other jobs.

They weren’t easy to replace, given the island’s forlorn state and competition from Houston’s renowned hospitals. UTMB recruited from as far away as Nebraska and Florida, with signing bonuses of $5,000. But the best nurses wouldn’t come, and others wouldn’t stay. “We just can’t keep them here,” complained Chelita Thomas, a nurse manager.

“And the ones we get here, they’re not good. They’re absent all the time. They’re tardy, they’re lazy, they fight.”

Four years after Ike, patients were still backing up in the emergency room due to the shortage of beds. The hospital was building a new ward and needed nurses to staff it. UTMB had a nursing school, and faculty wanted jobs for their grads. But David Marshall, the hospital’s head nurse, said that he couldn’t safely staff a ward solely with new nurses. He had worked with Filipinos and admired their skills.

“I thought maybe the international pipeline was a way to get some experienced nurses here,” he said.

Rosalie arrived in the second of three groups, each about a month apart; they totaled twelve Filipinos, six West Indians, and a child of Cambodian refugees from Montreal. Except for the Canadian, they came from poor countries, but most had already been working abroad, in cosmopolitan hubs like London and Dubai. They agreed with Rosalie that Galveston was “not a place you’ll be excited to see.” One cried at first sight. Another vowed to finish her two-year contract in Galveston and then “move to the United States.”

But Rosalie was happy to be part of a group, even if the group was unhappy. At her first Mass, the scripture conveyed Jesus’s command to go forward with nothing but sandals and a staff and cure the ill. She felt she had obeyed. “I left and let God handle everything. I know God has a good plan.”

From the book A GOOD PROVIDER IS ONE WHO LEAVES by Jason DeParle. Copyright © 2019 by Jason DeParle. Excerpted with permission by Penguin Random House.

New York Times: "When Providing for Your Family Means Leaving It Behind" — "In 1987, a young American reporter looking to write about life in a Philippine shantytown met Tita Portagana Comodas, a local matriarch who grudgingly agreed to rent him floor space in her shack on a mud flat near Manila Bay. That reporter, the veteran New York Times journalist Jason DeParle, stayed with Tita intermittently for eight months, developing a friendship with her and her family that spans 30 years and three generations.

"It is the Portaganas who anchor DeParle’s new book, 'A Good Provider Is One Who Leaves,' a sweeping, deeply reported tale of international migration that hopscotches from the Philippines through the Middle East, Europe and eventually the United States. In some ways, it offers a mirror image of DeParle’s first book, “American Dream: Three Women, Ten Kids, and a Nation’s Drive to End Welfare,” which looked inward at the United States and the connections between domestic migration, poverty and welfare. 'A Good Provider' picks up on these themes, turning its gaze outward, toward the forces behind global migration.

"The phrase 'mass migration' conjures images of children crammed into holding centers at the United States’ southern border, or of refugees fleeing Syria and Congo, but the story of human movement is a far more complex one, full of contradictions and on a scale so vast that it is hard to comprehend. The World Health Organization puts the number of people living outside their native countries at 258 million, an increase of nearly 50 percent over the last two decades. And yet, when politicians talk of 'global markets' they are typically referring to the goods and services that flow across oceans and continents. Often ignored are the humans who flow over these same borders — the very people who drive the economies of the 21st century."

Boston Globe: "Jason DeParle offers an immersively reported reflection on contemporary migration" — "A young reporter in Manila wanted to live as a Filipino, preferably in a slum. A 40-year-old woman was willing to take him in. Thus began the education of New York Times reporter Jason DeParle, thus began a decades-long friendship, and thus began a remarkable book.

"The United States has 44 million immigrants — more than the entire population of Canada and, as DeParle tells us, 'it’s no exaggeration to say their future is America’s.' But migration also shapes countries around the world, the places migrants leave as much as the places where they settle, often temporarily, sometimes permanently.

"'Migration is to the Philippines what cars once were to Detroit: the civil religion,' DeParle argues. More than a million people leave the country every year, and in examining the phenomenon at close range, DeParle himself was transformed from journalist to student of migration. 'I wasn’t thinking about migration when I arrived in Leveriza,' he writes of his perch in the Philippines. 'I was thinking about rats and eggs, about people...endure such hopeless poverty. Migration was part of the answer.' "

Minneapolis Star Tribune: "Review: 'A Good Provider Is One Who Leaves,' by Jason DeParle" — "This ambitious and successful book profiles an extended Filipino family inching toward prosperity by laboring out of country for years, migrating to do arduous work in harsh places. It’s the opposite of an instant book; it has been cooking for three decades. The chef has combined, in considered proportion, ingredients gathered around the world — revealing family and work scenes set in the Philippines, Oman and Saudi Arabia, aboard wandering cruise ships and deep in the heart of Texas. And right when we’re hungry for them, he serves up telling social and economic digressions that place the family’s struggles in a political and economic context of global migration.

"Author Jason DeParle, a New York Times reporter, writes in the prologue to 'A Good Provider Is One Who Leaves': 'My own light bulb moment came in learning that remittances — the sums migrants send home — are three times the world’s foreign aid budgets combined. Migration is the world’s largest antipoverty program, a homegrown version of foreign aid.'

"This is a huge topic that looms in the lives of his subjects, but it is out of sight for many American readers, some of whom these days are systematically fed disinformation about migrants. DeParle has found a way to humanize and clarify this vast and complicated subject."

Hilary McQuilkin produced this hour for broadcast.

This program aired on August 28, 2019.