Advertisement

What Does It Really Mean To Get A Good Education?

Check out our four-part series on the achievement gap in American schools here.

Here’s something we thought a lot about during our September education series about solutions for closing the achievement gap — what does it really mean to get a good education?

College and career preparation are high on the list. But is academic accomplishment the only goal? Or, do we expect schools to impart other skills needed to thrive in adulthood, such as how to work well with others, or openness to new ideas — skills that not only help individuals succeed, but also make society better as a whole?

On Point recently visited Springfield Renaissance School, a middle- and high-school in Springfield, Massachusetts, a city of 150,000 people about two hours west of Boston. Springfield Renaissance opened in 2006, and was named for a planned “renaissance” of its home city, which, like many American cities, suffered a sharp decline in manufacturing-related jobs and an accompanying decline in income in the last decades of the twentieth-century. In the 13 years since, the school has swelled to about 700 students, and attracted national recognition for raising the achievement of students from low-income families and students of color. Like Springfield itself, the school is racially diverse. A little more than half of the students are Hispanic, about a quarter are Black and 19% are white. Students enroll via lottery. The school always has a waiting list.

A glance at its statistics explains why. Nearly 95% of students graduate on time, a rate nearly 20% higher than the district as a whole, according to 2017 figures, the most recent available from the Massachusetts Department of Education. The school’s passing rate on the standardized tests are also better than the state as a whole. Academic expectations are high. Nearly 63% of high school students complete and advanced course for college-credit, compared to less than 40% district-wide. Bulletin boards plastered with information about colleges adorn the hallways.

"It’s not just about making sure our students sit and do well on a performance assessment. It’s also, 'Are they ethical thinkers?' "

Springfield Renaissance School principal Arria Coburn

Principal Arria Coburn is proud of those stats. She emphasizes that mastery of knowledge — one of the measurements of which is Massachusetts' standardized tests — is paramount to the school’s mission. But it’s not the school’s only priority, she said.

“It’s not just about making sure our students sit and do well on a performance assessment,” Coburn said. “It’s also, ‘Are they ethical thinkers?’ ”

Renaissance senior Colleen Curley has received that message loud and clear. She’s been at the school since she was in sixth grade. She’s at the school because she wants to go to college, and she knows that Renaissance will get her there. Her older sister graduated from the school, and is now studying chemistry at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. College is important to Colleen’s parents, too: Her mom is a paraprofessional at an elementary school, and recently went back to complete her college degree.

But here’s how Colleen defines a successful Renaissance graduate: Someone “who’s a good person, inside and outside the school.” She cited her experience as captain of the school’s soccer team. They didn’t win a lot of games, she said. But they did win the sportsmanship award for the entire league.

“Renaissance is a part of who you are,” she said.

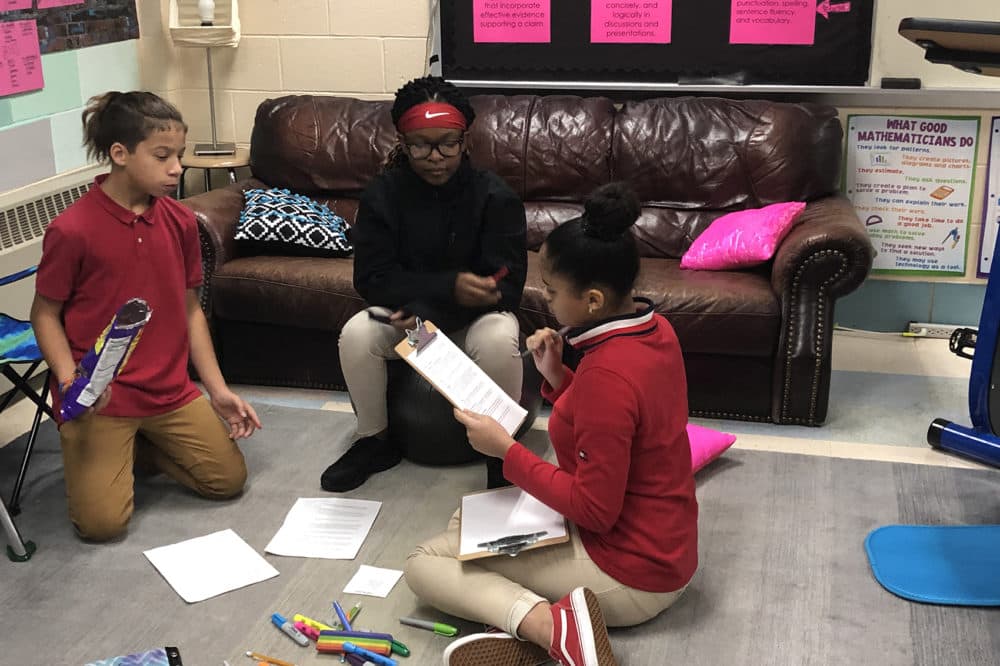

Springfield Renaissance students spend a lot of time in supportive peer groups learning social and emotional skills. Posters celebrating school’s community commitments — to friendship, perseverance, responsibility, respect, self-discipline, cultural sensitivity, and courage — are at the front of nearly every classroom, and hang on banners throughout the hallways.

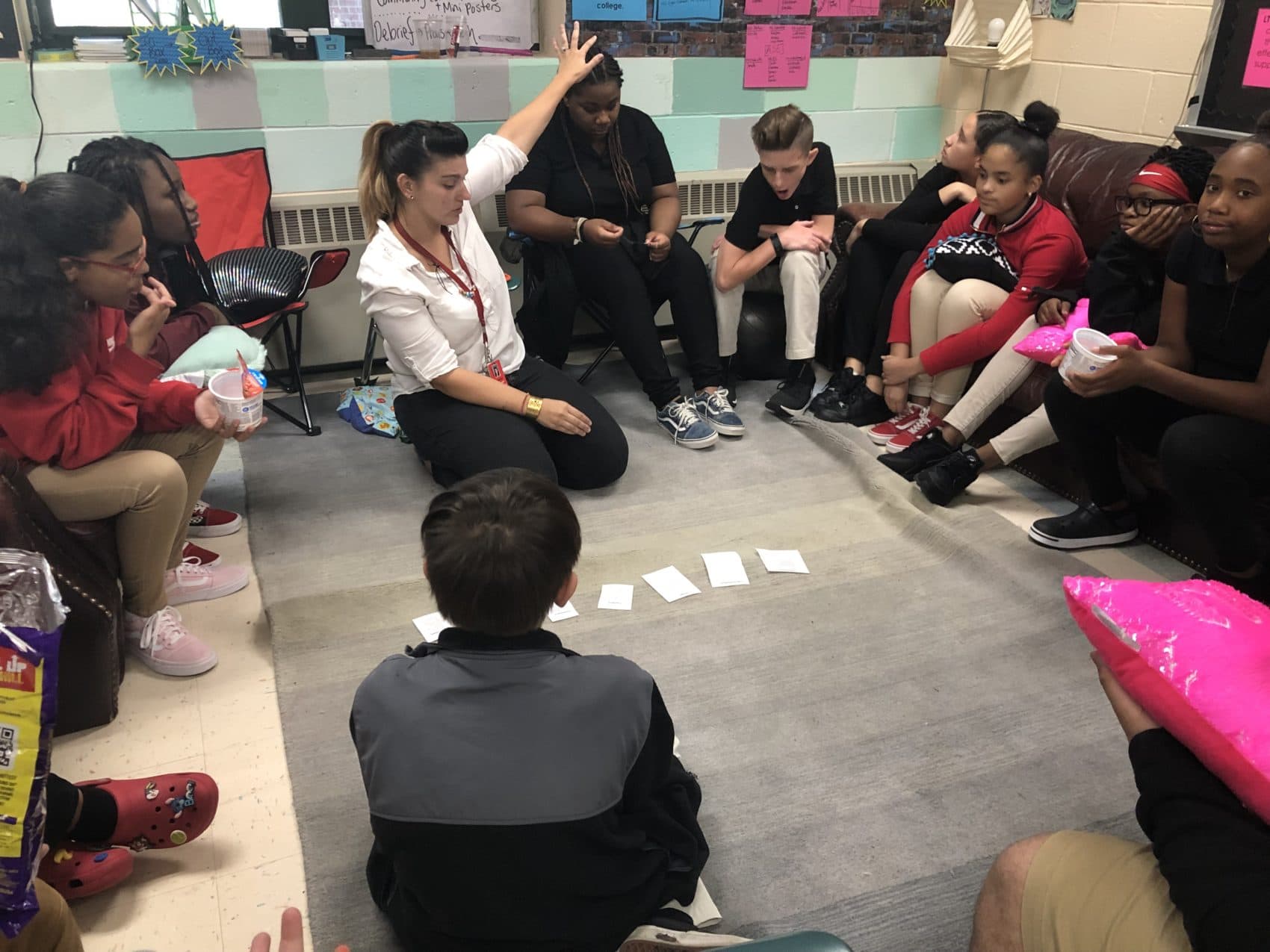

Students also spend time in “crew,” three times a week, a kind of “school family,” where they might complete homework but also check-in about the emotional highs and lows of the week and work on team building activities. The goal, Coburn said, is for every student to feel like they are known on a personal level.

In a seventh-grade “crew” class that On Point visited, students were talking about applying Renaissance’s community commitments to group discussions while lounging on bean-bag chairs and snacking on Takis.

Samantha Vega started as the seventh graders’ crew teacher last year, when they entered the school, and will continue on with the same group until they move onto high school, the idea that they’ll all form a tight bond and can serve as a tight-knit community-within-a-community.

“Kids learn best when they have a relationship with somebody,” she said. “Being able to create these groups of kids who might not necessarily hang out outside of this group ... and being able to have me as someone to support them through their middle school experience, really helps them with their self-image, helps them with their confidence, helps them with their ability to grow.”

A growing body of research on “social-emotional learning” — learning focused on the skills required to advocate for oneself and others — bears this out. Students learn better, and score better on tests, when they feel supported in school, and have explicit guidance and skills on regulating their behavior and recognizing how it affects themselves and others. They’re less likely to get distracted or to distract others, and that translates into academic gains. There’s an economic argument for focusing on social-emotional learning in schools, too: Interpersonal skills are also increasingly sought after by employers.

"Kids learn best when they have a relationship with somebody."

Springfield Renaissance teacher Samantha Vega

But the academic argument for social-emotional learning is not the only argument, Vega said.

Students at Renaissance are “learning how to work through being stressed, or how to ask for help” — things they’ll need in the real world as much as vocabulary and formulas.

“Kids can do way more than we give them credit for,” she said.