Advertisement

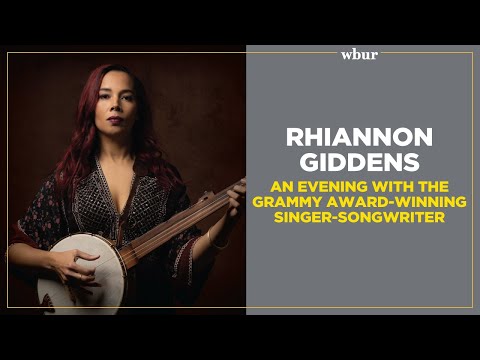

Musician Rhiannon Giddens digs into American roots music and finds connections to cultures around the world

Resume

Pulitzer Prize-winning musician Rhiannon Giddens digs deep into American roots music and finds connections to cultures around the world.

Can any culture lay total claim to specific styles of music?

Today, On Point: A conversation with musician Rhiannon Giddens, recorded live at WBUR's CitySpace.

Guests

Rhiannon Giddens, Pulitzer Prize winning folk singer, songwriter and multi-instrumentalist. Her new album "You're the One" comes out August 18th. (@RhiannonGiddens)

Transcript

MEGHNA CHAKRABARTI: Musician Rhiannon Giddens is on a quest. And the facts of her own life are a compelling metaphor for the path she's forging. Born in 1977 to a Black mother and a white father, Giddens' childhood in Greensboro, North Carolina was one where the messiness of American history showed, in how racial confines were both rigid and permeable.

She tells a story about how her Black grandfather and white grandmother both worked at a Greensboro tobacco factory. And once when her white granny, as Giddens calls her, needed assistance with her taxes, she went to Giddens' Black grandfather for help. "It's the South, isn't it?" Giddens told the New Yorker magazine.

"The point is that they are different, but the same." It's that duality that Giddens is exploring in the history of American music. She's already well known in Roots music as a former member of the Carolina Chocolate Drops. But more recently, she's been digging deeper into ideas about the rigidity and permeability of the cultural confines we place around music.

"Say the word bagpipes and it conjures up the image of a kilted highlander," she recently said. "But it should also bring to mind an old man in Sicily or a soldier in Iraq. Music has been in constant movement and constant change since the time of the ancient world. No culture gets to put the lockdown on anything."

Giddens' restless musical Exploration has won her a MacArthur Genius Award, and this year she was given the Pulitzer Prize in music for "Omar," her opera about enslaved people brought to America from Muslim countries. I had the chance to speak with Rhiannon Giddens just a few weeks before she won the Pulitzer.

We sat down together before a live audience at WBUR's performance venue, CitySpace. And right off the bat I asked Rhiannon Giddens to play us a song, and she kindly obliged.

(MUSIC)

(CHEERS, CLAPS)

CHAKRABARTI: She did that as a favor to me. I was like, "We need to just hear the music right from the start." So thank you so much, so much. Tell us a little bit about what you just played.

RHIANNON GIDDENS: That was a tune called Black Annie that I learned from Joe Thompson, who is a big figure in my life. Who's an 86-year-old African American fiddler that I met when I was in my twenties.

And that's the beginning of the Chocolate Drops. Myself and Dom Flemings and Justin Robinson apprenticed with him. I always say it was my second training. He was the last of a long line of Black fiddlers, that reaches all the way back to the time of slavery. Black string band being a huge unrecognized and almost forgotten tradition that actually forms a lot of the underpinning of a lot of American music.

And so he was our living elder connection to that. We were incredibly lucky because he was the last person really to be playing that kind of music that we know of in the South, so.

CHAKRABARTI: Can I ask you, and you met him, you said in your twenties, right?

GIDDENS: Yeah.

CHAKRABARTI: And that was the first time that you also realized that he was living close by to where you were?

GIDDENS: I mean, I'd never even heard of him. I mean, he was, he was from Mebane, which is like, I went to for my family reunion every year when I was a kid. Had never, didn't know he was there. I mean, I wasn't into, I wasn't playing fiddle and banjo music when I was a kid. I didn't start any of that until I was in my twenties. But, like, on the heels of finding out that the banjo was a Black instrument that was created by people from the African diaspora and the Caribbean, there's that.

And then right on the heels of that was the discovery of Joe Thompson who lived practically in my backyard, you know, and like knew my family's people. And yeah, it was kind of like lucky that we had him, for the time he died when he was 93. We were so blessed to have him. And he was, I think he also felt blessed to have us, you know, people from his community who were interested in this music. But I'm like, "Dang." You know?

CHAKRABARTI: (LAUGHS)

GIDDENS: You kind of go, "Gosh, if it had been like 10 years before that, where would we be?" You know? But it's just like we are so blessed to have the time we had with him, you know?

CHAKRABARTI: Well, so I want to just put a mental pin in that moment. Because you had just said you hadn't been playing fiddle really before that.

So let's go kind of back to the beginning. Because I love the story of, you know, your early years and your musical journey. Where were the biggest musical influences coming from to you when you were a little kid?

GIDDENS: I mean, I would've heard, I spent my early years with my grandparents, my sister and my grandparents, lived out there.

I mean, I saw my mom all the time, but like, I was kind of based out there in the country. And they had jazz and blues records and then they listened to Hee Haw every Saturday night. Roy Clark was my grandma's like, dude, like, and this is my Black side, right?

CHAKRABARTI: (LAUGHS)

GIDDENS: Which should have told you, I mean, like, I literally embody the story that I tell because it's the Black side that watched Hee Haw every Saturday night.

You know what I mean? So it's like, clearly this was coming out of, you know, a shared history, but like, we didn't talk about it. So anyway, so I grew up and then, you know, I was living with my mom and singing with my sister and my dad, you know, my dad was a voice major. But they were hippies and, you know, so it was a lot of folk revival music.

It wasn't a lot of classical or, or you know, it was some pop music, you know, just bunch of this and that. I became obsessed with They Might Be Giants and Tom Lehrer.

CHAKRABARTI: (LAUGHS)

GIDDENS: As you do. Started my weird affinity for like really clever lyrics. And you know, the natural progression from They Might Be Giants to Tom Lehrer was then of course to Steven Sondheim.

CHAKRABARTI: (LAUGHS)

GIDDENS: So, there was no way I was getting out of that one. But I didn't listen to roots music. You know, but I heard bluegrass. My uncle was a bluegrass musician. But I didn't hear any of the stuff that I do. Until I came back from college and went back to North Carolina.

So I approached all of this as an adult. But the groundwork was laid in a weird way, like with the way that I was raised. It's interesting to think about.

CHAKRABARTI: And you sang in a choir when you were --

GIDDENS: I sang in a choir when I was young. Greensboro Youth Course, which taught me how to sit up straight and, you know, breathe from my belly and not from my shoulders.

And how to be in a group, you know, how to sing. I've been singing with my family, like I sang harmony with my sister. We sing together all the time. We still sing together, like almost crawling inside somebody's mouth to like sing the perfect accompaniment to them. And I love doing that. But it started with singing with my sister, you know?

But yeah, I didn't have a lot of formal education in music. You know, I didn't know how to read music. I could pretend, in Greensboro Youth Chorus. Until I went to college, and that's when the full indoctrination into Western art music began.

CHAKRABARTI: (LAUGHS)

CHAKRABARTI: Well, I think in a sense, it sounds like the fact that you weren't thrust into the spotlight at a young age, and had your voice being a source of sort of fame from a young age, allowed you to develop a sense of mental and emotional and spiritual maturity about all that music is and means.

GIDDENS: Yeah, I mean I feel like literally doing the Chocolate Drops, I was five years older than the other guys, you know. So I had already, I had been working a day job, since I got out of school. I worked a day job for five years when I graduated, you know, because like an opera degree and $2.50 gets you a cup of coffee, right?

CHAKRABARTI: (LAUGHS)

GIDDENS: So, I didn't know what to do. And so I was like working, I was working, I had a 401k. I was like doing like marketing and, you know, doing that stuff and wanting to be a musician, a full-time musician. So when it hit and we got to do it, I knew what I was walking away from.

CHAKRABARTI: Yeah.

GIDDENS: You know? And I knew what it was like.

And then I got pregnant, had kids on the road, took them with me, you know, their dad came along and like, it was really hard. But in 200-something days a year, with Papoose on the back and like, you know, trying to do this thing. Talking about Joe Thompson's music and the Black string band, and the banjo being a Black instrument and this mission.

So my first solo record wasn't until I was 37. 37! You know, I did this mission base. I was in sitting in the middle, you know, playing banjo. I got to sing like two songs a set, or something like that, in the Chocolate Drops, you know what I mean? And so I was service oriented. And before that I played Contra dances.

You know, I was a caller. You know, service. That's like that stuff that serves. And I feel so lucky that ... that's what I started with. I just feel lucky. Because I feel for people who are 18 and have a hit that takes 'em around the world. What do you have to say when you're 18? I mean, you have a lot to say, but you know what I mean? It's like you're just starting like, and then you're going to be on record. Saying X, Y, Z. That you're going to look back in 10 years and go, "Man."

CHAKRABARTI: Yeah. Or even look back in like 10 minutes and go, "Eh."

GIDDENS: You know, with the social media. So anyway, I do feel like everything's happened the way it needed to.

Part II

CHAKRABARTI: Now, more from my recent conversation with Pulitzer Prize-winning musician, Rhiannon Giddens. I spoke with her recently at WBUR's performance venue, CitySpace. I've mentioned Giddens' deep study of the diverse connective tissue that forms American roots music.

She's described that as her mission. So I asked her to define more precisely what that mission means.

GIDDENS: I mean, in short, it's really to find the stories of America that exemplify the best of what we are. They're so often covered up. The stuff that we learn in school, I kind of feel like is some of the worst of what we are.

You know what I mean? And we have to learn that, too. But like we don't learn the good stuff that goes along with it, I don't think. And not in the right way. And you find these stories of people. You know, not just African Americans, like so many different groups here in America that like, you know, make it through the most horrific circumstances, the toughest lives, and they make these things of staggering beauty, or they communicate with each other, or they collaborate, and they make this art form or whatever.

These stories of people who just have done these incredible things against all odds. And I'm like, "That's what I want to talk about. That's what I want to hear about." And so I feel like if the impetus wasn't this kind of truth, I don't think I would still be making, like doing this. I wouldn't be sitting here, talking to you.

So again, I'm grateful to have that.

CHAKRABARTI: So give that truth that you're talking about more shape, like what do you mean about this kind of truth?

GIDDENS: Well, like these stories. Like for example, when I started to learn about the banjo, that's what started everything. So I grew up like everybody else. Like, the banjo was invented by white mountaineers in Appalachia.

I mean, that's just what we're told. You know, or that's what we assume. That's like the whole idea and then to find out that it was created in the 1600's by Black people in the Caribbean. I was like, "What?" That's about as far away from mountaineers in Appalachia as you can get. You know what I mean?

So to find that out. But then within that, to find out when you erase that history, you also erase all the cross-cultural collaboration that is also in that history, because that's what it is. You know, eventually everybody's playing the banjo. And that's the beauty of it, you know? So that kind of started me off. Because once I found that out, I was like, "Oh, what else don't I know?"

Right? And so that's kind of driven me. But then as I've been going, the other question has started to come into focus, which is, "In who's best interest is it that I don't know this history?" And I don't think you can ask one without the other. So it's just like the language is so important, and the idea of, "There's always an action that's happening."

People just didn't forget about the banjo in the Black community. You know, there were specific things that were done, happened, erased, whatever. You know, not allowed. All of these things, along with just sort of normal progressions of time. And movement of bodies, and traditions change. But then along with that, there was this concerted effort of erasure. And you know, false narratives, and all of that stuff. Which again, goes back to, "In whose best interest?"

You know, and so what I find is that all of these things are to keep us separated.

CHAKRABARTI: Right.

GIDDENS: Right? All of this, all of the stuff that I feel like I've been digging up. Not alone. I depend on the work of so many researchers and people who are doing this work, you know, primary sources. I just go, "Thank you very much. I'll make a song about this, and on we go." You know?

And so starting to do that with like, slave narratives, narratives by enslaved people, feeling moved to do something with all the emotion that goes along with reading a book like "The Slaves' War." And creating a song from that, which is where "Julie" comes from, which is where "At the Purchaser's Option."

And also focusing on women's stories, because so often it's the women's stories that get left out, and so it's kind of like, and the Black woman is like at the crossroads of, you know, race and gender. So it's just, I'm like, "Well, that's my job. So I'm gonna do my job."

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. So you mentioned, "At the Purchaser's Option."

Wonder if you could play it for us?

GIDDENS: If you want. (CHEERS)

We'll see what's in there. I don't know. I've sung this song a lot. I'm grateful to have it, that it came to me. So I'll do it in that spirit.

(MUSIC)

I've got a babe, but shall I keep him?

'Twill come the day when I'll be weepin'

But how can I love him any less?

This little babe upon my breast

You can take my body

You can take my bones

You can take my blood

But not my soul

You can take my body

You can take my bones

You can take my blood

But not my soul

I've got a body, dark and strong

I was young but not for long

You took me to bed a little girl

Left me in a woman's world

You can take my body

You can take my bones

You can take my blood

But not my soul

You can take my body

You can take my bones

You can take my blood

But not my soul

Day by day, I work the line

Every minute overtime

Fingers nimble, fingers quick

My fingers bleed to make you rich

You can take my body

You can take my bones

You can take my blood

But not my soul

You can take my body

You can take my bones

You can take my blood

But not my soul

You can take my body

You can take my bones

You can take my blood

But not my soul

(MUSIC)

(AUDIENCE CHEERS)

CHAKRABARTI: She tells a story, doesn't she? How do you feel, how does your body feel when you're playing this music, playing that song in particular? Because there's so much power within you that comes out through your voice, through the music. I mean, it's just mesmerizing, just to watch you. I'm wondering what it's like from your experience.

GIDDENS: it's like a divided experience. Yeah. Yeah, I don't know. It's the best I can describe it. It's like there's the me that's kind of going, you know, all the technical stuff. Like, play the right notes, whatever. Like pluck it this, do that, stand here. Open your eyes enough to see if you're still on the mic.

You know, all of that stuff's kind of happening over here. And then there's the rest of it, which is just like, I just can, I guess I could just describe it as conduit, you know? It's just not, I'm just there to ferry. You know, and so it always feels weird to have applause. You know? I don't do those songs for applause.

CHAKRABARTI: Right.

GIDDENS: But for those songs, those are my sacred songs. And I do them because I'm supposed to do them. Because they were given to me to do. So even if I don't want to sing the song, which I didn't, I didn't want to sing that song. But I'm like, that's not up to me. I've been called to sing this song in this particular time, so I'm going to sing the song. And that's when I just let it completely take over.

You know? And it's an honor for that. Because I'm like, "I didn't live through that." It's literally the least I can do to sing about it. You know?

CHAKRABARTI: That's the bridge, one of the bridges that your mission is building.

GIDDENS: When I write a song like that, what I'm doing is I'm creating an emotional shortcut.

CHAKRABARTI: Mm-hmm.

GIDDENS: From the story on the page, or the story 250 years ago, or 400, or whatever, to right now, you know, and that's my job. Like I kind of call myself the performing arts wing of like, you know, the academics. Because I read the books. You know, all the work that they do. They're digging in the stacks and like reading these crumbling, you know, parchments and making these incredibly well-researched books.

And then something inspires me and then I write a song about it. And I talk about the book. You know, "The Slaves' War" by Andrew Ward. That's where I got, you know, that my first one is, or whatever, wherever I get it from. And people may or may not go read that book, but they have a piece of it. Through the song.

CHAKRABARTI: Yeah. I almost feel like it accomplishes two things at once, which almost might seem to be in opposition. Right? Because it's like this beautiful exhibit of music being this uniquely human endeavor, right? That travels and flows and evolves and mixes. But at the same time, you're also drawing on distinct traditions and distinct cultures.

Which brings up the question, and you've thought really deeply about this. Of like, should we consider certain traditions of music as having ownership by certain groups? Or is that the even the right way of thinking about it?

GIDDENS: I mean, I think it always goes back to, in who's best interest do we tell these narratives? And so much behind really nationalistic ways of looking at folk art is the intent to divide and the intent to control. Because the one thing that is constant about tradition is that it changes. It is constantly changing. Now there's a big difference between tradition naturally changing because people move. People have been migrating for millennia. That's what we do.

We move from one place to another, and when we get there, we are changed by the place that we have gotten to and we in turn change the place that we are in, right? So there's this constant push me, pull you flux of how traditions change.

But then I think there's also a way of looking at it where you can respect what that means. And not just pick and choose and like, "Here, I like that. I'm just going to take it and put it on like a coat and then take it off when I feel like it." I think those are two very different things. They get conflated.

People go, "Oh, there is no such thing as cultural appropriation." Eh. Because where we're talking about a power differential, yes, there is. But when you're talking about cultural appreciation, which is just people rubbing up against each other and going, "Ooh, I like that." Musicians, artists, everybody does it.

That's all American music, is constant, you know? But also along with that story is the constant, "Who was profiting from it?"

CHAKRABARTI: Right.

GIDDENS: You know what I mean? I do feel that, you know, but I don't think anybody should feel like they own anything. Like, we shouldn't own any instruments. Like, because instruments travel, they change, people do different things with them.

It could be one person that went from one village in Italy to somewhere, and then all of a sudden everybody's playing that one accordion style.

CHAKRABARTI: Yeah.

GIDDENS: You know what I mean? Or it could be an amalgam of all the different people who came over and it changes into something else. Like all of those stories are true at the same time, you know?

So I think that whenever somebody starts to become a gatekeeper, I am like, "Watch out." And it's like, in whose best interest is it that there are rules? Right? Because if there are rules, then you need people to enforce those rules. Right? And then that means somebody's getting paid, you know? So it's just, and I don't know if, I don't think everybody's always malicious like that, but the system itself is not a healthy one, I don't think.

And we would need to be up here for like five more hours to really get into it. Because it's delicate. I mean, as someone who has been a guest in other people's traditions. I did a lot of work in the Scott's Gaelic tradition. My children speak Irish Gaelic, you know, we live in Ireland. But I've done a lot of research in the Scott's Gaelic tradition, and to me, the language spoke to me.

It was really beautiful, and the story. And then I learned that black people spoke Gaelic in North Carolina, and then I got real interested.

(AUDIENCE LAUGHS)

GIDDENS: And it's that thing about the knowledge of the history can open up all these vistas. So, you know, I went to Scotland, I studied with native speakers of Gaelic. I've listened to loads.

I know what I'm singing when I sing in Gaelic. That's respect. And then when I do my mouth music, I put some scat in there. I do some, you know, I do what I do to it. I'm not trying to sound like you know somebody from Skye. You know, I sound like myself. That's what I tell people when they're like, "Can I sing a spiritual?"

I'm like, "Yes. Should you sing a spiritual like you a 78-year-old Black woman from Alabama? No, don't do that. Sing as spiritual like you are." Because like what are spirituals anyway? They're amalgamation of African and European musical elements that were put together by people who were undergoing a really, really hard thing.

So it's like, why does anybody own that? Nobody owns that. Have respect.

CHAKRABARTI: Yeah.

GIDDENS: Know what you're doing. Take time. Take time. Talk to people who are in that tradition. Find your own personal connection to it so that you can approach it like a respectful guest.

CHAKRABARTI: Mm-hmm.

GIDDENS: You know? And know your own tradition better.

If you know your own tradition and where your own history is, then you can bring something to the conversation. Instead of going, "I have a hole inside, please give me what you have to fill my hole." You know, and we are not encouraged. There is no Blackness, like the idea of the Blackness as a fake construct, right?

Which it is. There's no fake Blackness without an equally fake whiteness. It's all made up. And the target's always moving. So it's like the more that we each know about our own family history, where we come from, where we are based in, what is our family culture, the more that we can then actually have a respectful communication and handshake with a culture that we admire, that we would love to incorporate into what we do.

Part III

CHAKRABARTI: We circled back around to Giddens' own origins. I was particularly eager to know how young she was when she realized that she possesses a uniquely powerful and beautiful singing voice.

It's a question I've asked her in another interview a few years ago. Now, as she did then, she answered with humility.

GIDDENS: You know, like my sister and I were always singing around the house. And one of the things I'm most grateful to my parents for, like I couldn't begin voice lessons until I was 16. Cause my dad was like, "Your voice is still developing, and you shouldn't, you know, just sing. Just sing in a choir. That's what you need to do. Sing in a choir."

So they put me in a choir. And me and my sister were like, "We want to go to do Star Search and we want to sing 'The Greatest Love of All' and like be famous, you know." And like there was just little tiny impulses. We weren't really obsessed with that, but like, you know, the audition comes, you'd like stand in line at the mall, you know?

And my mom was like, "That's nice. If you want to do that, you can do your Kata." So we were in karate. So Kata are the pre, like the movements. There's a series of movements that that help you learn. And when you're a beginner, they're not very interesting. We're not talking like crouching tiger, hidden dragon, like spinning kicks and stuff.

We're talking like, "Thank you very much." Somehow we didn't get picked, and so we would wait in line, and we would do our kata and then we would go home. And so we never like had these moments of, "Hey, we're young people, we got applause for doing this thing." You know what I mean? Okay. For being cute or whatever.

And so I'm really grateful that I held that in with Greensboro Youth Chorus was my real first performing experience with a group of kids singing music together. I could sing, but there was nothing like anointed about my life as a singer. So I wanted to work for Disney. I didn't think about being a professional singer.

I just loved to sing. You know?

CHAKRABARTI: You are so talented, and you've spoken a lot about collaboration. It's a central part of how you approach your mission.

GIDDENS: Yes.

CHAKRABARTI: So, can we talk for just a minute or two about some of your collaborations? With the work that you do with your partner, Francesco Turrisi.

GIDDENS: Mm-hmm.

CHAKRABARTI: You've called him and you doppelgangers.

GIDDENS: (LAUGHS) It was one of those, like how did we meet each other? Like how did that even happen? You know, he's from Turin, he's from the Piedmont of Italy and I'm from the Piedmont of North Carolina.

CHAKRABARTI (LAUGHS)

GIDDENS: And other than that, like none of our music overlaps. Everything that we do is absolutely complimentary.

I went to school for Italian opera. He went to school for American Jazz, but then we're both very, very interested in the folk traditions of our people. And he was interested, you know, I've been obviously championing the true story of where African Americans fit in the creation of the American musical identity.

And he has been talking about how much influence the people who came from the Middle East, and North Africa and the Mediterranean up into Europe, bringing instruments and, you know, numbers and all sorts of things, and how that's been suppressed. You know, in European history, this kind of information and then what does that mean culturally and all of this kind of stuff.

Like, you know, the Couscous festival is in Sicily, right? There's a Couscous festival in Sicily. Like his aunt used to make Couscous. Like this idea of what is cultural collaboration, what is, you know, cultural suppression, what is all of these things? And so we have this kind of parallel tracks that we've been sort of trying to do ourselves.

And so when we met, it was like, kismet.

CHAKRABARTI: Well, we actually have a really good question about that from the audience. Someone wants to know, "Your music and art seems to be a bridge to bring people together in a divided country. Is that a pressure you feel?"

GIDDENS: It's like, an inside-out pressure. It's like, I get tired and burnt out sometimes, but I can't not do it.

You know what I mean? It's like we're all unique and none of us are. You know, it's like we're all put here with a certain set of skills. Would I love to play Dot in "Sunday in the Park with George?" Yes. Are there other people who can do that? Yes. Right? And there's other people who could do my work too, but I'd say there's less.

CHAKRABARTI: Mm-hmm.

GIDDENS: So it's a combination of what is it that I love to do, and what is it that makes me sing, figuratively. But also, what am I supposed to do? Where have I been led? You know, there's this idea of, "What is our responsibility as human beings to the community that we should be serving?" And what we've lost is that connection.

This program aired on June 30, 2023.