Advertisement

How foreign authoritarian rule reaches into the U.S.

Resume

The U.S. government says authoritarian regimes are threatening, coercing and even attempting to kidnap and murder citizens living in the U.S.

The FBI calls it transnational repression.

"It's big and it appears to be getting bigger over the last few years," the FBI's Roman Rozhavsky said.

"We've never seen a concerted campaign by certain governments where they're putting the full force of their intelligence services and all their capabilities on it."

Today, On Point: How foreign authoritarian rule reaches into American society.

Guests

Enes Kanter Freedom, Turkish-American professional basketball player. He played for the NBA with the Boston Celtics, the Utah Jazz, Oklahoma City Thunder, the New York Knicks and the Portland Trail Blazers.

Yana Gorokhovskaia, senior research analyst at the non-profit advocacy group Freedom House. Her work focuses on transnational repression in the U.S. and around the world.

Find a link to Freedom House’s most recent report on transnational repression here.

Roman Rozhavsky, section chief in the FBI’s counterintelligence division.

Find a link to the FBI’s website on transnational repression, including information on how to report your experiences here.

Also Featured

Lucy Usoyan, Kurdish-American protester.

“Leslie," Chinese political activist living in the U.S.

Transcript

Part I

MEGHNA CHAKRABARTI: Enes Kanter Freedom starts our show today. He's a Turkish American professional basketball player who spent more than a decade in the NBA. He was drafted third overall in 2011 and went to the Utah Jazz. From there, his career as center took him to the Oklahoma City Thunder, New York Knicks, Portland Trailblazers, and the Boston Celtics.

So in the United States, Enes Kanter Freedom is a star. But in Turkey, he's a wanted man and considered a terrorist by the Turkish government, which is why the Turkish government has put a half million-dollar bounty on his head. And Enes Kanter Freedom joins us now. Welcome to On Point.

ENES KANTER FREEDOM: Thank you for having me.

CHAKRABARTI: Now we can't disclose the location that you're joining us from.

FREEDOM: Yes.

CHAKRABARTI: Because of the danger that you're under regarding the bounty that's been put on your head. Why does the Turkish government consider you to be such a dangerous person?

FREEDOM: They declared me as a terrorist just because I talk about the human rights violations and political prisoners over there.

I'm a basketball player and I have nothing to do with politics. I have never in my life talked about politics in the United States or anywhere else. Just because of then being a platform, just because of everything I speak becomes a big conversation anywhere else in the world, so they really hate that.

So they're literally trying to do everything they can do silence me. So I was like, you know what? This is a God's gift and I'm going to use it for good.

CHAKRABARTI: What kind of things have you said that you think have drawn the ire of President Erdogan and the Turkish government?

FREEDOM: There are many human rights violations that are happening over there in Turkey right now.

If you look at all the groups like the Kurdish people, Gülen movement, seculars, or many other ones are being persecuted by the Erdogan regime, and also if you're in Turkey, and if you say anything against the Turkish government, you'll be in jail the next day. But if you're outside of Turkey, and if you say anything, they put your name on Interpol list with the red notice.

So any country you go to, if they have an extradition deal with Turkey, then you will be deported back to Turkey and you will become a political prisoner the rest of your life.

And I am so shocked about it.

CHAKRABARTI: You're shocked about it. Okay.

FREEDOM: Because these countries out there, like Turkey, Iran, Russia, and China, they use an Interpol to hunt their opponents. And how can Interpol ... [abide] that.

CHAKRABARTI: Yeah, by the way, I didn't mean to sound surprised at your shock. Because the truth is it probably does come as a shock to many Americans, that just for someone saying what they believe about either our own government or any other international government that can land you on a terrorist list, right?

Because you've been put on Turkey's 2023 most wanted terrorist list. Now there are other, there are some actual terrorists on that list. There's many journalists I know. So like everyone's being lumped together by the Erdogan government.

FREEDOM: I remember I was actually doing a basketball camp in the Vatican, and I met the Pope.

The next day they put my name on that list. Most wanted, terrorist list. I remember having a conversation with the FBI and they said, "Get back to America immediately." Because that is going to trigger a lot of I guess the mafias or serial killers. And the next flight, I took it, came to America and now every place I go, I have to get in touch with the FBI and say, "Hey, I'm going to this city. I'm going to that city. I'm going to out of a country."

So they have to follow my every step. And it is unacceptable. Because I was, I had a hearing in the Senate, and I asked the senators and congressmen, I was like, "Listen, how can a foreign government can put a bounty on a U. S. citizen's head in America?" They had no answer.

This question has been asked to Secretary Blinken and many of the cabinet members, but we had not heard anything from them, because it is unacceptable. They literally put my life in danger in America, and I'm a U.S. citizen.

CHAKRABARTI: So it seems like what you're saying is that the FBI thinks there is a clear danger or threat to your life.

FREEDOM: Of course. Yes.

CHAKRABARTI: Yeah. Has anything happened? Any kind of, I hope not, but any kind of close calls or anything that that you think was came near to actually be threatening your safety?

FREEDOM: Online, yes, of course, I get death threats, daily, from not only everyone's government, but many other dictatorships out there.

And also, I don't know if you guys remember that or not, but when I was playing for Boston Celtics, I went to a mosque and there's actually videos out there. And when I get out of a mosque, the Erdogan supporters verbally attacked me and one of my teammates.

And I wanted to take a picture and video and show that to the whole world. Because sometimes whenever I speak, people think I'm exaggerating, and they think there's nothing going to happen to me in America, I was like, you know what? Let me just take a video and post it so whole world can see it.

So his goons are everywhere in America and any other country. We are lucky to live in America, but many other countries, people are being kidnapped. Just recently, one of my friends just got kidnapped in Tajikistan and they sent him back to Turkey.

Now he's going to become a political prisoner the rest of his life.

CHAKRABARTI: Wow. You said we're lucky to be living in the United States, but the question is that luck running out? Because we wanted to have you, we wanted to invite you to help us start today's show because of growing concern amongst the FBI, and this better than anyone.

They call it transnational repression, that people living in the United States are no longer guaranteed total safety from actions by foreign governments. Now, let me also ask you something else, Enes, if I may. It sounds like you're under, you have to have some additional kinds of security now.

Is that correct?

FREEDOM: Yeah.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. So the threat is definitely real. You've also said that it's not only the Turkish government, which has put you under threat, but you're not currently in the NBA right now. And you say that's because of comments that you've made about China. Tell me more about that.

FREEDOM: So it's actually very crazy because once I started to talk about China, I sit down with some of the government officials, and they literally briefed me about which government can hurt me in what way. Because I don't only talk about Turkey, I talk about the problems are happening in China, Russia, Iran, and many other dictatorships. So I remember sitting down and having a conversation with these government officials. They're like, "Listen, going forward. Here's some of the challenges you are going to face."

The first topic, so they literally briefed me one by one, what government can hurt me, in what way. They said, the first one is China. They said, "Going forward, you will be getting text messages, DMs, tweets or random phone calls from one of the most beautiful girls in the world. Do not answer any of them. They are Chinese spies."

And that messed me up so much. Now, every time I get a message, I don't know if they are really like, that's a message for myself or that they literally are out there to get me. The second one was Russia. They said, "They cannot do it in America, but when you go outside of America, like especially overseas somewhere, when you go to a restaurant, do not go to that restaurant again."

I was like, "Why?" They said, "Because they can trick you, track you, and they can poison you." They said, Iran, "Don't play with woman ... They will come and literally shoot you," which they actually tried to one of my friends." Her name is Masih. She's pretty famous journalist. And the third one, fourth one was North Korea.

They said, "They will try to hack your phone if you ever talk about them." So it's been, I was just shocked to listen to all this, like stories and stuff, but I was like, you know what? The threat is real. And now I don't know if you guys heard about it or not, but after all these like threats and death threats, especially coming from Turkey, I had a conversation with FBI. And when I was playing basketball, they had to come to my place and they set up this thing called panic button, they said, "Whenever you feel uncomfortable, push that button, we'll be there in two, three minutes."

There was a button right next to my bed and one in the living room. They said, "Whenever you feel uncomfortable, push that button. We'll be there." And it's very crazy to me, because I live in the most freest country in the world America, but I had to live with a panic button right next to my back to feel safe.

And we got to do something about it. This is unacceptable.

CHAKRABARTI: Wow. Okay. So just to give people a sense as to the kinds of comments, again, that we take for granted, that we can say in the United States, that have drawn this dangerous attention that you're getting from these various governments. Regarding Erdogan, for example, in Turkey, you've gone so far as to call him the Hitler of the Turkish nation. In China, with your criticism of China, it's actually been very public, right?

I think on your shoes, you've written, No Beijing 2022, Free Tibet, et cetera. Now the NBA, as has publicly said, they've never said that you shouldn't communicate your political or personal feelings, and that they support your right to say these things, but you're still critical of them.

FREEDOM: The reason is the NBA will only care about things until it hits their pocket. When there were all the Black Lives Matter protests were happening, NBA was the first organization, went out there and said, "We encourage every art player to go out there and protest." But when China thing happened, they knew that they were going to lose a lot of sponsorships, TV deals, which they did. Because once I started to talk about the human rights violations in China, the Chinese government took out all the Boston Celtics game of television and that costed NBA millions of dollars.

So look at the numbers, more people watch NBA games in China than American population, and they cancel every Boston Celtics game. It's huge, and forget the NBA. NBPA, the player's association was calling me and say, "Do not wear those shoes ever again." I was like, "Am I breaking rules?"

They said, "No, but you cannot wear them ever again.: So it was, I was very shocked. Because NBA, I thought NBA was standing with justice, with freedom. Democracy. It's all a lie. Trust me, until it hits their pocket, they're going to advocate whatever they believe in, but when it hits their pocket, they're going to be silenced.

And they will silence anyone who goes against their agenda.

CHAKRABARTI: Enes Kanter Freedom, a celebrated center for the NBA until last year. Enes, thank you so much for joining us.

FREEDOM: Of course. Thank you for having me.

CHAKRABARTI: Enes helped us kick off the story today because we are talking exactly about the growth in the kinds of things that he personally has been experiencing.

The FBI calls it transnational repression or foreign governments threatening the security, safety and even lives of people living in the United States.

Part II

CHAKRABARTI: Yana Gorokhovskaia is senior research analyst at the nonprofit advocacy group Freedom House, and her work focuses on transnational repression in the U.S. and around the world. So Yana, welcome, and first and foremost, how would you define what transnational repression is?

YANA GOROKHOVSKAIA: Sure. Thanks for having me. Transnational repression is a term that we use to describe an array of tactics used by governments to reach across borders in order to silence dissent. And that could be among activists, dissidents, journalists, and students and others.

CHAKRABARTI: Now, I have to be honest, our producer, Stef Kotsonis, who put this hour together has been talking about this for a while and it didn't really register on my list of pressing issues.

Until just this month, there was this news story that the U.S. thwarted a plot recently to kill a Sikh separatist who was, who's living on U.S. soil. The plot was by the Indian government. Can you tell us more about that, Yana?

GOROKHOVSKAIA: Yeah. So the Indian government, so the big news was a few months ago when the Canadian government actually, Justin Trudeau announced in parliament that they suspected the Indian government of having assassinated a Sikh leader in British Columbia in the summer, and that sparked off a series of stories and sort of news reporting about threats against the Sikh community here in the United States, including this latest report.

And India is an interesting case because I think as your previous conversation demonstrated, when we think about transnational repression, we often think about authoritarian governments, not democratic partners of the United States, but in fact a whole range of governments engages in transnational repression.

Freedom House has identified actually 38 governments who have undertaken acts of transnational repression across 91 countries since 2014.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. And those acts go so far as from what on the mild case to what on the severe cases?

GOROKHOVSKAIA: The transnational repression includes everything from coercion of family members, threats, harassment, both in person and online.

And then everything like assassination attempts, assaults, detentions, renditions. Unlawful deportations. We at Freedom House only track the direct physical incidents, so these are not things that happen online or threats against family, partly because those are very hard to verify. And so we feel comfortable in saying that there's been at least 854 incidents since 2014 of just the direct physical acts of transnational repression that we can verify.

Okay, and those are things that are, those are 800 plus acts around the world?

GOROKHOVSKAIA: Around the world. Yes. It's much more common in sort of authoritarian neighborhoods, so if you think about Southeast Asia or the Middle East, where countries that are like minded in terms of their disregard for the rule of law and human rights can cooperate together to target people.

But these things also happen in the U.S., in Canada, in Europe in democracies where people, I think, tend to feel more secure.

CHAKRABARTI: Are those things happening more? In, say, North America, Canada, and the United States, because it seems like when something like a successful assassination in Canada and a thwarted attempted one by the Indian government, presumably, in the United States, that doesn't show up in the news very often.

So are countries feeling more emboldened to try to physically harm dissidents or activists in the United States?

GOROKHOVSKAIA: I think to a certain degree that's true, in part because there's a lack of accountability for transnational repression. So if you think back to the heinous murder of Jamal Khashoggi, who was killed in Istanbul, the Saudi government, at first, there was a big backlash and reaction to that.

But in general, the Saudi government has not really paid a price for that. If you think about the targeting, Enes mentioned Masih Alinejad, who lives here in New York. She has been the subject of at least two plots. One, a kidnapping plot and one, it seems a thwarted assassination plot in the last two years by the Iranian government.

And the Iranian government is already under a lot of sanctions, but there hasn't been a specific reaction in terms of the transnational repression kind of aspect of it. And so I think awareness is going up, you have the FBI paying a lot of attention to this issue, but there's the other side of it, which is the accountability for the foreign government that's undertaking this.

CHAKRABARTI: So this is where it becomes very murky and complex, right? Because in the case of the thwarted assassination plot here in the United States, U.S. authorities were in touch with the Indian government, saying that, "We know something's going on." The Indian government says activities of that nature aren't part of their policy.

Activities being threatening the lives of people living in the United States. But I think the complexity comes with how, in this example, the Indian government, sees the Sikh activist in the United States. I'm seeing a foreign ministry statement that says, yes, the U. S. raised information to the Indian government, but that information had to do with a quote, "Nexus between organized criminals, gunrunners, terrorists, and others." And the statement went on to say, that information, "It was a cause for concern for both countries.

And India takes it seriously."

Is this an issue of foreign governments seeing activists as a greater threat than the United States would see those same people?

GOROKHOVSKAIA: I think this is foreign governments learning to speak the language of anti terrorism and extremism. A lot of people who are targeted in this way are targeted, are labeled first terrorists, or extremists or members of a terrorist organization.

And that taps into this very securitized international network of cooperation between governments, whether that's Interpol, whether that's other forms of legal cooperation. It is a tool when governments label someone a terrorist or an extremist. They know what they're doing, essentially there, and the acts for which these people are labeled as terrorists or extremists are often things that we think of as just normal free speech.

Normal activism, journalists reporting on things or average people talking about human rights violations in a different country. That's why they're being labeled extremist and terrorists.

CHAKRABARTI: So it must be asked then Yana, has the United States participated in the same kind of transnational repression?

GOROKHOVSKAIA: I want to be clear that the United States, as far as as we know, has not perpetrated transnational repression, which is the targeting of your own citizens abroad with force or with threats, but I do think it's fair to say that the uptick in the rhetoric about terrorism and increased international cooperation has made some of these acts of transnational repression easier or just more possible.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, but weren't there, hasn't the United States definitely assassinated U.S. citizens abroad as saying that they were targets of, as you mentioned earlier, the war on terror?

GOROKHOVSKAIA: Yes, but those have been in areas of conflict or active war.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, so that's considered different, even though that citizen never got a chance to make their case in a court?

GOROKHOVSKAIA: Yeah. So again, I want to be clear that violations of the rule of law and not following normal procedure to actually put someone before a court, and, you know, play out their entire case, that's problematic. But targeting someone because of their speech is very different from those scenarios.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, understood, but I guess what I'm trying to needle in here is that, gets back to what you were saying, is that governments are using the same kinds of language to justify their actions on people living here on U.S. soil.

GOROKHOVSKAIA: But the United States and other democracies, as far as I'm aware, or the sort of more established democracies, are not trying to silence their dissidents living abroad.

I think you can bad mouth the United States wherever you live without kind of fearing reprisals. So it is different in that sense. But I do think that the security structure that was established with the war on terror is one that we have to now think about. How that facilitates the acts of autocrats when they're trying to track down dissidents and activists abroad.

CHAKRABARTI: No, I appreciate you engaging in this particular exploration with me, Yana, because this is, this may be one of those things where U.S. exceptionalism applies in a good way. We're not actually targeting hopefully people living abroad who speak their mind about the U.S. But, I want you to stand by here, Yana, if you can, for a moment. Because let's quickly hear a story from someone who's experiencing transnational repression from the Chinese government. Her name is not actually Leslie, but that's what we're going to be calling her because she is deeply concerned about her security.

She's a Chinese national living and working in the United States and she's part of a loosely organized group of political activists who have held protests in U.S. cities against the Chinese government. Now she's so concerned about her safety that we have masked her voice and her words are being read by another person.

LESLIE: They found out some evidence showing that I spoke against Chinese government's zero COVID policy and human rights violations. They came to my parents and said, "We think your child is jeopardizing national security." So they keep interrogating me through my parents, saying, "Did you post this? Did you say this? Did you do that? Do you own that Twitter account?" Everyone in my family is worried and scared.

CHAKRABARTI: So Leslie there talking about how the Chinese government isn't just targeting her, but her family in China, as well. She also told us she's surprised at how Chinese authorities can infiltrate American social media apps to spy on its citizens in the U.S.

LESLIE: I was surprised at how deep they can penetrate social media here to find us. I'm not so surprised that they want to do that. Because within China, they monitor almost literally everyone's laptop and cell phones to figure out what we are talking about. I'm surprised, but also not so surprised.

CHAKRABARTI: And Leslie finally told us that she is so concerned about her safety, and her fellow activists are as well.

They don't even use their real names with each other.

LESLIE: I think everyone is afraid of the Chinese government's transnational repression. It's common sense that if you say something against the Communist Party, that you never use your real name and you never show your face on the internet. Unless all your family either has already cut ties with you, or they're not living in China.

As long as you have something you really care about living inside China, then don't expose yourself.

CHAKRABARTI: That's U.S. based Chinese political activist, Leslie, again, not her real name. Joining us now is Roman Rozhavsky, section chief in the FBI's counterintelligence division. ... Roman, welcome to On Point.

ROMAN ROZHAVSKY: Hi, Meghna. Thank you so much for having me. So let me ask you, let's say about a decade ago, or a decade and a half ago, how much was the FBI working on transnational repression?

ROZHAVSKY: Not, definitely not as much as right now. We did have individual cases, but we never connected them together, that they were part of these campaigns by foreign governments and their intelligence services.

CHAKRABARTI: So then what changed? It sounds like something or the awareness grew substantially around 2020.

ROZHAVSKY: We started seeing that these were concerted campaigns and that people were being repeatedly targeted for speaking out on U.S. soil. And the tactics were similar. In them being targeted, for example, as we heard from the victims you've had on the show, on social media, online threats, their families being threatened.

One other tactic that we've repeatedly seen was hiring private investigators to surveil.

CHAKRABARTI: Can you tell me, I don't know if you can mention specifics about any particular cases that you've worked on, but it'd be helpful to get a deeper understanding of just how consuming trying to live with this kind of repression can be for the people who are experiencing it.

ROZHAVSKY: I can talk about some examples from cases that we have publicly charged. There is the example of the dissident in New York that was targeted by the Iranian government. And in that investigation, they hired a private investigator, told the private investigator that they were looking to recover a debt, and the private investigator surveilled the dissident who actually noticed the surveillance and came to us.

We had counter surveillance. We ran into the private investigator. We talked to him and he helped us identify the plotters who were led by an intelligence officer from Iran. So that case we publicly charged. And it's important for us to, even though the intelligence officer is in Iran. But it allowed us to tell the story, that it was the government that was perpetrating this.

And we're going after this dissident just for speaking their mind.

CHAKRABARTI: And that's not the only one, obviously, that has been publicly charged. There have been other indictments as well, Roman?

ROZHAVSKY: We've had several. For example, last year, we announced three different indictments, in 2022, against officials from the PRC government who were, in one of those cases, they tried to interfere in the campaign of a former Tiananmen Square protester who was running for Congress in New York.

They hired a private investigator there, as well. And tried to obtain derogatory information so they could derail this person's campaign. Because they didn't like his politics. In that case, the private investigator also worked with us and we were able to warn the victim and and prevent the disruption of their campaign.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, because that leads me to a question that we're receiving via social media from one of our listeners who says, "I'm not sure what people who are experiencing this think the U.S. government can do about what these foreign governments are doing." Roman, what's your response to that?

ROZHAVSKY: I would say we have arrested the people that were involved on U.S. soil.

For example, the third case that I just mentioned involved the PRC government hiring a witting private investigator who burned down a dissident statue. This dissident had built a statue to protest the PRC's COVID policies and the private investigator burned it down. And he was arrested and he is actually pleaded guilty and will be sentenced.

The U.S. government can, we will do everything in our power to protect the victims from, physical threats. And then we will go after the foreign government officials who are orchestrating the activity, to tell the story.

CHAKRABARTI: Now, and Roman, very briefly, just yes or no, and then we'll carry it over into the next segment.

But in this case that you're talking about, was a federal law enforcement officer part of this kind of plot against the dissident?

ROZHAVSKY: Yes, that's right. There was also a federal law enforcement officer that was charged and arrested.

Part III

CHAKRABARTI: I just have another couple of quick questions for Roman about the case that you were talking about, Roman, before the break, the involvement of the federal law enforcement officer, along with that private investigator, both of them were charged in violations of U.S. law in assisting the Chinese government in harassing the dissident here in the United States.

What was the motivation of the law enforcement officer, Roman?

ROZHAVSKY: So to give a little context, so the victim in this particular case was also a former Tiananmen Square protester, but this person wasn't vocal in any way. And they have a daughter who was set to compete in the Beijing Olympics in 2022, and the PRC government really wanted to know if that person would travel with his daughter, presumably so they could arrest him.

So they hired a private investigator to try to find out whether this person was traveling. They posed as an Olympic committee official to try to interview the victim. And we had warned the victim because we knew this was happening. So then a different private investigator they hired reached out to the federal law enforcement officer and asked them to help by checking a database that would show whether the person was traveling or not.

This is just an example of how far reaching transnational repression is and how many, how much resources these governments are putting into it. Because it's such a priority for them.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, this question is still lingering in my mind about why we're seeing a growth of these actions here in the United States, and I presume neither of you argue against that we're seeing a growth in it. Because does it indicate some sort of just growth in confidence by these foreign governments, or is it a weakening of the ability of the United States to protect these folks.

What do you think it is, Roman?

ROZHAVSKY: All of those reasons are probably a part of it. I think the biggest part though is as you said earlier in the show. To Americans, it's not a big deal to criticize the government. It happens all the time. But in these other countries, it is a big deal.

If you criticize the government, you will be imprisoned and they view it as a massive threat to their stability and they want to stay in power. That's their number one goal. And so to them, a dissident who has millions of followers on social media is a huge threat. And so they're willing to take bigger risks and to silencing them.

CHAKRABARTI: Huh. And the fact is, it sounds like for many of these countries, for example, the ones that Yana has been tracking, given that they're nations like China, they have the resources to undertake these kinds of actions. So it's a marriage of authoritarianism and growth of national resources.

I want to come back to, in a minute, the question of what can be done, what can be done to protect people who are living here in the United States from these kinds of actions by foreign governments. And in order to do that, we have one more story here of someone who has been able to take some action.

She's Lucy Usoyan, Kurdish American, and Lucy lives outside of Washington, D C.

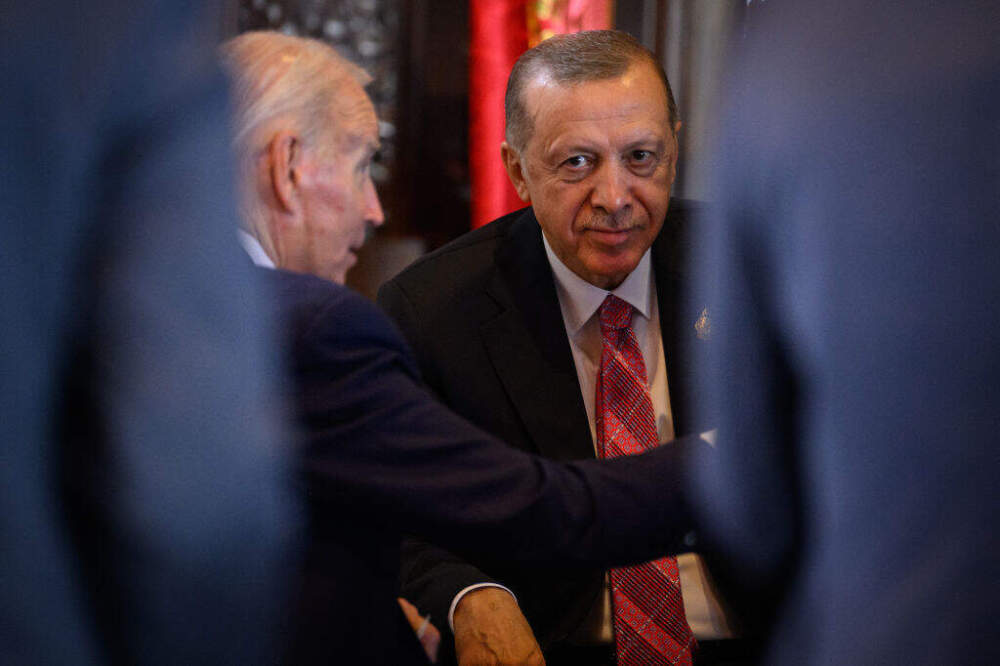

Self employed, developing a line of cosmetic stores. And she's also around, she's one of about 20 people who is suing the Turkish government in a U.S. court after an incident involving Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

LUCY USOYAN: It was on May 16th, 2017, Erdogan was coming to visit White House.

He was welcome to White House and we didn't feel like he was welcome. So we went to join the peaceful protest there to express our own opinion and oppose it.

CHAKRABARTI: And not only does Lucy say the protest was peaceful, but she says it was an act of freedom of speech guaranteed by the U. S. Constitution.

USOYAN: The protest ended very nicely, and then we, everyone was walking in the direction to catch their ride back, to have a lunch and then leave. And then as we were walking, we passed the Sheridan circle and then we saw an opposing group. It was a support of Erdogan. It was his supporters. They were there, and there was a shout and verbal exchange and then very quickly it switched to the physical brawl.

CHAKRABARTI: And as Turkish President Erdogan looked on, his security detail rushed the dispersing protesters and physically assaulted them. There's some indication that it may have been Erdogan himself who ordered his staff to attack Lucy and the others.

USOYAN: There was a video showing how he walks out of the car, he looks at us, and then he speaks to his security team. And, like, moments later, we see that the group just rushes through us. He secured the team, actually.

CHAKRABARTI: Lucy was caught off guard.

USOYAN: I just didn't grasp the moment. And I didn't have a chance to run away.

I was just knocked out and knocked off on the ground. And then I remember I was getting kicked in the head predominantly. And then I blacked out. And when I opened my eyes, I saw that people were bloodied. And I found myself on the ground.

CHAKRABARTI: Erdogan's security officials also attacked American security agents.

The Turkish security officials then rushed to a waiting airplane at Joint Base Andrews and fled the country before they could be arrested. One U.S. agent described it as the fastest, quote, "joint move and departure I've ever seen in my 16 years on the job," end quote. Lucy and others filed suit against the Turkish government, but the Turkish government that they had, they and their security team enjoyed a diplomatic immunity.

And they made that argument all the way to the U. S. Supreme Court, but they lost there, which has allowed Lucy Usoyan and other protesters to take further action.

USOYAN: Myself and the rest of the plaintiffs, all of us, which were present and we got physically attacked by the security guards of President Erdogan, we are suing the Turkish government in American courts.

CHAKRABARTI: So that was Kurdish American citizen Lucy Usoyan. She spoke with us from Alexandria, Virginia. So Yana, are there other cases that have been able to buy people who were the victims that they've been able to successfully bring to a U. S. court that you know of?

GOROKHOVSKAIA: There's been other attempts, including trying to sue the government of Saudi Arabia in court.

There are obstacles though, like the Foreign Sovereign Immunity Act, which prevents people from suing a foreign government. But I do want to say that I think it shouldn't be the onus of victims to take up. I think it's great that people feel empowered to use American courts to try and seek some justice, but it's really on the government of the United States to protect people who live inside its borders.

And for that, we need an act of Congress, essentially, we need policies. Right now, there's the Transnational Repression Policy Act, which has been tabled in Congress by Merkley, Haggerty, Rubio, and Cardin. And that act would set out a policy and coordinate action on transnational repression across government agencies.

And that's really important. Because right now we don't have that, despite the excellent work that the FBI and other agencies, including DHS, have done on this topic. We don't have a policy agenda. We don't have a definition that's codified of transnational repression. So we're lacking these really fundamental tools.

CHAKRABARTI: I see. Is that one of the things that makes even existent prosecutions so challenging, Yana, because there isn't a clear legal framework around what exactly these governments have done? That's that's breaking U.S. law.

GOROKHOVSKAIA: Yeah, that's definitely part of it. I think as Roman was saying, you can arrest people, you can charge people, because things like stalking or assault or threats are still crimes under U.S. law. But there's this added element of working on behalf of a foreign government. And that's captured somewhat under FARA, but FARA is a really outdated regulation or law, and it wasn't intended for this.

And it's really a transparency mechanism. It's not an accountability mechanism. And so there are gaps in U.S. law right now that make really going after this difficult.

CHAKRABARTI: I see. Roman, let me turn back to you. Because earlier in the hour, we heard Enes Kanter Freedom talk about the amount of protection he's getting from the FBI. And the amount of cooperation that the FBI is giving him in regards to keeping him safe, keeping him alert, et cetera.

But I imagine that this must be a little challenging for the FBI, because folks who are on the receiving end of the transnational repression know that it's happening because of a foreign government. Perhaps they might be reluctant to turn to another government, the U.S. government, for assistance.

ROZHAVSKY: Yes, that is absolutely accurate. I have done victim interviews where they, the victims have said that very thing. Where there's a lot of propaganda coming from, for example, the PRC government that says the FBI will work with us. And if you dare to say anything about us, or if you go complain to them, they'll just turn you over to the PRC.

A large part of the reason I'm here is to get the word out and to tell the public that this is a priority for the FBI and that we will do everything in our power to protect the victims. Another thing that I want to say is one of the biggest problems is that a lot of people just haven't heard of transnational repression, so they don't realize that it's illegal and they don't realize it's a problem.

And so sometimes when these cases are reported to, let's say, local law enforcement at first blush, they sound like a civil dispute, right? Like you got into an argument with someone online about your political views or even worse. Sometimes they sound like the person is paranoid, when they say, "I'm being followed."

So it's really important for us at the FBI to get the word out and to provide the context that these are foreign governments doing this. And once you have that context, whether you're local law enforcement or a private investigator, when you see that the person targeted is a vocal dissident, it all makes sense.

CHAKRABARTI: I see. Speaking of foreign governments, Yana, three names in particular have come up frequently in this hour. We talked about India, Turkey several times, and of course you mentioned Saudi Arabia as well. A complexity there is that those three nations are ostensibly U.S. allies. Does that make it more challenging to, or limit, say, the FBI's power, the Department of Justice's power, or willingness to really pursue the governments that are engaging in this kind of repression?

GOROKHOVSKAIA: I haven't seen any lack of action by the FBI. I think the FBI and other agencies domestically are doing a really great job on this. I think the point around people reporting is certainly a valid one. And there's lots of countries, I think the big ones we're talking about China, Saudi Arabia, Russia, Turkey, Iran, those are big players, but 38 governments around the world engage in transnational repression.

These are places like Cambodia, Rwanda, they're going after dissidents. The Central Asian countries, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, they're pursuing dissidents abroad. And I think it's hard to convey to people that this is a serious problem, that all of these governments are going after dissidents.

And again, there is still a lack of accountability internationally on this issue, not only just from the United States, but from other countries as well. This is a problem in the UK, this is a problem in France, it's certainly a problem in Germany where a dissident was attacked with a hammer by someone that was sent by a foreign government.

So this is a worldwide problem, and it will require coordinated action between democracies. We've seen a little bit of that, with the second summit for democracy. We saw that a little bit at the G7, but much more action is needed.

CHAKRABARTI: Points well taken that this is happening in a lot of different places.

The UK, right? We have several examples of poisonings and assassinations by Russia on UK soil. So that much is clear. But you heard Enes earlier say that he alleges that the NBA is unwilling to use whatever massive financial resources that it has, and I presume it's got pretty good connections in the U.S. government, to do anything to protect him from, sort of Chinese actions, based on his criticisms of China.

Because China's such a huge market for the NBA. That has to lead to some delicacy around the extent to which the U.S. can use diplomatic levers to protect folks, right?

GOROKHOVSKAIA: Sure, but I think we have to be a little bit more imaginative.

There are a lot of different things that the United States can do. So one of the things that the U.S. can do is condition foreign security aid around this issue. So we, in some cases, are providing weapons and security cooperation to governments that perpetrate transnational repression. These are cases like Saudi Arabia and Egypt and Rwanda.

We don't have to be providing that security aid, we don't have to be selling weapons, right? You can maintain, no one is saying, you have to break off all diplomatic contact or you have to have all of these really severe measures. But there are a lot of tools in our toolkit, in our diplomatic toolkit that we can be using, that we aren't using right now.

And going back to this issue for victims, it sends a message, right? If you are being targeted by the Saudis in the United States, and then you see the President of the United States visit Riyadh, that sends a message to you about how seriously your complaint, if you were to go to law enforcement about this, how seriously that would be taken.

So I think that's another kind of issue we should be aware of.

CHAKRABARTI: We just have a few seconds, Roman. I want to give you the last word today. What do you want people to know about the growth of transnational repression in the U.S.?

ROZHAVSKY: I would just say transnational repression is an attack on democracy.

It's an attack on freedom of speech and anyone who cares about preserving our democracy should care about stopping transnational repression. And I would just like to say the FBI will do everything it can to protect victims. So we encourage everyone to come forward. You have our website. There's also 1-800-CALL-FBI where we have specially trained the call takers. So we're here if you need us.

This program aired on November 29, 2023.