Advertisement

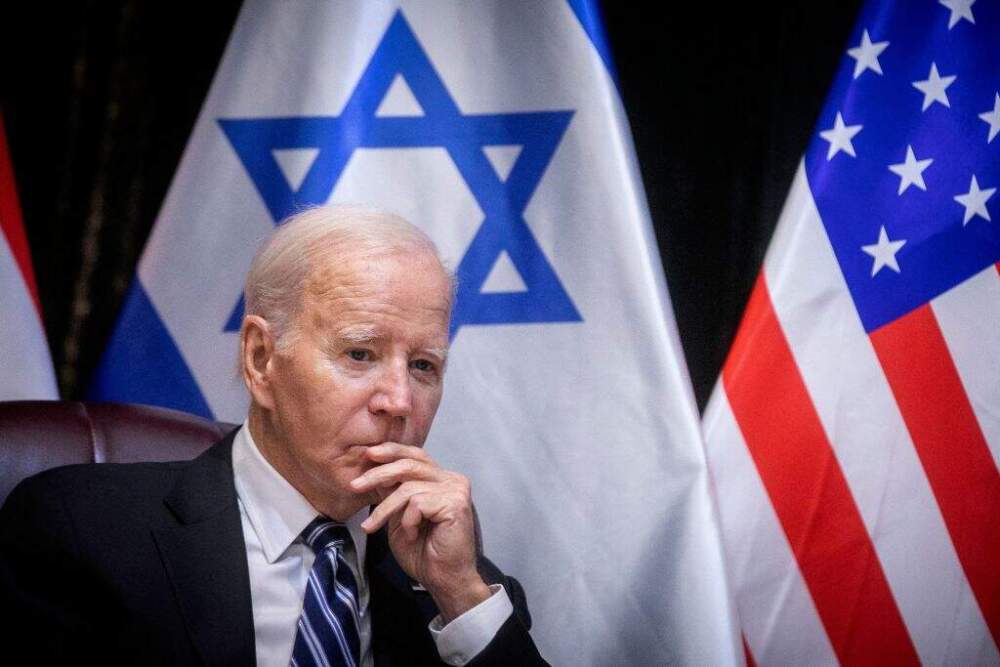

The Biden approach to Israel

Resume

President Biden has fully supported Israel since the war began.

"During the crisis, he became the father figure for most Israelis, the kind of father figure that we don't have domestically," Nimrod Novak says.

Biden has been consistent on his tight embrace of Israel.

When he was vice president, he advised President Obama that's best way to get concessions out of Israel. Obama disagreed.

Is the Biden method paying off today?

"Although the jury is still out midway through the crisis, it seems that President Biden has been wiser than President Obama in handling the Israeli arena," Novick adds.

But lately, many American voters are loudly criticizing Biden. And those who know him think it may be time for a course correction.

"I would give him an A plus in managing the relationship with Israel," David Hale says. "I would question whether the level of messaging on the conduct of the war is really going to leave us where we want to be."

Today, On Point: The Biden approach to Israel.

Guests

Nimrod Novick, former senior policy advisor to Prime Minister Shimon Peres. Israel fellow at The Israel Policy Forum (IPF), an American Jewish bipartisan organization.

Amb. David Hale, former undersecretary of state, special envoy for Middle East Peace, deputy assistant secretary of state. Former ambassador to Jordan and Lebanon. Fellow at the Wilson Center. Author of the forthcoming “American Diplomacy Toward Lebanon."

Transcript

Part I

MEGHNA CHAKRABARTI: Days after Hamas fighters invaded Israel on October 7th, and as Israelis were still in shock, grieving over the carnage and cruelty, President Joe Biden flew to Tel Aviv with a simple message.

The United States, as always, is on Israel's side.

PRES. JOE BIDEN: For decades, we've ensured Israel's qualitative military edge. And later this week, I'm going to ask the United States Congress for unprecedented support package for Israel's defense. We're going to keep Iron Dome fully supplied so we can continue standing sentinel over Israeli skies, saving Israeli lives. We've moved U.S. military assets to the region, including positioning the USS Ford carrier strike group in the eastern Mediterranean with USS Eisenhower on the way.

CHAKRABARTI: He also issued this warning to Israel's neighbors.

BIDEN: My message to any state or any other hostile actor, thinking about attacking Israel remains the same as it was a week ago. Don't. Don't. Don't.

CHAKRABARTI: This has always been the Joe Biden way through his decades in the Senate and now as President of the United States.

He always has said the best way to influence Israel is to keep Israel as a steadfast, close ally, able to rely on U.S. support. At least publicly. But lately there's been a change in tone from his administration, hints of frustration that the Biden bear hug isn't working. In the last few days, secretary of state Anthony Blinken, secretary of defense Lloyd Austin, and vice president Kamala Harris, have all cautioned Israel publicly.

Here's Harris.

KAMALA HARRIS: As Israel defends itself, it matters how. The United States is unequivocal. International humanitarian law must be respected. Too many innocent Palestinians have been killed. Frankly, the scale of civilian suffering and the images and videos coming from Gaza are devastating.

CHAKRABARTI: So today, we'll scrutinize President Biden's years of ironclad public support for Israel, and how he's deployed that support during the Israel Hamas war.

We'll also ask whether it's been effective at helping Israel itself and whether it's time now that Biden rethink his approach. So joining us today is Nimrod Novick. He's in Tel Aviv. He's a former senior policy advisor to Prime Minister Shimon Peres and is the Israel Fellow of the American Jewish Bipartisan Organization, the Israel Policy Forum.

Mr. Novick, welcome to On Point.

NIMROD NOVICK: Thank you, Meghna, for having me.

CHAKRABARTI: Also with us today is David Hale. He's with us from Washington. He's former Undersecretary of State, Special Envoy for Middle East Peace, Deputy Assistant Secretary of State, and former Ambassador to Jordan and Lebanon. He's currently a fellow at the Wilson Center, and author of the forthcoming book “American Diplomacy Toward Lebanon."

Ambassador Hale, welcome to you.

DAVID HALE: Thank you very much, Meghna, and please call me David.

CHAKRABARTI: I shall do that. Thank you for the permission. Let me ask you both first. And Nimrod Novick, let me start with you. Let's just reflect for a moment on those clips that we heard during President Biden's visit to Israel in just the first days after the terrible attack on October 7th.

What did you think of his specific language that he used that day when speaking to not just Prime Minister Netanyahu, but the press in the world at large?

NOVICK: I looked at it naturally from an Israeli parochial perspective, and there was no doubt that the chord that he hit struck deeply in Israeli hearts.

He gave Israelis the father figure that they don't have, that we don't have domestically. He embraced us. It was the ultimate expression of his long self-identification as a non-Jewish Zionist.

CHAKRABARTI: And that was a familiar tone to Israeli ears coming from Biden from many years, would you say that?

NOVICK: Absolutely. Only this time it was reinforced with very powerful action. As you mentioned, the dispatch of the area, the carrier task forces, the nuclear submarine, the warning to third parties, the support package in Congress, the airlift, munitions that Israel is using today, arrived from the U.S. two, three, four days ago.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. Familiar and steadfast language, but also followed by almost immediate action. Point well taken, Mr. Novick. And Ambassador Hale, I promise I will call you David eventually. But Ambassador Hale, same question to you. Because political language is always exquisitely important, but perhaps no more so than after devastating event like this, there was a lot on the line regarding what the president said on that trip to Israel.

How would you also analyze the particular language that he used in expressing his support for Israel?

HALE: I thought it was absolutely essential that he do what he did, and I think it's very much characteristic of, as you described, his philosophy toward the relationship. Although I would say that I think almost I can't conceive of an American president, after the wake of what happened on October 7, not saying, taking a similar approach of absolutely stalwart support for Israel at a time of enormous emotional and security stress.

Glad it was done, and I think, as Nimrod pointed out, actions also are very important. And one of the things that the administration focused on, really from day one, was our role in messaging in the region against escalation. And again, if the president had not taken a strong rhetorical stand, he did take, and if he had not committed the military actions that we took, you would have had a crisis in the relationship with Israel. And you would have had Israel wondering who had its back and what was going to happen in the region, and then you had the risk of an escalatory cycle.

Now, Iran and its proxies were doing precisely that and have continued to escalate, but it could have been much worse if we had not conducted that early messaging through all channels and through actions.

CHAKRABARTI: Yeah. So this is a really important point David, and I'm glad you brought it up, and that is, this was in the immediate aftermath of that terrible day on October 7th, so nothing short of very strong, supportive language would have been likely to come from any president of the United States.

But the other thing that interests me is at that time, that time being like just two months ago, in fact, two months ago to the day, the entire administration definitely fell in line behind President Biden and his approach to taking a close embrace of Israel. The fact is that seems to have changed in the subsequent two months.

And we're going to talk about that a little bit later in the show. But Nimrod Novick, I do want to spend a few minutes going back in time and discussing a little bit about where Biden's seemingly unwavering support for Israel that he has publicly declared over the past many decades, where some of its origins might be.

And I understand that one of them, and in fact this is because Biden himself has talked about it quite a great deal, comes from a 1973 meeting that then Senator Biden, I think he was just in his 30s, a meeting that he had with former, now late, Prime Minister Golda Meir. Do you know about what happened at that meeting, Nimrod, and why it's so important to Biden himself?

NOVICK: It's almost impossible not to know, when President Biden likes to repeat the story on every occasion, including during his various meetings in Israel when he was here recently. And yes, the story is told, or the way he recalls it, is that after the '73 war, he asked Prime Minister Meir, what's the source of strength of this small country in such a hostile huge neighborhood?

And reportedly, Golda Meir responded, "The source of our strength is a single fact. We have nowhere else to go."

CHAKRABARTI: That seemed to have had a powerful impact on young Senator Biden. Which is not, it doesn't seem to have changed at all, regardless of the various conflicts and the evolution or the change in the state and government of Israel and the subsequent many decades, Nimrod?

NOVICK: Yeah, he, I don't want to say claims, because I trust that's the story. He says that his commitment to Israel was born at his father's, at his parents' home. The education, the way he was brought up was to believe in the right of the Jewish people for self-determination and that the main superpower of democracy and freedom should support it. But yes, his relationship with Israel as a senator, his record is impeccable in terms of voting record of everything that is supportive of Israel.

As vice president, he even surprised some of us. Because there was an incident when he landed here as vice president and was welcomed by the then, still, Netanyahu, announcing the government announcing major settlement construction at the time that this was an anathema to the Obama-Biden administration.

He was furious. He went back home, flew back and in the deliberation, from what we heard from the deliberation in the White House, he was the one who suggested the soft approach, whereas the president and others thought that Netanyahu should be taught a lesson. That's not how you welcome the vice president of the United States.

So we're going to talk more about that division or the rift between then Vice President Biden and then President Obama. But David Hale, we've just got about 30 seconds before we have to take our first break. Do you see that same resonance that Nimrod was talking about from Biden's early, that early meeting in his career with Golda Meir?

HALE: Oh, sure. I think that it shows the value of travel by senators and congressmen. Because they are often in office for a very long time, and they build these relationships that are very personal. But It's not all about personality. I think we also have to bear in mind, we have very important interest at stake in this relationship and the president knows that well.

Part II

CHAKRABARTI: Gentlemen, for the bulk of this segment, I do want to go back a little bit in time and talk about what Nimrod, you had mentioned, the differences in opinion and approach between then Vice President Joe Biden and President Barack Obama.

So let's start with a clip from May of 2011, and this is when Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who was Prime Minister of Israel at that time, followed with a break thereafter, and of course now is Prime Minister once again, when he visited the White House. And he basically, during a press conference, gave something of a lecture to President Obama for seven long minutes in the Oval Office. And the news cameras were rolling, and Prime Minister Netanyahu seemed to be schooling President Obama on the basics of the Middle East conflict.

And if you look at the TV footage of this moment, you can pretty clearly see that President Obama, even though he tried to always act in a no drama way, his face was communicating anger. So here's a little bit of their exchange, and it starts with Netanyahu followed by Obama.

NETANYAHU: I can only express what I said to you just now, that I hope he makes the choice, the right choice, of choosing peace with Israel.

BARACK OBAMA: Our ultimate goal has to be a secure Israeli state. A Jewish state living side by side in peace and security with a contiguous, functioning and effective Palestinian state. Obviously, there are some differences between us in the precise formulations and language. And that's going to happen between friends.

CHAKRABARTI: Ambassador David Hale, how would you describe what the Obama administration, and specifically President Obama's approach was to Israel throughout his presidency?

HALE: Meghna, I was in the room in the Oval Office when that conversation occurred. I had replaced George Mitchell, if I can use that phrase, replaced, a great man, who had left office as special Middle East envoy after two frustrating years.

But I think frankly, we had reached the end of a long trail at that point. And the president's frustration level was sky high. I was in the back of the room with the senior delegation, and you could see steam rising from their ears. So that kind of lecturing, as you said, from the prime minister did not go over well.

I would say that to answer your question, President Obama had a very cerebral approach to the issues. He was not one who naturally developed warm relations. Certainly, it was not a match made in heaven between him and Netanyahu. They had very different world philosophies.

But I think that President Obama is getting a little bit of a bum rap here in that he was very committed to the relationship with Israel, and the strength and depth of the security relationship in particular during the eight Obama years was really quite phenomenal, despite the differences we had over negotiations with the Palestinians and very acute differences over the conduct of our policy toward dealing with the threat of Iran.

Nonetheless, we built a partnership that I think anyone who knows anything about it, values greatly.

CHAKRABARTI: I'm going to ask you more about that cerebral approach in just a minute, but since you reminded us, and I appreciate this a lot, that you were in the Oval Office on the day, on that day in May of 2011, when you were looking at the President. I was just giving you my impression of what I saw on the television footage, but when you were looking at the president, given that you know him and worked with him, what did you see in his response?

HALE: As I said, I felt that it was unexpected, and no one likes, these tend to be fairly scripted moments.

And so there was an element of surprise that, as you said, the president's obviously putting his game face on, but I think again, the frustration that he felt not just at that moment with Netanyahu, but over the overall situation, including with the Palestinians was really very tangible.

And we had just gone through this crisis with the Israelis. As Nimrod mentioned, I was there with the vice president in Jerusalem in March, a few months before. We did work things out quietly. We did get up a no surprises methodology between me and a counterpart in Jerusalem. So we didn't have any more of that going on, but there just had been so much rockiness in the relationship.

And then to have that happen. Not good.

CHAKRABARTI: Yeah.

HALE: But the important thing, we had, in coming back to the day, I don't think the president ever wanted to have daylight evident between him and Netanyahu. And despite these differences, he would always, in my estimation anyway, focus on what's valued in the relationship and what's needed to bring peace and stability to the Middle East.

And he cared greatly about the Palestinian cause. When I was ambassador, if I could just take another half minute.

CHAKRABARTI: Please do.

HALE: I was ambassador to Jordan, when he came out as a senator. And we had every, this was during the Iraq war, Jordan was a platform for a congressman to travel and others into Iraq.

So almost everybody you ever heard of passed through my door. He was the only one who instead of just seeing the Jordanian leadership, asked to go to a Palestinian refugee camp out of hundreds of visitors like that. So this was someone who really cared deeply about finding a solution. And again, the frustration, that for two years he'd been unable to reach that goal was sky high.

CHAKRABARTI: Nimrod Novick, I'm going to come back to you in just a moment, but Ambassador Hale, one more question about the personal relationship between these two leaders. And I very much sympathize that perhaps relationships are not the right place to focus, because it's the policy that comes out of those relationships that matters most.

That's generally where we tend to focus on this show, but of course, if a lot of that policy is shaped by how two world leaders interact, I think it's worth understanding a little bit more. Overall, I'm curious not just how, about how President Obama viewed Israel or the overall Middle East conflict, but did he ever share with you his views of Benjamin Netanyahu specifically?

HALE: I think I don't want to quote the president, leave that to him, but all of us who worked on this issue at a senior enough level were well aware that he was very frustrated with the Israeli approach, and we were trying, and the Israelis were equally frustrated with us. They really didn't think that Abu Mazen was going to respond to the settlement freeze, which the president had set out as a precondition and took us nine months to negotiate.

And they really didn't like the fact that the U.S. administration was constantly lecturing them about how we would take care of Iran. Don't worry about it. We'll take care of it. We'll keep you briefed. Meanwhile, your job is to work on a two-state outcome. And that was not an equation that particular Israeli government felt comfortable with.

CHAKRABARTI: Wow. Okay. Nimrod Novick, here's my question for you about the Obama approach to Israel and how that was viewed by Israelis, of course. Because in that clip that we played, you heard President Obama say that the ultimate goal is a secure Israeli state. And then he goes on to say, not just living side by side in peace. That the Palestinians shouldn't get the opportunity to live only side by side in peace with Israel, but he uses specific language.

He says, "A contiguous, functioning and effective Palestinian state." How did Obama's view on what he would like to see for the Palestinian people fall on Israeli ears?

NOVICK: Israel is hardly homogeneous.

CHAKRABARTI: Yes.

NOVICK: I belong to the school where his words were music to our ears. But that was not the school that was running the country at the time, as David noted.

... I should say the prime minister first and foremost. In Israel, the prime minister is very powerful. The system is not that strong as we've seen in the last year, with a judicial coup that we almost went through. So the prime minister is very powerful, and the prime minister is hostile to the idea of a contiguous Palestinian state, which means no settlements and withdrawn of those that interfere with that contiguity.

From day one, this prime minister anticipated problems with a liberal Democrat of the school of President Obama and joined with the American right in discrediting him even before he was sworn in. Using his middle name Hussein as to suggest that he might be either Muslim or inclined toward sympathy.

There was a campaign to discredit President Obama even before he took office and because Netanyahu is so astute at public manipulation, it worked.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. Wow. Americans are familiar with this, with a similar campaign that took place on the American political right as well here, but it is quite bracing to be reminded that the Israeli right also tried to or looked askance upon the Obama presidency.

But regarding President Barack Obama's view of the Palestinian people, I just want to play a quick, this is from March of 2013 when President Obama gave a speech to an auditorium filled with Israeli university students. Now, of course, the Israeli government itself, as we have explored in the past few minutes, had very different views about settlements and the West Bank and Gaza.

But here is the response that President Obama got from the students that he was speaking to.

OBAMA: And put yourself in their shoes, look at the world through their eyes. It is not fair that a Palestinian child cannot grow up in a state of their own. (APPLAUSE) Living their entire lives with the presence of a foreign army that controls the movements, not just of those young people, but their parents, their grandparents, every single day. It's not just when settler violence against Palestinians goes unpunished. (APPLAUSE)

CHAKRABARTI: So then came 2014 and as both Nimrod and David have mentioned, when Vice President Biden went to Israel and the announcement of radical settlement expansion really caught him off guard and angered him. So Ambassador Hale, you said you were on that trip. Tell us a little bit more about Biden's response and how that then factored into the Obama administration's approach as a whole.

HALE: My recollection is that it was in May 2011.

CHAKRABARTI: Oh, okay. My apologies. Yeah.

HALE: Yeah. And it was, of course, after we had, more or less, where we were giving up on a negotiation the president had invested himself in a fair amount, at least intellectually. And Biden landed and George Mitchell, who was still in office, and I joined him at the King David Hotel for the usual pre visit.

And then Mitchell got on a plane and went back to Washington, and I stayed there to support the visit, although the vice president's people were obviously more getting closer to him. And it was obvious as the meetings began, this announcement of 1,200 housing units being started in Jerusalem was totally contrary to our expectations. A complete surprise.

But the vice president took it, he just took it in stride. And my recollection anyways, both our private briefings and in the public statements, he addressed it with some equanimity. He said, "Yeah, this is bad. But we have to deal with our problems in private. And we will sort this out in public, and then we'll make sure there are no more surprises in the future."

And so Nimrod's, I'm not challenging Nimrod's version that there were differences within the camp, but the policy was set on the fly, which sometimes happens in moments of emergency like this. With the vice president there and confronting this and having to work with the Israeli leadership right there and then.

And as I said earlier, I stayed behind to work out the logistics of communication, once that had been agreed, which I remember as being pretty quick. And there was an acknowledgement on the Israeli side that, "Yep. We shouldn't have surprised you." And we worked a lot to develop a better understanding of how housing units are decided in Jerusalem, which in some cases, Israeli officials themselves didn't fully appreciate.

But one thing I want to mention, because I think it's important. By this point, President Obama had still not visited Israel. So you talk about personalities and emotion and image. And it wasn't, my recollection is it wasn't until the spring of 2012 that he went. And ... Prime Minister Netanyahu had a dinner for him, which was very warm, actually.

The atmosphere was, it was very small, the atmosphere was very positive. They were clearly working on their relationship. So again, I just, I don't want to leave people with the impression that this was an unworkable situation. It was something both wanted to make work.

CHAKRABARTI: Nimrod Novick, I'm wondering, we can't know for sure because none of us are inside Joe Biden's brain, right? This is all to a certain degree speculation. But when Israel decided to go forth with the construction of those apartment buildings, it's proof that no matter how powerful or influential the United States is there's no vessel state out there that's just going to automatically do what any American administration wants.

But I think the presumption was that the close relationship between America and Israel means that some sort of diplomatic warning would be given, or the idea that perhaps there would be discussions beforehand, so that the Americans could gauge how much they'd support it or potential impacts.

It seems like that didn't happen. Do you think that there's any evidence that Joe Biden came away from that meeting thinking maybe we should be a little bit more cautious about how much we trust, especially a Netanyahu government?

NOVICK: Look, as an Israeli, I'd rather focus on trying to understand the implications on this side of the of the ocean.

That is to say when something like this happens, that at least publicly embarrasses the hell out of the Vice President of the United States and the American administration, our greatest friend and ally, the one we are totally dependent upon for virtually everything. Yeah, we are a sovereign country, and we make the decisions ourselves, but to ignore American interests, to do it in such a blunt way, and worst of all, in my judgment, and get away with it.

The very fact that David managed to work out a mechanism to avoid such occasions in the future was well worth it. But what is the lesson learned by Netanyahu? You can really defy Washington and get away with it.

Part III

CHAKRABARTI: Ambassador Hale, let me quickly ask you, what do you think the administration's successes have been in the past couple of months with the Biden approach as we've seen it so far.

HALE: The successes are, clearly the strong relationship with Israel is even stronger. And I think there's widespread, Nimrod can address it, but widespread appreciation for the integrity and stalwart nature of that. The second, I think they've done a good job in building support in the G7 for that approach.

Even though, as always, there are voices that would like to see a ceasefire immediately. I think the administration has done a good job in communicating to them that a ceasefire doesn't actually result in eliminating Hamas's ability to fight, is no real ceasefire that's worth having.

Harder to tackle the question with Arabs, and with others, about what the day after is going to look like. And that really is where the American role should be strongest, is shaping what comes next. And that obviously, the diplomacy is not going to be too public, but we haven't seen yet, at least I haven't seen yet, a workable concept that's going to meet Israeli security needs and build lasting stability.

CHAKRABARTI: Nimrod Novick, there are other things specifically that have happened in the past month or so that we in the public can point to as temporary successes, right? Of course, we had the release of some hostages in exchange for the release of Palestinian prisoners. There have been humanitarian supplies or trucks that have entered Gaza.

And we did have those pauses for a little while. And these are specific things that Biden himself and the administration have asked for and helped work towards. But there are other things that simply there, there seems to be no progress on, right? The United States and lots of other countries are asking very vociferously now for the Israeli military to try to avoid civilian casualties in Gaza.

And then there's also the question of reining in settlers. What do you make of that? Has Benjamin Netanyahu been just very point blank resisting those particular?

NOVICK: I wish he were resisting them for good reasons. I'm afraid that's not the case. Let me put it this way. On day one, day two, day three, after the horrific brutal Hamas butchering of Israelis in our south, there was no day like, as you noted, no day like between the Biden administration and the Netanyahu government.

But here we are day 60, 61, and we have two clusters of major differences. And the administration can no longer keep them private, and even accentuate them in an effort to get some move on the Israeli side. One is operational on the conduct of the war, and both you and David mentioned it. The humanitarian relief that Netanyahu was so stingy and still is very stingy about the humanitarian corridor that he resisted and eventually accepted, the issue of the way the idea of conduct itself in terms of civilian population and non-combatants.

And so on. And that's about the conduct of the war. And at the same time, things are going from bad to worse in terms of Jewish terrorism on the West Bank, threatening to ignite that area as well. But there's also a cluster of strategic issues. Here we have the administration putting together a concept that is supposed to pacify and stabilize Gaza, for the morning after. Concurrent with stabilizing the West Bank and launching something long term, off a political horizon over there.

Both resting on two prerequisites, one that it's all sponsored by the Palestinian Authority. Initially, given its miserable state at the moment, initially, symbolically, granting legitimacy to whoever, whatever third party takes over Gaza after the idea of withdrawals.

But eventually, after it rejuvenated a year, two, three, as long as it takes, then the PA substantively takes over Gaza as well. And the second condition that every country that Secretary Blinken has approached, to contribute to the morning after strategy, they all have both conditions. One, it's sponsored by the PA. And two, it is part of a broader political horizon, political process.

And on both of them, Netanyahu says no. And there's no go for the morning after strategy, as long as there's no change in policy in Jerusalem, and I'm afraid that given Netanyahu's total dependence on the most extreme elements of Israeli society, that he gathered together in his current coalition, because they were the only ones who were willing to commit to help him find a way out of his legal predicaments.

His total dependence suggests that to change policy in Jerusalem, you got to change government.

CHAKRABARTI: Ah, okay. You know here, as both of you well know, here in the United States, everything that Nimrod just described has led to very high-level members of the Biden administration to say more and more directly about these aspects in which Benjamin Netanyahu is not compromising at all.

And this has especially been happening in the past just a couple of weeks. So let me just play a little bit of tape here from Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin. Now, this first bit is going to be from last month when he flew to Israel for meetings with the Prime Minister and Israeli defense officials.

And at that meeting, once again, he reiterated the U.S.' support for Israel's effort to defeat Hamas.

AUSTIN: I am here in person to make something crystal clear. America's support for Israel is ironclad now, this is no time for neutrality or for false equivalents or for excuses for the inexcusable.

There is never any justification for terrorism.

CHAKRABARTI: So once again there, you hear the defense secretary very clearly saying the United States supports the goal of Israel defeating Hamas. But the how that the Israeli military has been going about doing it, that's raised some more vocal criticism now from the same people we've been talking about. Because just a few days ago, in a speech to the Reagan National Defense Forum in California, here's what Secretary Austin said.

AUSTIN: In this kind of a fight, the center of gravity is the civilian population. And if you drive them into the arms of the enemy, you replace a tactical victory with a strategic defeat. So I have repeatedly made clear to Israel's leaders that protecting Palestinian civilians in Gaza is both a moral responsibility and a strategic imperative.

CHAKRABARTI: Here's one more. This is the United States Secretary of State, Antony Blinken. He was in Tel Aviv just a week ago, basically issuing the similar warning, that the Israeli government should not move its operations towards devastating southern Gaza the way it has devastated northern Gaza.

BLINKEN: We discussed the details of Israel's ongoing planning, and I underscore the imperative of the United States, that the massive loss of civilian life and displacement of the scale we saw in northern Gaza not be repeated in the south. As I told the prime minister, intent matters, but so does the result.

CHAKRABARTI: Ambassador Hale, presumably when cabinet members speak out so clearly in public, it means that similar discussions have been going on for some time behind closed doors. But what's your read about the fact that now Austin, Blinken, and we heard the Vice President, Kamala Harris, a little bit ago, saying these things out loud and so clearly now.

HALE: It's obviously a coordinated messaging. I think that the administration's remarkably disciplined in this chapter. I think I'd like to widen the aperture just for a second. This is a pattern that we've all seen, going all the way back to Ronald Reagan and Menachem Begin and the siege of Beirut.

And it's utterly predictable, I think it was anyway on October 7th, that we would have strong U.S. support, that Israel would undertake a really spectacular, I don't mean that in a negative or positive way, but just a shocking offensive to deal with Hamas. That because of the asymmetrical nature of the conflict, and the fact that Hamas was using Palestinian people as human shields, there would be very sizable casualties.

We know this from past wars, and all this was utterly predictable. And we would know that it would only be a matter of weeks before public opinion outside Israel would start to turn on Israel, and that would create a political problem. Not just a diplomatic problem for this administration, as we've seen.

And you'd have to ask them whether that takes, what extent the administration's addressing its own constituency, as well as decision makers overseas. The other, the next predictable chapter is that when this conflict will end, that we will wake up one morning and it will be over. But how are we going to deal with the day after when the actual protagonist here is Iran?

It's fine to talk about getting the Palestinian Authority back into Gaza. It's fine to talk about the two-state solution. This is not a moment in which you want to abandon those things. But they're irrelevant because we're dealing with Iran and its proxies here, as is Israel. And they don't want peace.

This is what, the raison d'être is to do everything to prevent us from achieving that goal.

CHAKRABARTI: That's a point very well taken, Ambassador, because, of course, none, as you said, none of this is happening in a vacuum. There's a much larger diplomatic issue, not just diplomatic, but security issue to be dealt with here, but that's actually why the change in tone from the administration, if not the president himself, a lot, and directly.

That's why it's so interesting, I think, right now, because I want to play a couple of other quick examples here. This is actually former President Barack Obama. He very recently spoke to a live audience. It was for a recording of the podcast, Pod Save America. And in this recording of the podcast, Obama said the solution for Israelis and Palestinians alike is not for the U.S. to show absolute support for one side or the other.

OBAMA: If you want to solve the problem, then you have to take in the whole truth. (APPLAUSE) And you then have to admit nobody's hands are clean, that all of us are complicit to some degree. I look at this and I think back, "What could I have done during my presidency to move this forward, as hard as I tried?"

I've got the scars to prove it. But there's a part of me that's still saying, "Was there something else I could have done? "

CHAKRABARTI: Interesting. Obama, there saying that to solve what seems to be an intractable and terribly bloody problem, leaders have to admit nobody's hands are clean. That didn't really meet with a lot of enthusiasm from the current Biden administration.

They spoke out with expressing their respectful disagreement on that. But here's another voice of many that have been increasing his criticism of the Biden administration. Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, and he last week had this to say about how the president has tried to influence Israel.

BERNIE SANDERS: The Biden administration has appropriately, and I applaud them for this, been trying to get the Israelis to be more targeted in their approach. But there is little evidence that they have succeeded. And the truth is that if asking nicely worked, we wouldn't be in the position we are today. Asking nicely just is not going to bring about the kinds of changes that are needed.

CHAKRABARTI: Nimrod Novick, we only have two minutes left. So what might the Netanyahu government or the Prime Minister himself feel that the United States could do, given this increasing criticism of the very close relationship of the United States and Israel? Or, as you said earlier, if Netanyahu learned from the Obama administration that he can do what he wants with no consequence.

Does it matter how the U.S. changes its approach at all?

NOVICK: Exactly. There is the unavoidable and there is the avoidable. Civilian casualties are unavoidable, and I believe, contrary to some criticism worldwide, that the idea of conducting itself as carefully as any army ever in that regard, the setting is impossible.

And I don't need to elaborate. You mentioned it earlier. But what is avoidable is haggling over every truck of humanitarian assistance. The prime minister of Israel should have been the one who is leading, doubling the international demand for humanitarian supplies, humanitarian corridors, and all that. Here is the administration telling the Israeli prime minister, "We want to help you, but we need you to help us help you."

You need the time for the IDF to complete its mission. We believe in that mission, but en route, you got to do certain things that make it possible for us to help you. And here is the prime minister, totally dependent on more, most extreme elements of his coalition, chooses his coalition over his relationship with Washington, and possibly the possibility of accomplishing the mission in Gaza.

This program aired on December 7, 2023.