Advertisement

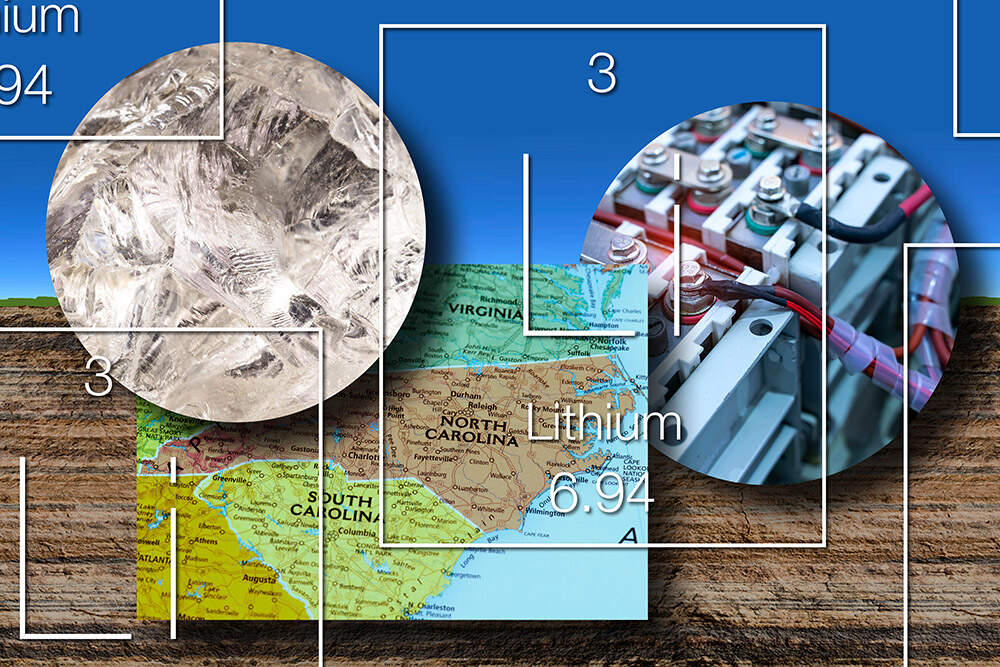

The lithium boom: What's holding back a lithium rush in the U.S.?

Resume

The U.S. sits on some of the largest lithium reserves in the world.

It’s a key element for clean energy.

Today, On Point: The start of On Point’s weeklong exploration “Elements of energy” takes us inside America’s push for a lithium boom.

Guests

Scott Lake, Nevada staff attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity.

Also Featured

Daranda Hinkey, co-founder of People of Red Mountain, an activist group working to protect indigenous lands from the impact of mining. Member of the Fort McDermitt Paiute Shoshone Tribes of the Fort McDermitt Indian Reservation in Nevada and Oregon.

Larry McDaniel, Kings Mountain, North Carolina resident who worked at the city’s lithium mine and processing facility for 38 years.

Daniel Greene, Kings Mountain resident who worked at the city’s lithium mine and processing facility for 45 years.

Jim Palenick, city manager of Kings Mountain, North Carolina.

Raef Sully, CEO of Lilac Solutions, a California-based lithium extraction company.

Transcript

Part I

MEGHNA CHAKRABARTI: Elements of energy: Mining for a green future. Welcome. All this week, we are taking a detailed look at four elements critical for a clean energy economy.

Today, it's episode one, the lithium boom. What's holding back a lithium rush in the U.S.?

Ernest Scheyder is author of The War Below: Lithium, Copper and the Global Battle to Power Our Lives. He’ll be with us throughout the week with quick primers on each element.

ERNEST SCHEYDER: Lithium is the lightest metal on the periodic table of elements. It’s also very good at retaining an electric charge. That makes this white-colored metal the perfect anchor for the lithium ion battery. Chile and Australia are the world’s largest lithium producers, and China is the world’s largest lithium processor.

CHAKRABARTI: But when it comes to lithium that’s still in the ground, it’s the United States that has some of the largest lithium deposits in the world. At least 14 million metric tons, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

A lot of those deposits are in Kings Mountain, North Carolina. Population: Roughly 12,000. Nestled in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, about 30 miles west of Charlotte.

From 1938 to 1988, lithium from Kings Mountain was a key ingredient in a whole range of global products. Things like ceramics, glass, pharmaceuticals, pacemakers and paints. For about 30 years, the region supplied almost all the lithium in the world.

DANIEL GREENE: I grew up in Kings Mountain, right outside the mine.

CHAKRABARTI: Daniel Greene is retired now, but he was 20 years old when he got his first mining job in 1972. Back then, it was owned by the Foote Mineral Company.

GREENE: They would drill 20 foot [sic] deep. And then they'd drop dynamite down in it, pack the dynamite and all, and then when they blasted, it’d bust all that rock loose and then they could get it out of the mine and everything.

CHAKRABARTI: Daniel and his team were looking for rocks containing spodumene. It’s a greenish-white mineral with high concentrations of lithium. North Carolina is home to one of the richest deposits in North America — a one-mile wide, 25 mile-long band called the Carolina Tin-Spodumene Belt.

GREENE: Anytime you mess around in a mine like that, you know, it gets kind of dusty because you're busting up rocks and everything like that. But it is a great place to work. There's all kinds of minerals there and all.

CHAKRABARTI: Larry McDaniel started working at the mine in 1975.

LARRY MCDANIEL: We were still using the old cable shovels. The largest truck we had was a 35 ton haul truck. We had dozers and loaders, etc. I just enjoyed working on big, heavy equipment.

CHAKRABARTI: He followed his dad, who’d worked there since the 50s.

MCDANIEL: I guess you could call me a lithium brat. You know, kind of like a military brat. (LAUGHS)

CHAKRABARTI: Larry and Daniel worked together for years. Daniel even shared the nickname Larry has around Kings Mountain.

GREENE: (LAUGHS) Oh, Stub? He was so short and all, that's what everybody called him all the time.

CHAKRABARTI: But by 1988, lithium demand dropped. The Foote Mineral Company shut down the Kings Mountain mine. Deposits in Chile were cheaper to extract.

MCDANIEL: In Kings Mountain, you had to drill it, blast it, crush it, run it through the mill, mill it, then go to a lithium hydroxide process. Where it was costing us, say, $1.70 a ton to make lithium hydroxide, we could do it in Chile for about 50 cents a ton.

CHAKRABARTI: Foote Mineral closed the mine, but the Kings Mountain lithium processing facility remained open. Today, less than 1% of global lithium is mined in the United States, all from Nevada, which we’ll hear about later.

The old Kings Mountain mine has completely changed. It's now a hundred acre lake, surrounded by trees and hiking trails. Leftover mining rubble makes up a steep climb that locals call Cardio Hill.

GREENE: It was like 560 people in the heyday. And then had a massive layoff when we shut the mine down. We kept just struggling along and everything. But we let the mine fill up with water.

CHAKRABARTI: Sounds like the familiar tale of an American community, once home to important industry and good jobs, abandoned for cheaper materials and labor abroad. That could have been the end of the story for Kings Mountain. But, it’s not.

ERIC NORRIS: This is such a special occasion for us.

CHAKRABARTI: This is Eric Norris, head of the Energy Storage business unit at the Albemarle Corporation. The company acquired the Kings Mountain mine in 2015. Norris was speaking at a town hall in March 2022.

NORRIS: Kings Mountain could supply a million to a million and a half electric vehicles.

CHAKRABARTI: Albemarle is a specialty chemical manufacturing company headquartered in Charlotte, North Carolina, not far from Kings Mountain. It’s the world’s largest lithium producer. For years, Albemarle used its Kings Mountain site to process lithium extracted in Chile and Nevada. And now, Albemarle plans to reopen the mine. Why?

Though still volatile, global demand for electric vehicles continues to rise.

As a result, the price of lithium has skyrocketed. In 2022 alone, lithium prices shot up by 400%, reaching as high as $50,000 per ton. There have been corrections since then, primarily due to decisions made in the Chinese EV market. But Albemarle is still betting that the clean energy push will make the Kings Mountain mine a winner once again.

Albemarle declined our interview requests. But it’s said the mine will create 300 jobs and could open as soon as late 2026. Here’s spokesperson Cindy Estridge in a video produced by the company.

CINDY ESTRIDGE: It’s gonna take us 18 months to dewater this pit because we’re gonna do it very slowly. We could do it much faster but this is going into a small, local creek called Kings Creek, and we don’t want to erode the banks of the creek by doing it too quickly.

JIM PALENICK: You're talking about these 1,800 acres of otherwise developable lands that can't become industrial parks, new residential subdivisions, new commerce. Rather, they will be simply a very large hole in the ground.

CHAKRABARTI: Jim Palenick is Kings Mountain city manager. He supports reopening the mine. But he says if Kings Mountain is going to play a major role in America’s clean energy future, he wants more benefits to stay in his community.

PALENICK: Yes, Albemarle will take some spodumene concentrate out. They'll sell it for a large amount of money. They'll process it in a new plant that they're building well down in Richburg, South Carolina for $1.3 billion. They will take all of their research and development professional employees out to Charlotte. And pretty much the only thing the city of Kings Mountain gets out of this is being the host community for this very large mining operation.

CHAKRABARTI: Palenick wants to make sure Kings Mountain gets properly compensated. He points to the substantial federal funding Albemarle Corporation has already received.

PALENICK: The federal government, so they have said nationally, it's important enough for us to give this private corporation $240 million. That's because the rest of this country is going to benefit from the product that they produce. If this is worth 240 million of subsidy going to you, is that also worthy of paying that amount for the negative side of it coming back?

CHAKRABARTI: He’s also cautious about repeating history’s mistakes.

PALENICK: I really feel for sort of those West Virginia coal communities where, you know, you have a big open pit mine. They got great value, took it outta the ground, but not that much ever comes back to that poor, you know, West Virginia coal mining community. So we want to take a lesson from those and say, you're not gonna leave this community that way.

CHAKRABARTI: For Larry McDaniel, who started out operating cable shovels in the Kings Mountain mine in 1975, his mining experience has led to recent consulting jobs with Albemarle. We asked him for more detail. He declined.

But Larry does say this: Kings Mountain was a mining town for some 70 years. When the mine shut down, it hurt. Lithium is often called “white gold”, for its silvery color and high price. McDaniel says, it’s high time that gold rush got started again.

MCDANIEL: I think it's a fantastic decision. I mean, we did from 19 — well, let’s see, Dad went to work in 1951. And from 1951 to about 1984, when we started winding down the mine, it went on on a daily basis. Nothing different than what Albemarle is proposing now. Kings Mountain is not going to be losing out. It's actually going to be gaining.

Part II

CHAKRABARTI: You're back with episode one of our special series, Elements of energy: Mining for a green future. And today we are looking at the lithium boom. As you heard, the United States has some of the largest lithium deposits in the world, but less than 1% of global lithium is currently mined in the United States.

That's poised to change, because the domestic market for lithium is roaring back.

JOE BIDEN: See that sucker over there? 0 to 60 in 4.1 seconds. It's all electric. I tell you what.

CHAKRABARTI: August 5th, 2021. President Biden stood on the South Lawn of the White House, backed by fresh off the line electric versions of popular American cars.

That day, Biden signed an executive order calling for more ambitious vehicle emissions standards and for electric vehicles to make up half of all new vehicle sales in this country by 2030. The heads of automakers Ford, GM, and Stellantis joined Biden at the White House, and during the speech, he glanced over at General Motors CEO Mary Barra.

BIDEN: And I want to say publicly, I have a commitment from Mary, when they make the first electric Corvette, I get to drive it, right Mary?

CHAKRABARTI: In March of 2023, GM formally introduced the all-electric Corvette E-Ray. It touts a six-figure price tag. And don't know if he's ever driven one, but Biden did climb into an orange electric Corvette at the 2022 Detroit Car Show.

More importantly, Biden's administration is the first to directly tie electric vehicle goals to primary source mining in this country. The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act comes with hefty EV tax credits, but they only apply if the materials used to make the vehicles, batteries included, come from the United States or nations in free trade agreements with the U.S.

Hence, the vast sums of federal funding such as the $240 million dollars that's already gone to Albemarle Corporation in North Carolina for lithium mining. Joining us now is Scott Lake. He's Nevada staff attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity, and he joins us from Reno. Scott, welcome to On Point.

SCOTT LAKE: Thanks Meghna.

CHAKRABARTI: So first of all, tell us from your perspective, do you think that the clean energy revolution, I should say, that the Biden administration has envisioned, will be possible without a massive increase in lithium mining in the U.S.?

LAKE: I think we are going to need to produce some lithium domestically.

And that's something that we, at the Center for Biological Diversity have acknowledged for a long time. So minerals are going to be necessary for changing our transportation system and adapting to climate change. I think the question we're facing now is, is this going to be business as usual mining, which has had devastating impacts on communities and landscapes throughout the world, or are we going to have a different approach where we prioritize mining techniques and locations that have fewer impacts?

CHAKRABARTI: Just to get a sense as to how much might be in the pipeline in terms of the expansion of mining, particularly in the Western United States. When we spoke with your colleague, Patrick Donnelly, he described the coming expansion of mining activity in the West as so large, it makes the gold rush pale in comparison.

He says it could be for, specifically for lithium, it could be the largest expansion of mining activity in the history of the Western United States. Can you describe essentially what's in the pipeline or what's planned for lithium mining just in Nevada alone?

LAKE: Sure. Patrick is absolutely right. The scale of this proposed lithium rush makes the gold rush really pale in comparison.

There are 83 lithium mine proposals in Nevada alone. And there are 130 across the West. If even half of these get built, it would be the most dramatic expansion of mining activity in the history of the West. And as I mentioned earlier, some of these projects at least could have some devastating impacts on both ecosystems and communities.

It's a really complicated matter though, because with that dramatic expansion of mining comes, ideally, jobs and this essential element for the batteries that are going to make up the clean energy future.

CHAKRABARTI: Can you tell us a little bit about the practices, the current practices for lithium mining in Western sites?

How is it extracted from the ground and then refined into usable lithium?

LAKE: You basically have two ways of getting lithium out of the ground, two fundamental ways. One is your traditional open pit clay mining. And that's the kind of mining you've heard about already on the show. The other is brine extraction, where you have the salty water that's been deposited in subterranean aquifers.

You can extract that water, and then extract lithium from that water. Those are basically the two kinds of lithium extraction that we have today. The Albemarle plant here in Nevada is a brine evaporation operation. So what they're doing is they're pumping brine out of the ground. About 3 to 6 billion, that's with a B, gallons of water are pumped at that operation per year.

And the water is essentially evaporated off, which leaves behind salt deposits, which are then processed into lithium. That's the same kind of extraction that we generally see in South America, which is where most of our lithium for the American market comes from today.

CHAKRABARTI: Every time you pick up a phone, for example or drive an EV that's already out there, you're definitely driving with, using some lithium that you said has come from, primarily from Chile.

Like, how large are these brine evaporation areas that the lithium mining processes use?

LAKE: They're massive. It's a huge land use commitment. And I don't have an exact figure for you, but I can tell you that both here in Nevada and in South America, you can look at Google earth and then see these things pretty clearly from the satellite photos.

So it's a significant use of space.

CHAKRABARTI: Now, so we're talking about brine, right? So it's not fresh groundwater, but it's groundwater nonetheless. Is that right?

LAKE: That's right. And you have in a lot of these places, aquifers in layers. So the lithium operations will generally pull from the brine layer, but that doesn't mean that they aren't all interconnected.

What we've seen at the Silver Peak facility, for example, is that even though that's extracting brine, it has caused the freshwater aquifers in the area to drop.

CHAKRABARTI: And has there been any visible or not just visible, but environmental impact from that drop?

LAKE: Yes, the groundwater level and wells has gone down and springs have gone dry.

This isn't an area that has a whole lot of human habitation or a lot of groundwater dependent ecosystems at this point. It's not an area that's having the kind of impact that we are mostly concerned about. It's not a place where, for example, a species is threatened with extinction, but there are environmental impacts from that mining.

CHAKRAARTI: Okay, but just in that location, that part of Nevada, as far as I understand, there are, what, 50 to 60 more proposed brine projects for that area. Is that right?

LAKE: Not necessarily for that area specifically, I think what we're looking at is a 50 to 60 projects. And when we can talk about this too, 50 to 60 projects using direct, with the extraction technology. And that's a recent technological development that really hasn't been used at a commercial scale yet. But shows promise.

So about, of those, about 130 projects they mentioned earlier, about 50 to 60 of those are direct lithium extraction or DLE.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, so actually this is our opportunity to learn more about this process which is different than the brine evaporation or open pit mining, I think that you talked about before.

And I just want to emphasize what you said. It hasn't been used at scale commercially yet, but looks like there's a lot of places that are interested in using it. So what is it? In order to find out that answer, we spoke with Lilac Solutions. It's a startup that was founded in 2016. It's based in Oakland, California.

CEO Raef Sully says Lilac uses a process called direct lithium extraction.

RAEF SULLY: We bring the water out of the brine, the salt water from underground, we pump it up, it runs through the DLE unit, we extract the lithium, and then we pump the water back down.

CHAKRABARTI: So obviously the big difference there, no massive evaporation ponds, just tanks that are filtering out the lithium from the brine.

And Sully says Lilac Solutions' process depends on a special kind of bead.

SULLY: You have a bead or a resin, which is a metal oxide. I can't tell you the secrets of our beads, because that's what makes us special, but they have a propensity or a selectivity for lithium. So as the brine washes over, our beads absorb the lithium out of solution, and then we wash the beads to extract the lithium, and the brine goes back into the ground.

CHAKRABARTI: Now, Sully says this method is better for the environment than open pit mining or evaporation. He claims it may also be cheaper. But now, to emphasize again, no company is yet using DLE at a commercial scale. But Sully says Lilac Solutions did have success with a demonstration plant in Argentina.

SULLY: The thing you need to realize about a demonstration plant is that the internal workings, so the vessel that holds the beads, is about one third the size of the vessels that would hold the beads on a commercial scale.

On a commercial scale, we would have many more of these side by side. The next step for us would be a small commercial facility where we would look to try and produce somewhere between three and 5,000 tons in a year.

CHAKRABARTI: Sully says he hopes Lilac Solutions is only a couple of years away from that small commercial facility. They just raised $145 million for some big-name companies such as Mitsubishi, BMW, and Bill Gates' clean energy fund called Breakthrough Energy Ventures. So that's where the money came from. And where this new facility might be?

Sully says Lilac is eyeing Utah's Great Salt Lake.

SULLY: That's the most likely position for the moment. I think we will develop the Great Salt Lake. I don't know whether it's the first one we do. Or the second one. At the moment it looks like it's going to be the first one. There are a couple of other conversations we're having.

I just can't disclose who they're with or where they are. But certainly, I think Great Salt Lake is very likely to be the first one we do. It will happen. It's a good resource. It does need our technology though. Other DLE technologies are not as capable at lower concentrations as ours is.

CHAKRABARTI: Once the direct lithium extraction facility is built, whether at the Great Salt Lake or elsewhere, Sully says this is what it will look like from the outside.

SULLY: An industrial warehouse, I think, is the best way. It's going to be enclosed in a warehouse. There'll be a pipe in and a pipe out and a car park and maybe an office building and some cars in the car park. It probably all fits within a five-acre block.

CHAKRABARTI: That's Raef Sully, CEO of the lithium startup Lilac Solutions based in Oakland, California.

Scott Lake with the Center for Biological Diversity in Reno. Is there a bit of a mismatch in timing here. That if this one particular DLE startup says they still actually haven't had a commercial scale processing facility successfully constructed. Is there a mismatch between that and the fact that you just said that 50 to 60 of the proposed lithium mining operations in Nevada are thinking that they're going to use DLE.

LAKE: I think there are 2 things going into the number of projects we're seeing.

One, as you mentioned earlier, is the price of lithium. It's just made, the high demand, the high price means that we have a lot of projects, whether those projects are ultimately viable or not, I don't know, that will be seen in time. And I think what is also reflects, though, and this might be the more important point is that DLE is an extremely promising technology. It could really be a kind of silver bullet where you don't have to have the sort of land impacts that you have with an open pit mine. You don't have to waste billions of gallons of groundwater and an evaporation operation. It can be a lot more efficient.

It could potentially be cheaper. So in a lot of ways, DLE could solve some of the problems we're seeing with lithium extraction and resolve some of these conflicts now. That does depend on whether it can be deployed on a commercial scale, but I think the reason you're seeing this interest is because, the first company, the first few companies that are able to do this are probably staying to make a lot of money.

CHAKRABARTI: So tell us a little bit more about what the statewide perspectives are on the lithium boom that looks like is coming to Nevada. Who are the different stakeholders and what do they have to say about the hundred, or actually across the West, it's more than 100 projects, but the dozens of projects lined up for the state of Nevada.

LAKE: I think on one hand, you have the state and the federal government really getting behind lithium extraction and really not discriminating very much between methods or locations. It's definitely something that's being encouraged by both the federal government and local government. On the other hand, you have, organizations like ours concerned about the environment communities that could be impacted. Native American communities and farming communities. From some of these impacts you've already discussed, including open pit mining and groundwater depletion and pollution potentially.

It's really a balancing act. I think our position has been that we don't want to be fighting lithium mines all day. And we think the solution is some proactive planning that it prioritizes development in areas where these conflicts are not going to occur. Areas where you don't have groundwater dependent ecosystems, areas where mining is not going to impact local communities.

And some of this technological innovation we've heard about could definitely play a part in that.

CHAKRABARTI: What's your overall take on the cost benefit of the need for lithium for a more electrified future versus the impacts that you just talked about. Is there any way to balance them?

LAKE: We think there is. There absolutely is a way to have both. I think the thing to keep in mind is that in addition to the climate crisis there is an equally pressing biodiversity crisis with species going extinct at an extraordinary rate. And in addressing the climate crisis, we don't want to exacerbate the biodiversity crisis, which in the long term threatens our future just as much.

We have a choice to make here. Are we going to do this, like I said earlier, as business as usual, or are we going to do this differently with the benefit of some of these lessons we learned in the past? I think it can definitely be, this can definitely be done in a way. Where the benefits are maximized, and the costs are minimized.

Part III

CHAKRABARTI: Today we're talking about the lithium boom in the United States. It's obvious to say, but we're saying anyway, a highly electrified future cannot happen without a rapid increase or a massive increase in lithium mining, particularly here in the U.S. Now, we've talked about lithium in hard rocks in Kings Mountain, North Carolina. We've talked about lithium extracted from brine in Nevada. And the fact is that those are two examples of a nationwide issue for the Indigenous peoples of the United States. Because most of the places where lithium is being mined or could be mined in the future in this country are located within 35 miles of Native American reservations.

That's according to a 2021 report from the investment research firm MCSI, and they took a look at some 5, 300 mining properties in the U.S. and found that near proximity to indigenous lands. The report also found that most U.S. reserves of other elements that we'll be talking about this week. Copper, cobalt, and nickel, are also within 35 miles of reservations as well. So obviously this is a major issue for indigenous tribes in the United States. Scott Lake is still with us. He's Nevada staff attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity. He's in Reno. And Scott, let's listen to a quick comment from Kate Finn, who's the executive director of First Peoples Worldwide.

The organization's goal is to quote "work from a foundation of Indigenous values to achieve a sustainable future for all." We'll hear more from her a little later this week. And she told us, for today's show, that the perception that tribes are unilaterally opposed to mining is incorrect.

KATE FINN: The goal for us at First Peoples Worldwide and so many different organizations. And many folks working for and with tribes in the U.S. is sovereignty. So the ability for a tribe to have the first say about what happens in their community and how it happens. There are a number of tribes who are actively building solar panels, actively exploring wind. And there are tribes who will actively seek to have mining on their territories.

The point is that tribes have the ability to say yes or no.

CHAKRABARTI: So Scott since you're there in Nevada, I'd love to learn more specifically about one of the biggest mining projects there that has really had an impact already on indigenous communities. And that is in Thacker Pass. Can you tell us a little bit about that?

LAKE: I can, I am just going to warn you that this is not something that the Center for Biological Diversity really engaged on. So I haven't been personally involved in this. I do know quite a bit about the context. So I'll do my best. But basically, the Thacker Pass mine is your traditional hard rock, open pit mine.

It's being built as we speak in northern Nevada on the historical lands of the McDermitt Paiute-Shoshone tribe and several other tribes as well. And I know that there's been quite a bit of controversy about this. The situation, as you suggested, is complex. The tribal government at one point supported the mine, local tribal members formed a coalition to oppose it.

There's been opposition from environmental groups and also from local ranchers as well. But I think the overall point of this is that the impacts to this local community are going to be pretty severe. And people are recognizing that. And I think the broader point is that with projects like this. With these high conflict projects, the local communities are not going to take this stuff lying down.

There's going to be resistance. They're going to try to protect their community. Ultimately building without the consent of the community or building in places where you have a lot of impacts, I think is slowing down. Paradoxically, the green energy transition. And if we were to prioritize areas that were less conflict prone, less impactful, then we can conceivably do this a whole lot faster and spend less time in court.

CHAKRABARTI: We've spoken with several members of Indigenous communities, particularly in and around Nevada. Daranda Hinkey is co-founder of People of Red Mountain, and it is an Indigenous community.

She's also a member of the Fort McDermitt Paiute-Shoshone Tribe in Nevada. She talked to us about Thacker Pass, and she says one of the major objections that the Indigenous communities have to expanded mining in Thacker Pass is that it is a sacred and historical site for Native people.

DARANDA HINKEY: They put that Fort McDermitt military post there.

That was in 1865. And a month after, so August 1865, a month after September 12th, 1865, is when U.S. Calvary came over. And that's where they massacred a band of Paiute-Shoshone people. People of our mountain, we come back to that spot annually.

CHAKRABARTI: So as Daranda said, the group goes back every year to commemorate the lost souls in that massacre.

So that is why it is considered sacred ground for them. And in fact, other members of surrounding indigenous communities call it cultural genocide to expand lithium mining there. So Scott, again, suppose from a more 30,000-foot level, can you talk to me a little bit more about the process or what an ideal process would be to take seriously. And take into account the cultural concerns of indigenous peoples, when thinking about, if any or expanded mining should be done in places all over Nevada.

LAKE: One important thing is something that we've discussed already on the show, and that's having free prior informed consent of those communities. That's something that our current mining law really doesn't provide. And that's a big problem. I think that's where a lot of these conflicts originate.

And as I mentioned before, I think a planning effort that really looked at a lot of these values globally and cumulatively would help in this. You would look at places where, for example, you have species threatened with extinction, or you have sensitive ecosystem.

You'd also look at areas that are important or sacred to Native American tribes. Areas that are important to other local communities and put that all in one place. So that we know where these communities are going to be okay with development and where they're not. And we do that before these projects are proposed. And before all this investment comes in, that really locks both the industry and the government into one particular course of action.

CHAKRABARTI: Can you help me understand if that, if any part of that process is already in place? Because ... an analogous process would be environmental reviews. Which would have to happen whether they're performed both by the federal government and by state, local and governments and the mining companies themselves.

Are there sort of cultural reviews as part of a process to approve new lithium mining?

LAKE: There is what you might call a cultural review under the National Historic Preservation Act. It's a process called consultation. It's pretty minimal, a lot of times it adds up to basically a letter sent to a tribal government, maybe a few in person meetings.

It really doesn't end up substantively impacting the outcome very much. So I think that's one thing that the tribes in particular are very concerned about. Is that they have this opportunity to raise their concerns, but ultimately that doesn't really change the outcome. So even when you're dealing with projects like Thacker Pass, where it's impacting an actual sacred site. That tends to really not change the course of things very much.

And I think that's really why some of these communities are upset.

CHAKRABARTI: So a little bit more of the background to the Thacker Pass development. I believe it is the largest known lithium deposit in the United States. So it is a very, not just culturally precious land for indigenous peoples there, but in terms of what could be extracted from the ground, it's virtually unique in the U.S., given its size.

Now, it was in January of 2021 that the Bureau of Land Management made a decision to approve the development of the mine. Construction began there in the spring of 2023, though there were court efforts to stop that construction. Interestingly, and this takes us back to the close link between the Biden administration's desire to increase electric vehicle production and a clean energy future.

The mine is a project of a company known as Lithium Nevada, LLC. It's owned by Lithium Americas Corporation. We'll hear from someone from that company in just a moment. In January of 2023, General Motors announced that it would invest $650 million in that mine project, basically giving GM exclusive access to the first phase of production of lithium out of the mine.

And GM is the largest shareholder in Lithium America's corporation. So keep that in mind. And we're going to listen to a few more of what indigenous peoples in the region have to say. So this is Arlo Crutcher, who's chairman of the Fort McDermitt Paiute-Shoshone tribe in 2023 with a television station, 2 News Nevada.

He said, yes, the mine is moving forward. And the tribes will have to learn to live with it.

ARLO CRUTCHER: I consider myself sitting in the middle of the fence, because I represent all the people. How do we deal with something that came into place, that's in place, that's going to be there? Just like everything else in life, it forces us to make adjustments within our lifestyles.

CHAKRABARTI: Now he also told TV Station 2 News Nevada that there is a community agreement in place that the tribe signed with Lithium Americas. And it included some good things, like a new community center. And he also hopes that the mine will mean more local jobs.

It's a positive move because we do have an old headstart building here that's not in very good shape.

A lot of our people are forced to move out, because of not having the work around here. Give them the opportunity to come home, get closer to home, put in for jobs here.

CHAKRABARTI: Jobs obviously a very important need for indigenous communities as well. But as we've said, this isn't just a one group has one opinion about lithium, another group has another.

Nothing is that simple here. And to understand the sometimes-conflicting nuances, listen to Arlan Melendez, chairman of the Reno Sparks Indian Colony. He also told TV Station 2 News Nevada in July of 2023 that community center and jobs are not enough. He says painful things happened at Thacker Pass.

ARLAN MELENDEZ: Our tribe would think it might be empty physically, but it's not empty spiritually. It's our ancestors that are still there or haven't been settled because of the violent way they were killed.

CHAKRABARTI: Similarly, Daranda Hinkey, who you heard from just a few minutes ago, she really disagrees with the idea that the community will benefit from the lithium mining at Thacker Pass and that the Paiute-Shoshone Tribal Council made a mistake, she says, in signing that community agreement with Lithium Americas.

We talked about the Community Benefit Center and other things. Daranda feels, as a whole, none of it was enough.

HINKEY: My personal opinion, I felt like it was like a really like cheap way of telling us, here's a little bit of something. And it didn't really feel that was like a legitimate payoff or something to like actually benefit the community.

This company is going to be enormous and financially really well off. They're going to be billionaires. And the tribe that's closest and going to have the, is most affected by it, gets like this chump amount of change, but also this chump amount of benefit.

CHAKRABARTI: Scott, tell me what your response is to those very diverse points of view within indigenous communities in Nevada themselves, and what do you think it indicates?

LAKE: I think it indicates that we have issues that probably should be resolved if we're not going to repeat the mistakes of the past. Here in Nevada, we've been stuck in this boom-and-bust cycle of resource extraction since Nevada became state. And even before that. I think we have a decision to make whether we're going to do this differently.

We're going to do this in a way that reflects the knowledge we've gained over time. Or if we're going to keep doing business as usual, means a lot of these negative things that you just heard about in those clips. Essentially wealth being extracted and exported. Local communities are left to bear the brunt of the impacts.

It does not necessarily have to be this way. I think one thing that we've been trying to get across is that we can both extract lithium and protect the environment. We can both extract lithium and protect local communities. We can respect the values of the first inhabitants of this area.

And at the same time, recover the resources we need.

CHAKRABARTI: Yeah.

LAKE: It's just that we need to take a few extra steps to get there. And I think that, you know, like I said before. I think going about it this way ultimately slows us down. Because I would not, I don't want to spend all of my time fighting with the projects. And if we could just resolve these issues at the outset, I think it would be a much more efficient process and ultimately a much less costly process.

This program aired on March 11, 2024.