Advertisement

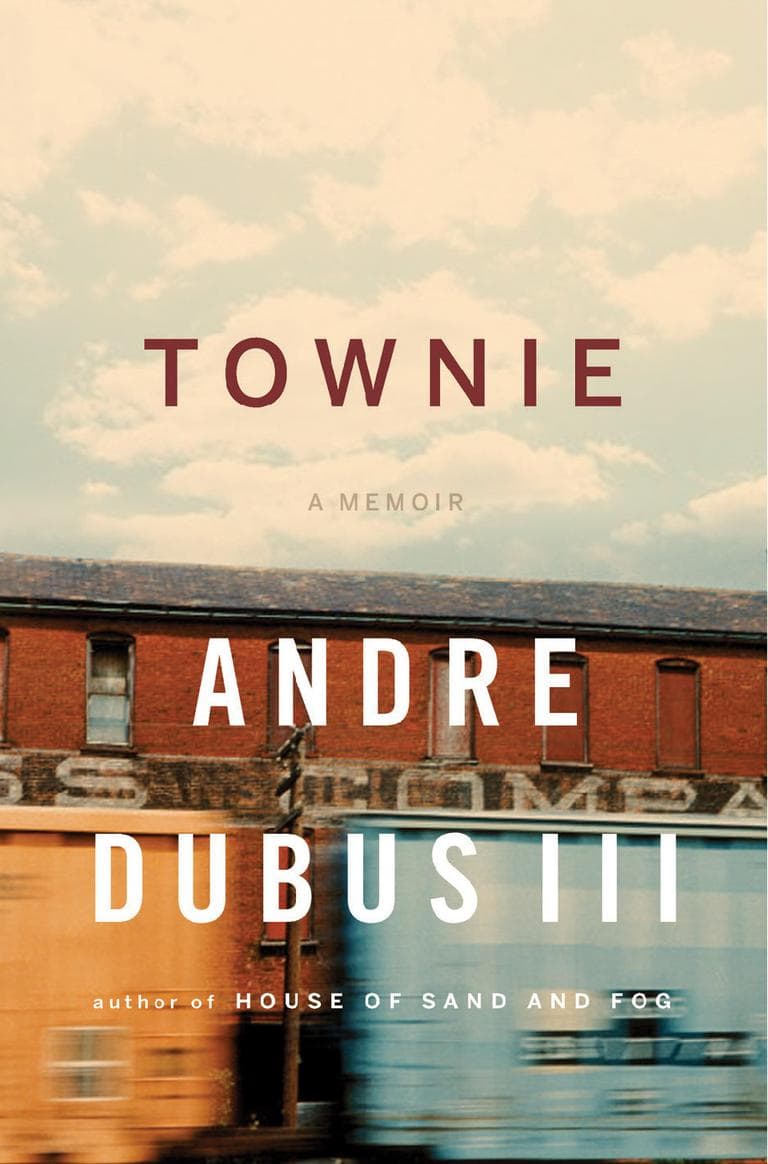

Andre Dubus: From 'Townie' To Boxer To Writer

Andre Dubus III was a child when his family left Iowa for the mill towns of the Merrimack Valley, in 1966. That's when things began to fall apart.

"The house was full of a lot of fighting and yelling, and a lot of tears over dead soldiers in Vietnam, and Martin Luther King was killed, and Robert Kennedy was killed, and my family broke up — it's really a year that I associate with good men getting shot in the head and my father leaving," Dubus said in a Radio Boston interview.

They grew up poor, his mother struggling to make ends meet. The family moved from place to place, always in search of cheaper rent.

Dubus rarely saw his father. He turned out to be the kid who skipped school, took drugs and ran from bullies.

"I was the kind of kid who was a target, because I was small, I wore glasses, I was a bright kid — I used words like 'actually' and 'not necessarily,'" he said.

A young man home from the Army would routinely beat up Dubus' 13-year-old brother. He pleaded with the man to stop hurting his brother, but the man just threatened him in return.

"I just stood there paralyzed with fear," Dubus said. "That was the last straw."

"I actually looked at my 14-year-old face, and I actually told my face, 'I don't care if you get killed, you're never gonna not fight back again.' And that very day I began to exercise — within a year-and-a-half I transformed my body, and then I began to fight and fight regularly."

He became a boxer. The fighter resembled nothing of the writer, who would emerge years later.

Advertisement

Dubus was dating a writer when he rediscovered literature. One night, instead of heading to the ring, "I found myself brewing tea and sitting down to write a scene instead," Dubus said. "I still do not know how that came to be. I had no intention to do that, I just did it."

He didn't want to write. He just felt like he needed to.

Since then, Dubus' novels and short stories have received wide acclaim. His 2000 novel "House of Sand and Fog" was a finalist for the National Book Award.

It wasn't until he wrote "Townie," a new memoir, that Dubus came to understand his late father's struggles.

"I truly believe that people do the best they know how to do," Dubus said. "I don't think it's usually the best we can do, because most of us can do better, but I'm convinced my father in his own way, given his own demons and his own upbringing, did the best he knew how to do with us."

Guest:

- Andre Dubus III, author, "Townie"

More:

Book Excerpt: "The Townie" (PDF)

By Andre Dubus III

The Switch

I WAS riding in the back of Peggy’s Subaru. Pop was driving. We were pulling away from Kappy’s liquor store with one of his buddies I didn’t know well. He sat in the passenger side and had a beard as wild-looking as Fidel Castro’s, and he kept talking about Romania and collective farming. It was a warm, gray afternoon. On both sides of Main Street the dirty snow banks had melted into slush, its runoff sluicing into the drains, some of them clogged with damp leaves, empty cans or cigarette packs, damp sections of newspaper.

Pop elbowed his friend. “My boy’s a Golden Glove boxer.” “What’re you, a middleweight?”

“Yeah, no.”

“No? You’re not a middleweight?” “I am, but not what he said.”

Pop’s eyes caught mine in the rearview. He was waiting for me to continue, and I could see that whatever I’d say next would be all right, that he was just curious, that’s all; this was the collateral gift of him having been a father who’d always lived somewhere else, one who had never been part of any decisions we made or did not make about our lives; he’d always been absent, and it made the next thing easy to say. “The Gloves were last week. I didn’t go.”

"How come?"

"I don't know..." "What?"

I could’ve told him about the beating I’d taken in the ring. I could’ve told him about the headache that wouldn’t go away, or how I’d begun to see my skull as a container for my brains, one that had been designed to protect them so why was I encouraging people to punch it as hard as they could? Weren’t there other things I could learn to do?

“I think I should be doing something more creative.”

I did not say artistic, though I was thinking that. I did not say I’d started to write a short story for the first time and that each night after work I looked forward to that tea and to that table, to my pencil I would sharpen with the U-knife from my carpentry apron, the lined notebook I was slowly filling with words and sentences and paragraphs. I did not tell him that just doing this left me feeling pleasantly empty of some- thing after, something I normally would have brought into the ring or the weight room.

Pop said, “Interesting.” And he downshifted and drove the three of us along Main Street. We were heading off to a Bradford College faculty party somewhere, a dinner with grown men and women like the man beside Pop, people who had Ph.D.’s and taught and wrote, people who danced and painted and sculpted. Pop’s friend was talking about Romania again, and I was looking out the window at this place that had become my hometown, the street Rosie P. had lived on, her sweet smile and naked brown legs. Columbia Park and the house my mother had worked so hard to keep us in, the longest we’d ever been anywhere, the tree house in the back made from stolen lumber, the attic turret I’d exiled myself to, the sidewalk in front where Tommy J. had punched my brother in the face and called my mother a whore. There were the worn apartment stairs beside Pleasant Spa where early in the morning kids from the avenues still waited for the bus and passed joints and drank Pepsis or Cokes. And Cleary’s side street, his loving drunk mother.

Pop’s friend was talking about Miles Davis now and we were driving through Monument Square, a new restaurant where I had nearly beaten a boy to death. My father was driving and he could keep driving. Then we were on the Basilere Bridge over the Merrimack River, and as I watched the dark water flow east past the concrete floodwall and Captain Chris’s Restaurant and the boxboard factory on the opposite bank, there was this recognition of movement, that like the currents below I was being pulled from what I had known to what I did not yet know, that for now I was suspended between two worlds.

IN MAY I finished writing a short story. It was set in Louisiana and was about a young man caring for his ailing grandmother. Every afternoon the grandmother’s elderly friend brings fresh blackberries she’s picked and the grandson takes them and puts them with the rest, but he’s getting tired of baking blackberry cobbler and blackberry pie and blackberry bread and muffins, and he’s about to throw them all out when one afternoon, as he’s getting ready to serve the women coffee, he overhears the friend crying and telling his grandmother how unhappy she is because she lives with her son and daughter-in-law and grandchildren in their small house and she doesn’t want to be a burden, doesn’t want to be any trouble, and that’s why she leaves the house every day with her empty coffee can to pick blackberries. But now the season’s over, she weeps, and she doesn’t know what to do with herself anymore. In the final scene, the grandson decides to keep all the blackberries she’s picked, and he bakes for days.

It was an overwritten, sentimental story, something I wouldn’t know till months had passed after finishing it. But as I wrote that last line my heart was thumping against my sternum and my mouth was dry and I felt pulled along by something larger than I was, something not in me but in this story that had come out of me.

It was a Saturday afternoon, warm enough I didn’t need a jacket. I grabbed my workout clothes and left my apartment. The inside of my car smelled like sawdust and the leather of my carpentry apron on the backseat. For a few miles the day was too bright and real and I blinked at it from the dream I'd cast myself in with the two old ladies and the young man and all those blackberries. Then I was on the back roads heading west. Instead of playing the radio, hunting for that one good song, I drove along in silence. On both sides of the road were woods, but today, for the first time, I saw them as individual trees, each one different from the one beside it or in front of it or behind it. One was as bent with age and weight as an old man, another as thin and straight as a young girl, one pine, the other maple or elm or oak, and the sun seemed to shine on each sprouting leaf, on each needle, on the black telephone lines sweeping from pole to pole, on the veined creosote at their bases, on each pebble at the side of the road, each broken piece of asphalt, each diamond of broken glass from a smashed bottle or cracked mirror or discarded compact from a woman I would never meet. And I felt more like me than I ever had, as if the years I’d lived so far had formed layers of skin and muscle over myself that others saw as me when the real one had been underneath all along, and writing—even writing badly—had peeled away those layers, and I knew then that if I wanted to stay this awake and alive, if I wanted to stay me, I would have to keep writing.

This segment aired on February 28, 2011.