Advertisement

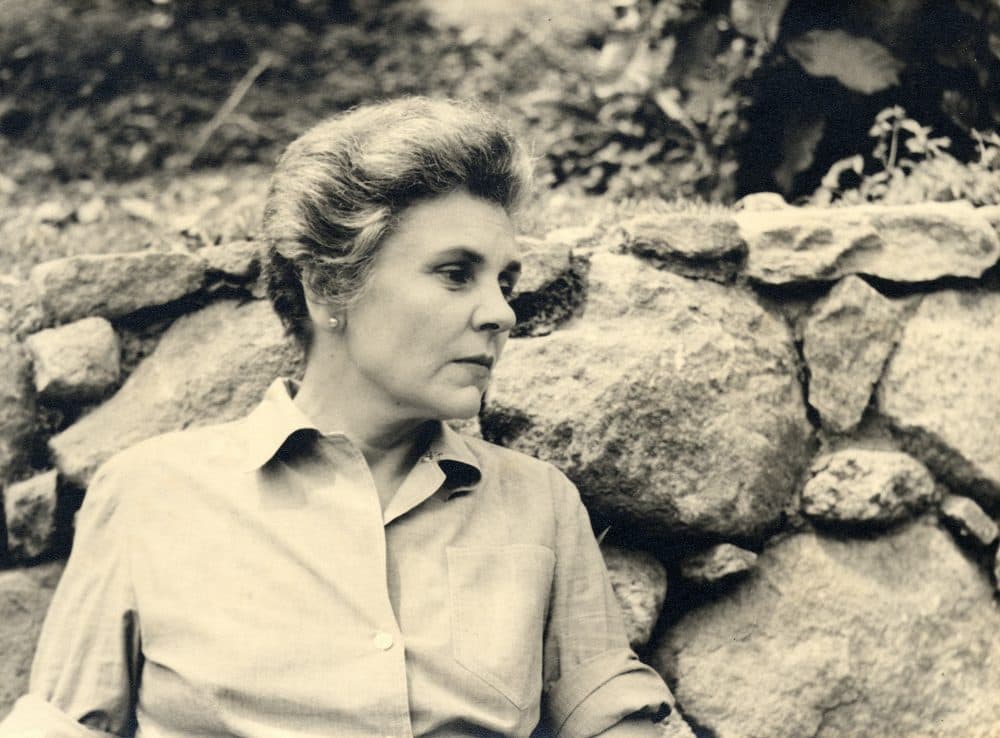

The Life And Poetic Legacy Of Elizabeth Bishop

Resume

One of the legends of 20th century poetry wrote sparingly — but her work still resonates.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master;

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

That's the beginning of the poem "One Art" by Elizabeth Bishop. It is one of her best-known poems, published near the end of her life. It speaks of an "art of losing" that Bishop had to practice during her own life.

Bishop, who was born in Worcester, lost her father as a baby. Her mother was institutionalized throughout her childhood. And the rest of her life was marked by tumultuous love affairs, deaths of friends and her battle with alcoholism.

Megan Marshall will be reading at the Brookline Booksmith on Wednesday, Feb. 22nd, at 7 p.m. and Harvard's Houghton Library on Feb. 27 at 6 p.m.

Guest

Megan Marshall, author of "Elizabeth Bishop: A Miracle for Breakfast." Professor of narrative nonfiction at Emerson College. Winner of the Pulitzer Prize in biography for "Margaret Fuller: A New American Life."

Interview Highlights

On Bishop's contributions to the literary world

"She came to the stage of poetry at a time where it was mostly male dominated, but she managed to sneak in a kind of new poetry that was based in the old.

She was attracted to verse form. She wrote sestinas, villanelles, but she also incorporated a kind of modernism of everyday speech and of very acute observation — so she was writing in old forms but she was writing new poetry."

On why Bishop's poems have staying power

"She said that to write poetry, is thinking with one's feelings. I think that's a wonderful description of the kind of poetry she wrote.

Her contemporaries, Robert Lowell, Sylvia Plath and [Anne] Sexton, were writing very naked confessional poetry that was gripping at the time, but it loses a bit today when we're not any longer in the time in which they were writing and confessing. Her poems are personal but they're also universal."

On being a student of Bishop's

"I was a dropout from Bennington College and hanging around in Harvard Square and I began taking courses at Harvard ... I was lucky to get into a workshop class with Robert Lowell. And after those classes, I transferred to Harvard and continued to really study poetry. That became my thing.

I got into Elizabeth Bishop's class my senior year and she was not the star that Robert Lowell was — it's hard to believe that now because her name certainly ascended beyond his. And it was a curious class ... She appeared a kind of small, older woman looking kind of shy and nervous and she began by saying, 'I don't believe poetry can be taught.' What were we supposed to think about that?

I came to really respect that honesty. Above all, this is what she was — honest in her poems. And if she wasn't outright open about her love life, her lesbianism — a word she would not have used because she was closeted — she was very honest in her opinions about what we might do as poets, what could be accomplished.

And she had arrived at poetry almost as a life raft I think, a refuge and a place of expression through a very difficult life. I don't think she -- that's part of what she felt couldn't be taught. And also I think sometimes people who have an innate talent for something aren't really the best teachers of it. But the message really was you had to be rigorous on your own, you had to teach yourself, you had to write, inspire yourself and live the life that was going to be the basis of poems."

On what made her want to write about Bishop

"... When I began to write this book, I was very aware that this experience as a student at Harvard with these eminent poets had kind of set me up for the life of a biographer. I was close to them but maybe only as a close as a biographer might ever come to a subject.

I wanted to write about Bishop. I had thought I'd write a short book, kind of a personal appreciation. She published only 100 poems in her lifetime. But then when I began looking into it, I learned that her late life lover, Alice Methfessel, who was almost 30 years younger, had held onto some key correspondences and they came to light after Alice's death in 2009.

The love affair between Alice and Elizabeth, nobody really knew what that consisted of until the letters between them surfaced. There were letters that Elizabeth had written in her late 30s when she was in psychoanalysis to her analyst and that's how we know about the abuse from the uncle. This is something she had never told anyone except very close friends.

We also know about her early experiences of falling in love with girls and women. Previous biographers that had sort of guessed they would say, well she was working out her sexuality, we don't really know. But here, we learned that she was reading Havelock Ellis when she was a young teenager learning about what then was called sexual inversion ... She was not made to feel ashamed by what she was reading."

This article was originally published on February 20, 2017.

This segment aired on February 20, 2017.