Advertisement

Commentary

My father survived starvation as a child. He never forgot what it meant to be hungry

My father knew hunger intimately. In one of my earliest memories of him, we sat on opposite ends of a big brown leather couch in our Sudbury home, and I watched him ingest a fish. He tore into the fermented herring, cold from the Sudbury Farms grocery deli counter, with bare hands. He stuck his face into the belly, ripping it apart. He chewed to its core, spitting bones to the side of a plate on the coffee table in front of him. He wasted nothing.

Seven-year-old me watched, horrified. How had he come to eat like this? My friends’ fathers used utensils, put napkins in their laps. They didn’t hunch over their food and come back up only when it was gone. My dad turned to me and smiled an exaggerated smile, masticating with an open mouth like a bear, oil glistening on his gray mustache.

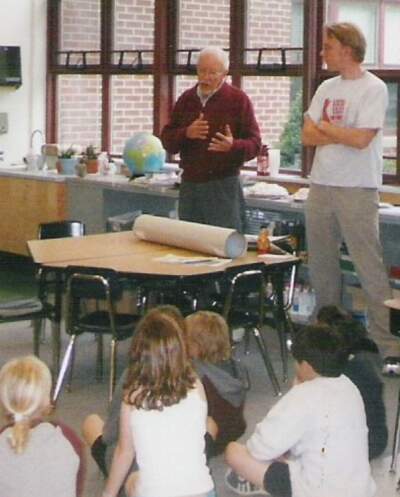

In my early 20s, I conducted 50 hours of interviews with my father about his experience of World War II. He was 10 when the Nazis invaded Belarus in 1941. His mother, a high-ranking member of the Communist Party and an atheist, was murdered on the second day of the invasion. My father was orphaned.

Suddenly food—how to get it, how to function without it—became the through line in his survival story.

I remember my father’s precarious relationship to food as international conflicts rage, knowing civilians will suffer. The fighting that began a year ago in Sudan’s capital Khartoum has led to millions enduring acute hunger. Former Sudanese prime minister Abdalla Hamdok said that 25 million people, more than half the country’s population, are at threat of starvation. People in parts of Mali, Somalia, Burkina Faso and Haiti face similar scenarios.

News of food scarcity from Gaza is unrelenting. According to a report from the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), an initiative for improving food security and nutrition analysis, famine is imminent in northern Gaza by May, and the remainder of Gaza by June. The IPC defines famine as “an extreme deprivation of food” where “starvation, death, destitution, and extremely critical levels of acute malnutrition are or will likely be evident.” As of April 17, at least 28 children in northern Gaza have died from malnutrition and dehydration.

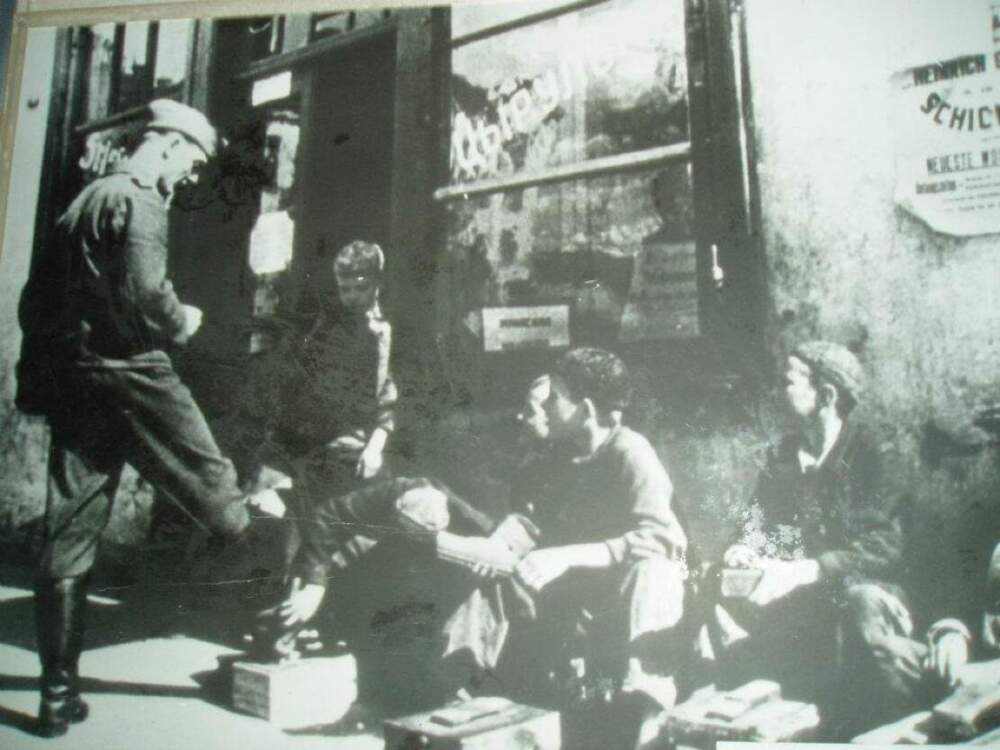

During World War II, my father became what he needed to be to eat: first a beggar, then a thief. At the start of the Nazi occupation, he went door-to-door to the homes still standing, but as the population’s food supply dwindled, he stole from the field kitchens the Nazis established on the ground.

“Sometimes I got away with it,” he told me. “In the beginning I could move quickly and avoid [punishment], but when I no longer had the energy to move out of the way, I got a boot from a soldier.”

Alex de Waal in the Guardian warns that:

As the body starves, its immune system begins to fail. The malnourished fall prey to waterborne infections and causes diarrhea, which causes devastating dehydration. Other communal diseases also ravage communities. The most common cause of death in a famine is disease, not starvation as such.

Perhaps my father, who ended up living in the burned-out buildings of Minsk and collaborating with other orphans to find food didn’t understand this aspect of starvation when he told me: “Some kids gave up. They just sat there and died.”

He recounted a three-month stint in the winter of 1942 when he, 11 at the time, slipped in and out of consciousness. He only survived because a neighbor established a sick house in an abandoned store and brought him there, to die or for his body to work it out. In research I conducted after his death in 2002, I found he had likely suffered from typhus fever, the disease thought to have killed Anne Frank in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. Typhus, spread through contact with infected body lice, which ran rampant Minsk’s ghettos, can cause meningoencephalitis, coma and delirium.

My father survived typhus and the war, but the food scarcity he fought as a child informed the rest of his life. He named keeping his 11 children “fed” as his highest priority as a father.

In Gaza, the threat of famine is man-made. Aid officials have documented and described restricted shipments of food, slow and arbitrary inspections of trucks and a lack of access to limited resources. The nongovernmental organization Oxfam reports that hundreds of thousands of people in northern Gaza are trying to survive on an average of 245 calories a day.

I used to wonder why, before meals, my father prayed aloud, “We thank you Lord for the food we receive, and we thank you for all other things.” Food was foremost, everything else came after. During our interviews, when I questioned my father about his parenting, he countered as though I had no clue what difficult was: “Did you ever go hungry?”

“You can’t do anything without food,” he said.

The IPC warns that if Israel invades the southern city of Rafah, the expanded conflict could “drive over 1 million people—half of Gaza’s population—into catastrophic hunger.”

You can’t do anything without food. It’s not something humans ought to know. May roads open, may food come in. May the weapon of starvation die. Not the people.