Advertisement

'It Was Like A War Zone': Busing In Boston

ResumeFirst of two parts. Here's Part 2. Note: Report contains some offensive language.

BOSTON — With Boston public school students back in class, we recall a very different start to school 40 years ago. Then, classes began a week late to give students, schools and the police extra time to prepare for the first day of court-ordered desegregation.

Earlier that summer of 1974, federal District Court Judge W. Arthur Garrity ruled that the Boston School Committee had deliberately segregated the city’s schools, creating one system for blacks and another for whites — separate, unequal and unconstitutional.

The remedy to achieve racial balance and desegregate schools was busing. Some 18,000 black and white students were ordered to take buses to schools outside of their neighborhoods.

'The Words. The Spit.'

Here's how The Boston Globe headlined that first day of court-ordered busing: "Boston Schools Desegregated, Opening Day Generally Peaceful". The headline was reassuring, if not exactly accurate. It was only Phase 1 of the federal desegregation plan. Just 59 of 201 schools were desegregated that day, and it was far from peaceful at South Boston High School.

Southie was ground zero for anti-busing rage. Hundreds of white demonstrators — children and their parents — pelted a caravan of 20 school buses carrying students from nearly all-black Roxbury to all-white South Boston. The police wore riot gear.

"I remember riding the buses to protect the kids going up to South Boston High School," Jean McGuire, who was a bus safety monitor, recalled recently. "And the bricks through the window. Signs hanging out those buildings, 'Nigger Go Home.' Pictures of monkeys. The words. The spit. People just felt it was all right to attack children."

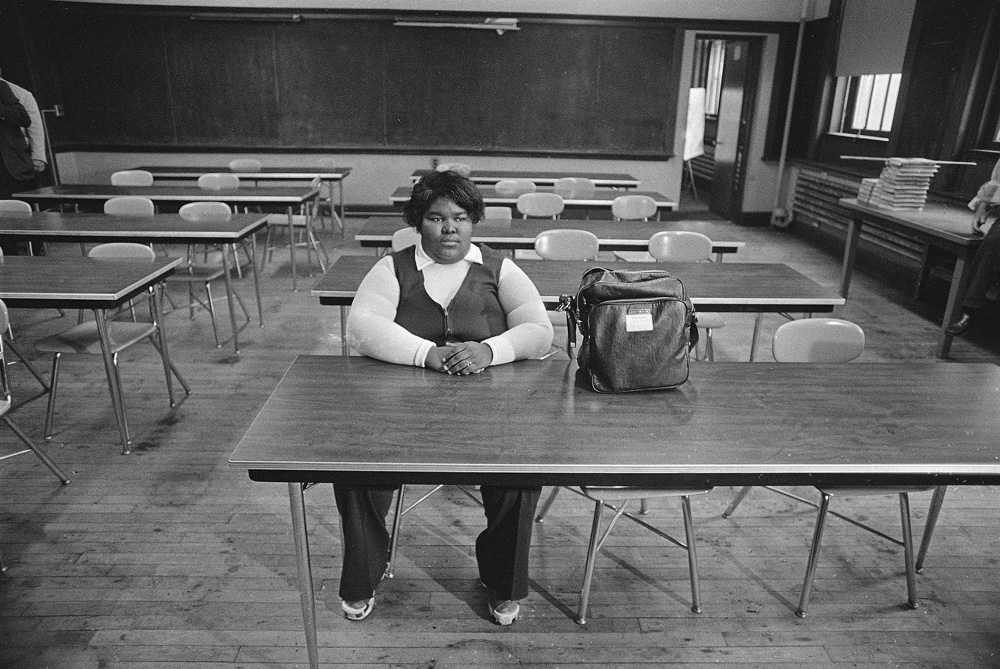

One of those children was Regina Williams.

"I had no idea what to expect [with] this busing thing," Williams said. "I didn't know anything about South Boston. I didn't know anything about, you know, they didn't like us. I didn't know anything that was in store for us. But when we got there, it was like a war zone.

"I came back and I told my mom, and I'll never forget, I said, 'Ma, I am not going back to that school unless I have a gun.' At 14 years old. I am not going back to that school."

And Williams didn't. And neither did many other students assigned to the five schools affected by busing in Roxbury and South Boston. Just 20 white students attended Roxbury High that first day, and no whites showed up at South Boston High.

On the second day of school, South Boston High headmaster William Reid reported that things hadn't improved much at the five schools.

"The attendance today was 321 blacks, 50 whites and 11 of other minorities, out of an estimated enrollment of 4,000," Reid said to reporters then.

'I Don’t Want Nothing To Do With It'

South Boston parents who were most opposed to busing formed the group Restore Our Alienated Rights. They wanted to keep their children in neighborhood schools, and issued a call for whites to boycott classes. The group made up lyrics to the tune "My Way," sung by Frank Sinatra. "Tonight, let us unite, and do it ROAR's way," the song said in part.

The song may have been hokey, but the white student boycott was devastatingly effective.

At the time a reporter for WGBH-TV interviewed a student named Mike. Here it is:

Mike: "Why am I not going to school? I'm boycotting."

Reporter: "How come?"

Mike: "How come? Why do you think? The cops are up there, they're locking up the schools from the outside. Plus there's busing. I don't want nothing to do with it."

Reporter: "How long are you going to stay out?"

Mike: "All year."

Reporter: "If you stay out all year, what are you going to do next year? You're going to lose a whole year."

Mike: "Then I guess I'll have to lose it. That's all there is to it."

Reporter: "Do you think this is going to stop it?"

Mike: "I think if we get a total boycott it'll stop it."

The year busing began, there were 86,000 students enrolled in Boston public schools, more than half of them white. Today there are 54,000 students, and less than 14 percent are white.

Many parents who could afford it moved to the suburbs or sent their children to private or parochial schools, despite a plea by the city's Catholic leader, Cardinal Humberto Medeiros, not to disrupt desegregation efforts.

Among those who took his child out of public school was the president of the Boston School Committee, John Kerrigan, an opponent of busing. He said the schools were unsafe.

'Boston Has Gotten Out Of Control'

From the start of busing, police at South Boston High outnumbered students. Yet the violence continued. Then-Mayor Kevin White, making a rare TV appeal, declared a curfew and banned crowds near the school, but said there was only so much he could do to protect students and enforce the federal mandate.

"The court has ruled that busing is the law in Boston," White said then, "and this city is under a federal court order. The Boston police cannot implement the law alone."

Law enforcement tactics toughened, and what had started out as an anti-busing problem soon included anti-police sentiment. Many of the police officers were Irish from Southie.

"I had never seen that kind of anger in my life. It was so ugly," said patrolman Francis Mickey Roache (South Boston High Class of 1954), who was on duty at the school that first day of desegregation, when protesters turned on him.

"These are women, and people who were probably my mother's age, and they were just screaming, 'Mickey, you gotta quit, you gotta quit!' They picked me out because they knew me. I was a South Boston boy, I grew up in Southie," he remembered. "And I said, 'I'm just standing there.' I said, 'I'm assigned to this. I have five children. I love my profession. I don't wish you any harm but I'm here to make sure that nobody gets hurt.' And in the police department I wasn't too popular."

A decade later Roache would become Boston police commissioner. But as the 1974 school year wore on, there was no peace.

By October The Boston Globe wrote: "What we prayed wouldn't happen has happened. The city of Boston has gotten out of control."

A group of whites in South Boston brutally beat a Haitian resident of Roxbury who had driven into their neighborhood. A month later some black students stabbed a white student at South Boston High. The school was shut down for a month.

Then-Gov. Francis Sargent put the National Guard on alert. State police were called in and would remain on duty on the streets of South Boston for the next three years.

But President Gerald Ford refused to mobilize U.S. marshals, saying it was up to federal court judges to enforce the desegregation order.

"The court decision in that case, in my judgment, was not the best solution to quality education in Boston," Ford said then. "I have consistently opposed forced busing to achieve racial balance as a solution to quality education."

The disagreement among city, state and federal officials took its toll on the very students the leaders were supposed to be helping. These white high schoolers were documented in the civil rights series "Eyes on the Prize":

"Right now I'm just so confused, between Mayor White and the rest of them, I really just feel like dropping out of society. Really, that's the way I feel."

"The seniors really feel bad. You have your school ring and there won't be no prom, there's nothing going on. I mean it affects everybody, but the seniors really hurt."

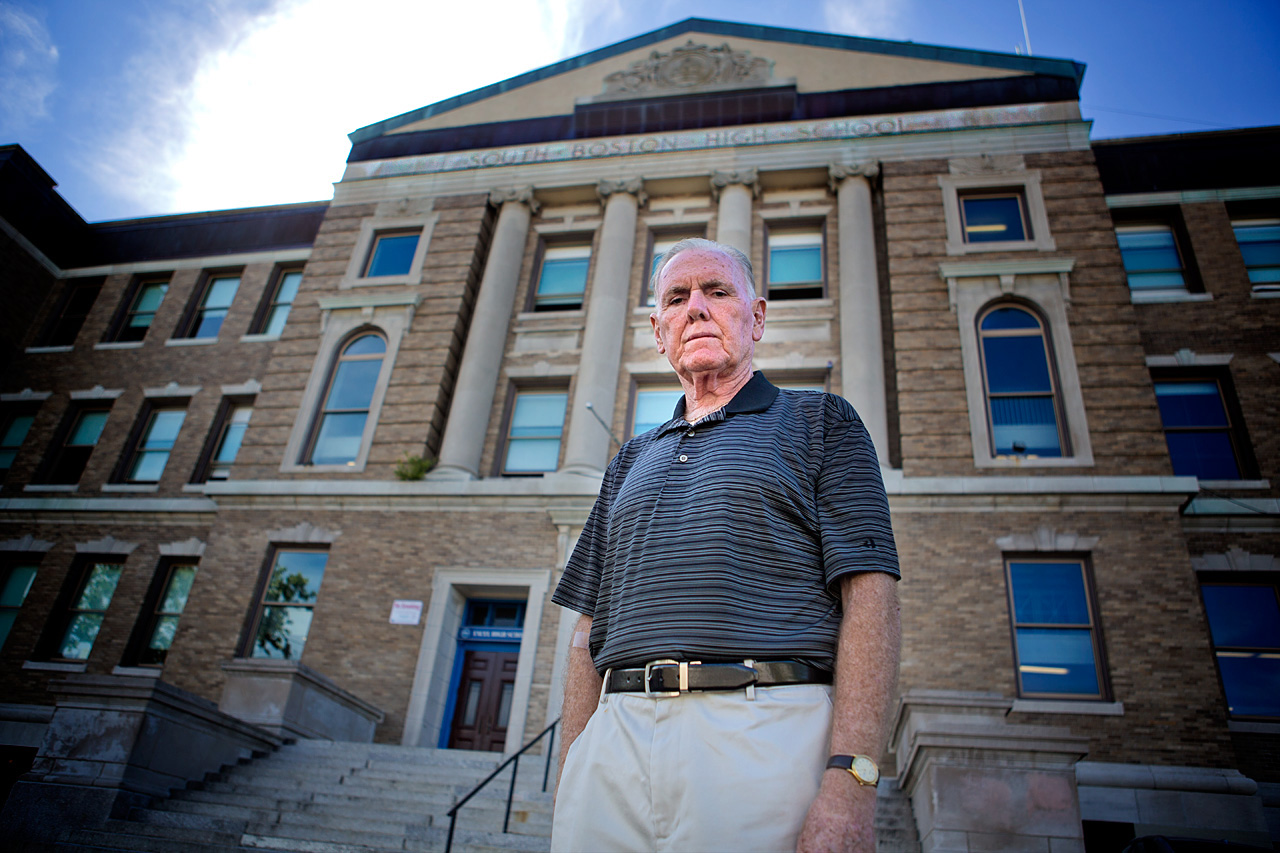

Four decades have passed since these students voiced their frustrations and fears for the future, but Ray Flynn — South Boston's state representative during the busing crisis, later mayor of the city and now 75 and retired — says they still have not been heard.

"That story of those people most affected, most negatively impacted, that affected their education and their quality of life, has never, ever been really told in a significant way," Flynn said on the steps of South Boston High recently. "I hate to die and this story never be told."

Later this month, WBUR is organizing an on-air busing roundtable. We want to hear from former BPS students who were bused to school in 1974. If that's you, and you're interested in participating in our conversation, please send a note to reporter Asma Khalid.

This segment aired on September 4, 2014.