Advertisement

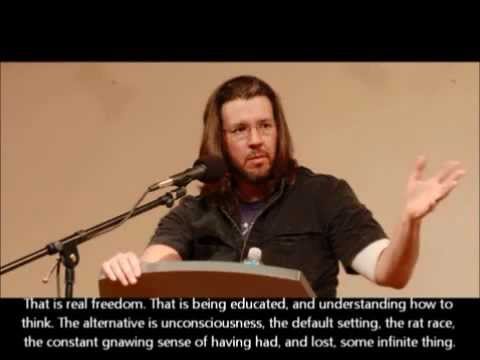

David Foster Wallace, 'Infinite Jest' And Lessons In Empathy

Like most David Foster Wallace fans of a certain age, I only came to know his work after his death. The first DFW piece I read was the Kenyon commencement speech, which was making the rounds as I was preparing to graduate from college in 2011. Like most sheltered people graduating from college, I was utterly terrified of entering the real world. I attempted to postpone this entry by spending a year in a master’s program for journalism.

But New York City, where I did my journalism year, does not care how smart you are, or what your credentials are. And being extremely well-read in critical theory has almost no bearing on the essential work of journalism. I was not adjusting well to life outside the warm walls of Georgian architecture and without the validation of teachers and friends. As Wallace warned in the commencement speech, “Worship your intellect, being seen as smart — you will end up feeling stupid.”

Desperate to feel good about myself, I reached for “Infinite Jest.” I wanted to feel smart again, to conquer this behemoth of a book. There are multiple story lines and many characters, told in non-linear chronology through multiple points of view. On its surface, “Infinite Jest” is a caper about a Quebecois separatist trying to obtain a film so entertaining, anyone who views it loses the will to live. But really, it’s interrogating the deep, abiding, terrifying loneliness and sadness that Americans feel and try to keep at bay by distracting themselves through entertainment --whether in the form of drugs or the consumption of media or things. I had read some of the same theorists and philosophers Wallace read, I was pretty well-versed in post-modernism, I had written about David Lynch in college. Surely I could read this book.

Reading "Infinite Jest" was a humbling experience. It took me several months and I don’t remember much of the specifics. The thing I do remember is that reading this novel changed my life, which I know is a cliché, but please, bear with me.

In an interview with WBUR’s Christopher Lydon in 1996, Wallace described why he came to Boston: “[I] came to Boston because in the late ‘80s, I was pretty confused about writing and not sure what I wanted to do.”

Wallace came to Boston in 1989 to get his Ph.D in philosophy at Harvard, after getting an MFA at the University of Arizona. His biographer, D.T. Max, said he came a few months before the school year started, in 1989, to party and have fun with his college friend. They lived in an apartment in Somerville, near Inman Square. Later that year, Wallace was hospitalized at McLean’s — the psychiatric hospital in Belmont, prescribed an anti-depressant and sent to a halfway house in Brighton for his alcohol addiction. “That’s where he has a moment that is key for his own fiction, for his own life, where he realizes that he’s got to try to live differently,” D.T. Max told me. “He’s got to change his whole idea of who he is and what his relation to other people should be. In other words, instead of being a show off and a guy who lives for his own pleasure, and to impress other people, he has to think about things like meaning and faith.”

Advertisement

It would appear that Wallace found the guidance he needed to interrogate and live with his own addictions and sadness — and what would become the thematic core of "Infinite Jest" — through the people he met at AA meetings. “I’d never really seen how a lot of people live. My chance to see that was here in Boston,” Wallace said in the Lydon interview. “I didn’t really understand emotionally that there were people around who didn’t have enough to eat, who weren’t warm enough, who didn’t have a place to live, whose parents beat the hell out of them regularly.”

One of the characters, Geoffrey Day, is an intellectual who teaches at a community college and “manned the helm of a Scholarly Quarterly,” a “red-wine-and-Quaaludes man” who comes to the halfway house, called Ennet House in the book. He’s in charge of recovering addicts and Ennet House staffer Don Gately, who wants to pummel him. Day does not believe in the AA clichés: “One day at a time. Easy does it. First things first. Courage is fear that has said its prayers. Ask for help. Thy will not mine be done. It works if you work it. Grow or go. Keep coming back.’”

Wallace goes on:“If Day ever gets lucky and breaks down, finally, and comes to the front office at night to scream that he can’t take it anymore and clutch at Gately’s pantcuff and blubber and beg for help at any cost, Gately’ll get to tell Day the thing is that the clichéd directives are a lot more deep and hard to actually do. To try and live by instead of just say.”

Bill Lattanzi, who sometimes leads literary tours of "Infinite Jest’s" locations in Boston, says the experience of learning from people who weren’t as formally educated as he was, must have been humbling for Wallace. “I think he was shocked and amazed to discover that these people were really smart and they knew a lot about life and they had a lot to teach him,” Lattanzi told me. “He had learned all this intellectual stuff, in the metaphorical, Harvard side of his life, but in Brighton he learned how to live.”

In an interview with Larry McCaffery, Wallace said the work of fiction is to make people feel “less alone inside.”

Reading “Infinite Jest” made me feel that way. Seeing Boston through the eyes of drug addicts and meeting them as fully realized characters — the minutiae of their life stories, their internal monologues laid out honestly — gave me a different way to interact with the world.

He had learned all this intellectual stuff, in the metaphorical, Harvard side of his life, but in Brighton he learned how to live.

Bill Lattanzi

It dawned on me slowly, after months of ruminating on Wallace and finally entering the “real world” myself, that I would be less miserable if I stopped looking inside myself, and started looking out; if I really attempted to be truly curious about other people’s experiences.

Here’s how Wallace describes the difference between “Identifying” and “Comparing” – which is basically looking at how you are different:

“The residents’ House counselors suggest that they sit right up at the front of the hall where they can see the pores in the speaker’s nose and try to Identify instead of Compare. Again, Identify means empathize. Identifying, unless you’ve got a stake in Comparing, isn’t very hard to do, here. Because if you sit up front and listen hard, all the speakers’ stories of decline and fall and surrender are basically alike, and like your own.”

And this idea isn’t just about making a personal lifestyle change. In the interview with Lydon, Wallace goes off on what he says is a tangent, but is clearly integrally linked to this idea of valuing other people’s lives as you value your own:

“What makes me sad is that I would like my generation to realize that it would be way better for us, like inside, in our stomachs, to be willing to pay higher taxes to be able to shelter and feed poor people,” Wallace said, “So that we would be the sort of culture that doesn’t let people die. And that instead we are all so worried about an extra four percent off our monthly paycheck that we get all exercised about it.”

It’s this political implication of empathy that I hold close and think about often, especially as a journalist. There are days when I do find it extremely difficult to have any empathy. The deaths of children under the supervision of the Department of Children and Families, the T's meltdown over the winter and the revelation of its fiscal and infrastructure problems, and rampant opioid addiction have been the main news since I moved to Boston. I encounter people who have suffered, who have done terrible things because the circumstances of their lives are hard, whose failures make me impatient. I want to scream at them, “Take some responsibility for yourself!”

I have to really check myself and say, No. There is a structural context for this, in which people’s individual choices are severely circumscribed. There are people who don’t have access to good schools, whose access to legitimate, well-paid employment is limited, agencies that are so poorly funded or badly managed, that it’s difficult for the low-level employees to do their jobs, but they probably still come into work every day. And so, in encountering these people, in learning about their declines and falls and quiet triumphs, I recognize it isn’t about blaming a person, but holding systems accountable. And that means doing some soul-searching and holding myself accountable.