Advertisement

'Writing The Poems Back Into The Life': Biography Delves Into Elizabeth Bishop's Devotion To Poetry

"The eminences that you are in the presence of do teach you,” says acclaimed biographer Megan Marshall. “Even if not directly how to write a poem, there are messages about life that are significant and how you conduct yourself, what’s important, what matters."

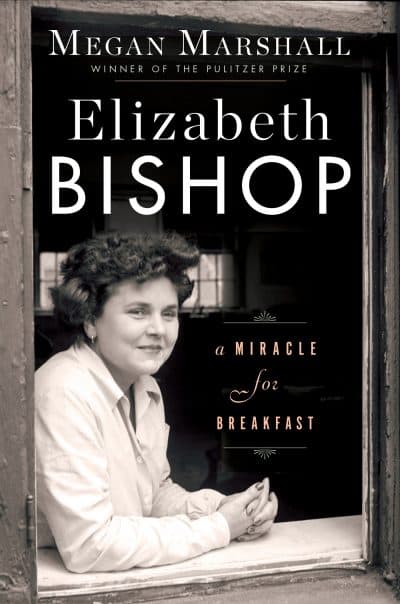

In her new book, "Elizabeth Bishop: A Miracle for Breakfast," Marshall uncovers the story of a woman whose devotion to her art gave rise to 101 beloved poems and inspired many readers and writers — the biographer among them.

Marshall now has admiring writing students of her own (I was one of them), but her latest project traces her beginnings as a student-poet, including a semester in one of Bishop's poetry workshops at Harvard in 1976. Marshall met “Miss Bishop” in April 1975 when the poet visited a writing workshop taught by Robert Lowell.

In the book, she recalls the “small older woman with short, stiff white hair, clad in an elegant light-wool suit and carrying a thin black binder” who sat down across from her: “...In a low, hoarse smoker’s voice, smoothed out with the buttery r’s of New England’s upper crust,” Bishop read “Poem,” which describes a tiny oil painting of a Nova Scotia pasture that she knew from childhood: " 'Life and the memory of it cramped, / dim, on a piece of Bristol board, / dim, but how live, how touching in detail…' "

Writing her own story into the biography is daring, especially because the relationship between Bishop and Marshall was not warm or close — a conflict between the two women haunts the narrative. In general, Bishop was not enthusiastic about discussing her work publicly, and she told her students she was unsure whether writing could be taught.

Yet Bishop’s influence on her student is clear and powerful, not only in the trajectory of the memoir but also — maybe even more so — in the curious, careful way in which Marshall crafted the biography.

Marshall reaches back to scenes from Bishop’s earliest days, starting with the very first words on her life: her birth on Feb. 8, 1911 in Worcester, as recorded in a red baby book. In those pages, Marshall uncovers the tragedies of Bishop’s childhood -- her father’s death when she was 8 months old, shuttling between relatives’ homes in Massachusetts and Nova Scotia, her mother’s institutonalization when Elizabeth was just 5 years old — and the "dislocations [that] followed, the sort that startle a child with vivid new impressions and force early memories," as Marshall puts it.

The tender attentiveness that Marshall lavishes on her subject will be familiar to fans of her previous biographies — the Pulitzer-winning "Margaret Fuller: A New American Life" (2013) and Pulitzer finalist "The Peabody Sisters: Three Women Who Ignited American Romanticism" (2005), which were praised for their absorbing narratives and emotional intimacy. “I’m trying to animate the person and give the reader the feeling that they’re going through life along with that person,” says Marshall. In the case of Bishop, that meant taking her limited but revered oeuvre and "writing the poems back into the life."

"What makes my kind of biography possible is someone who has a lot of testimony and recording of inner life to draw on. Then you can get closer to that person," says Marshall.

As Marshall knew, Bishop was not necessarily an easy person to get close to. She was very private, and she lived at a time when publicly acknowledging aspects of her life, such as her sexuality or her struggle with alcoholism, might not be met with acceptance or compassion. Fortunately, however, Marshall had access to Bishop’s rich correspondence, including some letters that previous biographers have not used that open new windows into some of the poet’s romantic relationships and childhood.

Marshall also uses the personal documents to understand the rhythms of the poet’s process and routines. She tracks — sometimes to the letter — what Bishop read and wrote as she composed her verses, and also where she sat, what music she listened to, what kind of bread she baked and coffee she drank. Marshall knows that the particulars of place, of habit and gesture, are the pulses of a life.

Close observation is at the heart of Bishop’s poems, too. In "The Moose," she takes readers on a vivid sensory journey, "From the narrow provinces / of fish and bread and tea," — her childhood home in Nova Scotia — through "the New Brunswick woods, / hairy, scratchy, splintery; / moonlight and mist / caught in them like lamb’s wool / on bushes in a pasture." By the time the titular creature appears (in the 23rd of 28 stanzas), the poem answers its own question, “Why, why do we feel / (we all feel) this sweet / sensation of joy?”

“[Bishop and Marshall] are both interested in details that add up to things,” says Lloyd Schwartz, an internationally recognized Bishop scholar and an ARTery contributor who read an early version of the book. “It’s the small detail as a kind of epiphany. It’s a rarer form of observation. It’s one of the things they have in common.”

That keen sense is not all that the two writers have in common. Though Marshall still wishes she could write “one immortal poem,” as her former teacher did (maybe more than once), she has immortalized self-educated women who have become heroes to many readers.

Yet Marshall has not lost the sense of commitment and wonder that she brought to her first poetry workshops. "We’re all apprentices in some way,” she says. We all can be taught — maybe not to write perfect poems, but at least to learn from them. The miracle that Bishop and Marshall reveal in this book is that those who approach life with a learner’s eyes will find teachers everywhere: in lines of verse, in sheaves of letters, in a chance encounter — with a master, or a moose, which “by craning backward, / ... can be seen / on the moonlit macadam.”

The book launch is at Harvard Bookstore on Feb. 7, followed by a reading at Brookline Booksmith on Feb. 22. A lecture and reading with recordings of Bishop will take place at Harvard on Feb. 27. Marshall will be in conversation with The ARTery's Lloyd Schwartz at Porter Square Books on April 20. More information on these and other local events can be found here.