Advertisement

Review

CSC Puts On An Achingly Affecting Series Of Samuel Beckett's Short Plays

If Man is born astride a grave, as Pozzo says in “Waiting for Godot,” he takes a whole lot of snapshots as he’s falling in. Memories they’re called, and the saddest are of things lost or never quite had. That’s the theme of “Beckett in Brief,” an achingly affecting bill of short plays by the famously terse and utterly merciless vaudevillian of the Void. Directed by James Seymour, the triple bill is being given a striking production by Commonwealth Shakespeare Company (at Babson College’s Sorenson Center for the Arts through May 7) that might as well be subtitled “The Will Lyman Show.”

“Words are all we have,” Beckett observed. And one could do worse than to put these precious commodities into the mouth that narrates “Frontline.” But as he proved in Commonwealth Shakespeare Company’s “King Lear” and demonstrates again here, Lyman (who is a friend) is much more as an actor than just that measured, sonorous voice. Still, who better to perform “Krapp’s Last Tape,” half of which is a voiceover?

Lyman’s solo turn as Krapp is the profoundly moving kicker of “Beckett in Brief.” On this program, it’s preceded by the rather more obscure “Rough for Radio II,” first broadcast in 1976, here given an arrestingly sinister staging by Seymour, and “The Old Tune,” which was also written for radio — not by Beckett but by his French writer chum Robert Pinget as “La Manivelle.” Beckett, in his English adaptation, turns Pinget’s old French coots into antiquated Dubliners running (well, hobbling) into each other on the street.

Spread across the wide Sorenson Center stage, “Rough for Radio II” resembles a shadow-puppet play, but with live actors. Seated at opposite ends of a long table behind a screen, lit so as to be seen in silhouette, Lyman is the Animator, Ashley Risteen his efficient if exaggeratedly sexualized Stenographer. Unseen is Fox, a prisoner from whom fragmented recollections (an interior twin, a woman named Maud) are being coaxed by means of a bullwhip wielded, at the Animator’s command, by the neither seen nor heard Dick.

Interpreted, by those who profess to understand it at all, as a metaphor for the creative process in all its dogged cruelty, “Rough for Radio II” presents the animator/artist as an obsessive taskmaster. The Stenographer, reading back to him scraps of previous sessions with their unseen human lab rat, is his more empathetic amanuensis. As for the tormented Fox, his every addled utterance subject to intense scrutiny and analysis: Might he be the wrenchingly coaxed, slowly cohering creation?

Whatever the meaning of the strange exchange, Seymour obviously gets Beckett. His production underlines the linguistic precision, the odd humor, the existential conundrums. Here, while Fox’s whimpered outbursts are understated, Risteen is a secretary both brusque and emotive, obedient yet aware of her powers. And Lyman, barking orders as his silhouetted head slowly moves toward and back from the table, his long fingers pointing or flailing upward, makes of the Animator’s dictatorial sufferings almost a ballet.

“The Old Tune” has been aptly described as Beckett Lite — but then, it’s not entirely Beckett. Rather, it’s Pinget inimitably remodeled by Beckett. Lyman and the facially expressive Ken Baltin are Gorman and Cream, no doubt inspired by septuagenarian Dubliners Beckett knew in his youth. As for Gorman and Cream, their salad days hark back to the late 19th century, a gentler era evoked in the old boys’ fond, almost musical recollections of “broughams” and “barouches.” Now, as they rest their old bones on a small step, they — and we — are subjected to the loud gunning of passing automobiles.

Cream, a widower, lives with a daughter; Gorman's wife is "still in it." Back in the day, the two were friends; here they meet by chance and stop to bemoan the passage of time while picking at each other's slipping memories. Occasionally, the melancholy "old tune" recurs, its pitch more perfect than the oldsters’ recollections.

Faced with today, the elderly pair pooh-pooh progress and fail to share a cigarette. Baltin’s easily exasperated Cream yanks about in his pockets in frustration. Lyman’s Gorman is more dazed in his dotage. Joined in their who’s-on-first dance of reminiscence and correction, both are funny and yet touching.

“Krapp’s Last Tape” is the best known of these mordant turns. Like nesting Russian dolls of regret, it depicts a solitary old man in his den, listening to a tape he recorded 30 years earlier, on which the speaker, his 39-year-old self, comments disparagingly on another tape, made some 10 or 12 years earlier when Krapp was in his callow 20s. The younger Krapps have in common that they vigorously proclaim gladness that youth and love are behind them. The present Krapp, increasingly deep in his cups and too dispirited to even finish his “last” tape, is not so sure.

For all of the plays, scenic designer James Fenton has framed the action in a proscenium of harsh fluorescent light, with sound designer Elizabeth Callas cranking up the melancholy via Vivaldi cello sonatas. For “Krapp’s Last Tape,” lighting designer Alexander Fetchko, taking his cue from Beckett, surrounds Krapp’s island of a desk in a sea of darkness that gradually encroaches on a sorrowful, intently listening Krapp who is, as Shakespeare would say, "sans everything."

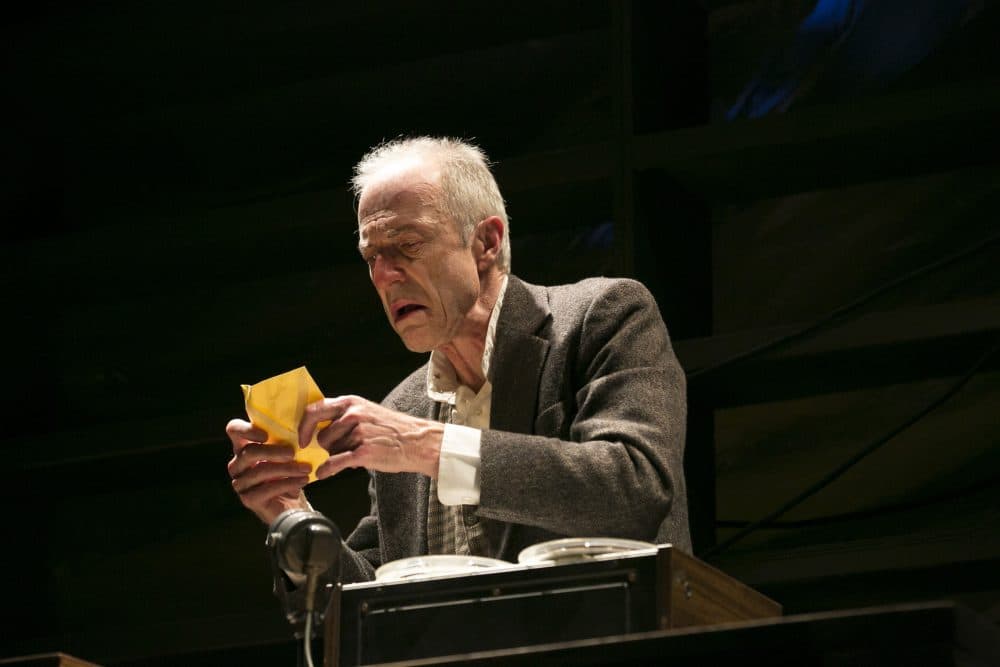

But first there is the existential clown show Beckett seldom can resist. Lyman’s Krapp enters in his “old rags” and a pointy pair of “dirty white boots,” his visage capped by a subtle riff on a red nose. Ignoring the stacked boxes of tapes, he rummages in two locked drawers of his desk for — a banana. Which he proceeds to strip and eat, ultimately — yes — slipping on the peel. He even has the audacity to repeat the action, with a few variations, before getting down to the business of manhandling his old-time tape recorder while breaking our hearts.

Lyman pulls off the vaudeville with authoritative flair. His Krapp does not so much walk as lurch — in Seymour’s staging not just to an unseen bar at the back of the stage but down to a basement into which he disappears from time to time in a jerky clamor. Alcoholically fortified, he returns carrying some dust-exuding tome: a catalogue of old tapes, a dictionary full of the exacting, exotic words for which Krapp turned his back on the “chance of happiness” conjured in a repeated recollection of making love in a gently rocking punt.

A connoisseur of language, Krapp is particularly enamored of the word “spool,” spooling it out with a wink and a chuckle. But he becomes less playful as he communes more deeply with the personal life he put aside for an art that never amounted to much. Lyman is not the crankiest or the most nostalgic Krapp I’ve ever seen. But he is the most anguished. In the end, in the encroaching dark, his face a mask of rue, this Krapp, contemplating death, looks like it.