Advertisement

At The Worcester Art Museum, New Signs Tell Visitors Which Early American Subjects Benefited From Slavery

Resume

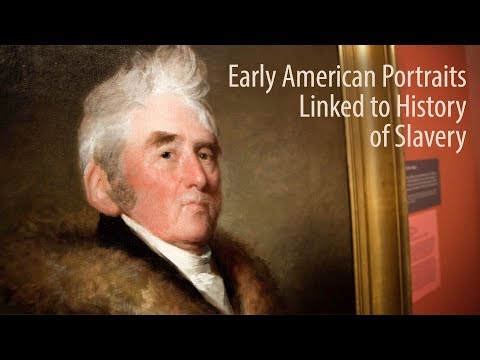

At the Worcester Art Museum's early American portrait gallery, I was recently struck by a painting of a man named Russell Sturgis. In the portrait, Sturgis wears a coat with a fur stole and what looks like luxurious taffeta. He sits on a gilded chair, with lush green velvet padding. His expression is stately and dignified, as if imbuing thoughtfulness. The painting embodies the qualities of early portraiture in colonial America: It portrays the sitter's best self and was commissioned by wealthy patrons as a family heirloom.

"It's his gaze that is somewhat upward. He's not looking directly at us, in a way," said Erin Corrales-Diaz, the museum’s assistant curator of American art. "We the viewers are sort of positioned a little bit below him in the painting."

A conventional sign next to the piece informs us that Gilbert Stuart, mostly known for painting George Washington's portrait, painted Sturgis in 1822. A new sign above that, informs us that Sturgis' relatives established a business in present-day Haiti that trafficked in flour, horses and enslaved persons.

"We tend to think of New England and Massachusetts in particular as an abolitionist state, which it was, of course, but there's this kind of flattening of the discussion of slavery and its history in the states — that the North was not at all complicit and it was a Southern enterprise," said Elizabeth Athens, the Worcester Art Museum's former curator of American Art who put up the new signs last fall. She's now at the National Gallery of Art.

After re-evaluating the permanent collection, she said she felt it almost unethical to allow the early American gallery to frame history with an uneven narrative that effaced people of color.

"It was exclusively wealthy, white people and they're presented in this very kind of valorized way," she said. "We were missing a whole swath of humanity that was part of American history. And I really wanted to correct that."

Walking through the Worcester collection reminded me of Fred Wilson's 1992 "Mining the Museum" project. Wilson looked through storage at the Maryland Historical Society and found artifacts related to slavery the museum had acquired but not displayed. He then placed those objects on view next to the conventional artifacts on display, such as slave shackles next to a gilded chair. "Mining the Museum" is considered a seminal moment, but there's been no widespread efforts to re-contextualize the many American collections across the country to reflect the excluded experiences of people of color.

LaTanya Autry, a doctoral candidate at the University of Delaware who focuses on American art and last year began the social media campaign #MuseumsAreNotNeutral, thinks museums have been resistant to including context about slavery to their collections because they'd be applying 21st-century values to works of the past. The conventional thinking that contemporary framing doesn't do the art justice is still prevalent in cultural institutions.

"Particularly with art museums, there's this idea that it's a place for beauty that when you sit there some kind of way, that social, political reality dissipates, and it's just a clean, pure experience," Autry explained in a recent interview.

Applying contemporary standards to an artwork could also mean limiting the museum's programming potential.

"It's a problem with how we teach and practice art history — that we want to carve out that space of art as a sort of autonomous realm," said Aruna D'Souza, author of "Whitewalling: Art, Race and Protest in 3 Acts."

"There can be no fiction of the autonomous realm anymore. We have to see everything we're doing as part of this vast structure that upholds a continuing oppression of Black people and people of color," D'Souza added.

Dispelling the notion of the autonomous realm of art means acknowledging that cultural institutions function within the system of inequality in the U.S. and that there has undoubtedly been inherent bias in what museums acquire and how they display it.

D'Souza thinks mid-size institutions, like the Worcester Art Museum, are in a position to lead this kind of re-framing, as opposed to larger, legacy institutions with more corporate structures. "I actually love that [the Worcester museum put up the new signs] without fanfare because I think that one of the things that is a danger for museums is too much patting themselves on the back."

Back at the quiet American gallery, the space is unchanged, but also radically different, said Athens.

"In many ways, nothing has really changed. I mean the artworks are the same and they're in the same layout. But then at the same time, everything has changed because they're kind of reframed and you see them in a different light."

This segment aired on June 7, 2018.