Advertisement

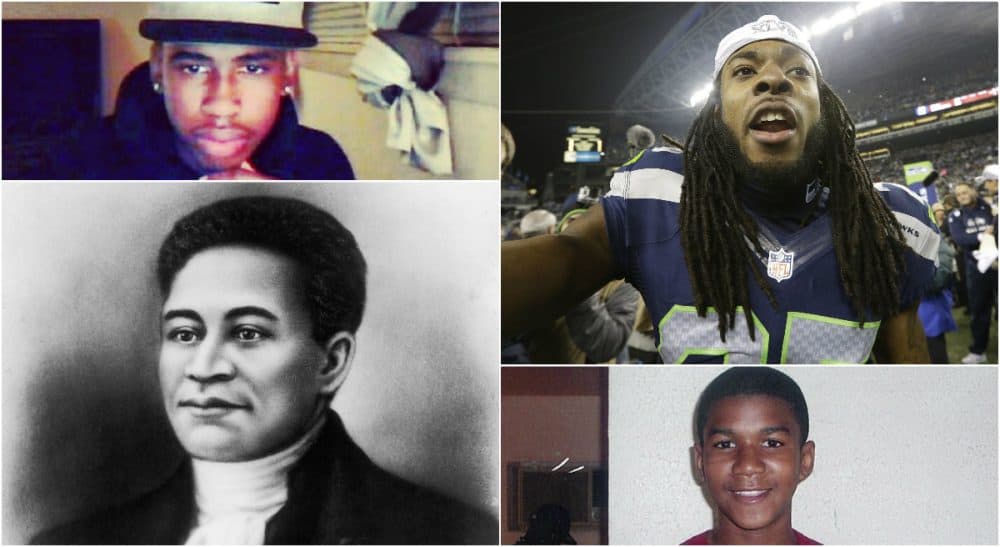

The ‘Threatening’ ‘Thug’ Through History

The word “thug” has come to define societal views of black men. Piggybacking on fears of imminent racial violence, it’s become a kind of pejorative shorthand. Most recently, the case of Michael Dunn has outraged many people over the killing of yet another unarmed young black teenager over perceptions of “thug” behavior. Taken into context with two other incidents — the death of Trayvon Martin and the acquittal of George Zimmerman, along with the January post-game NFL interview of Richard Sherman — use of the word has exploded. On one day last month, “thug” was used 625 times on television alone.

From a historical perspective, this phenomenon of using racially charged language to discuss black behavior begins much earlier.

On March 5, 1770, Crispus Attucks was killed by British soldiers during the Boston Massacre. Most Americans know this story because Attucks is one of only a handful of black individuals from the colonial period that the public can readily recall. But what few people know is that the lawyer tasked with defending the British soldiers was none other than our beloved founding father, John Adams.

It is clear that in over 250 years of history, the racially charged perceptions of black men as bearers of a physique so innately menacing that their 'looks' alone are 'enough to terrify any person' has not changed.

When presenting his case, Adams described the men killed as “a motley rabble of saucy boys, negroes and molattoes, Irish teagues and outlandish jack tarrs.” To put this in contemporary language, he was basically describing the men as nothing more than a group of “thugs.” He centered his defense of the British soldiers on the charge that Attucks struck the first blow and led the “dreadful carnage.” Adams concluded the “mad behavior” of Attucks provoked the soldiers’ response, claiming that the group was “under the command of a stout molatto fellow, whose very looks, was enough to terrify any person.”

This defense sounds eerily familiar.

So, what about Attucks’s looks seemed terrifying? Attucks, an escaped slave from Framingham, Mass., was 47-years-old when the massacre occurred. He was reportedly 6 feet 2 inches tall, with curly hair. He was described as a “molatto,” or mulatto, allegedly having an African father and a Native American mother. Adams emphasizes Attucks’ race several times within his summation. Why would this emphasis be important? Moreover, why is Attucks’s behavior alone singled out? Why, of the several men killed, is Attucks the only one we know? Furthermore, why is Attucks physical description the primary focus of the threat?

My theory: Adams is playing the race card. He concludes his statements by exploiting the racial stereotypes generally associated with rebellious slaves and attaching the soldiers’ reasonable fear directly to Attucks’s racial status.

Adams uses Attucks’s race to arouse sympathy for the terrified British soldiers and invokes what is commonly known as “Blackstone's Ratio,” the notion that “it is better that 10 guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer.” Protection of innocent whites from a terrifying black person had to be the ultimate goal, for without which collective security has no meaning for white citizens. He rests on the rationale that these soldiers were rightfully (and racially) afraid.

Advertisement

When the case concludes, six of the eight soldiers involved were acquitted after two and a half hours of jury deliberation. The remaining two soldiers were found guilty of manslaughter for firing into the crowd. But both were eventually given reduced sentences from death to the branding of their thumb in court, a proverbial slap on the wrist, if there ever was one.

It is clear that in over 250 years of history, the racially charged perceptions of black men as bearers of a physique so innately menacing that their “looks” alone are “enough to terrify any person” has not changed. The Attucks case provides an implied precedent that powerfully explains the lack of justice present when whites cite self-defense in criminal cases against black people.

In the case of Trayvon Martin, the fear of blackness as dangerous weighed heavily in the acquittal of George Zimmerman, who on his 911 call declared, “This guy’s looks like he’s up to no good...”

When will the 'innocence' John Adams speaks of ever be accorded to black men and women?

Pan-African studies professor, Shirletta Kinchen, offered a most sobering thought recently when she summed up the tragedy of Jordan Davis this way on her Facebook page: Had [Jordan] Davis been alone in the car, Michael Dunn would have walked away a free man as well.

Or on the (now defunct) justicefordunn website, an author who claims to be Dunn writes, “I blame ‘Gangsta Rap’ music and the thug culture that goes along with it for influencing violence.” Some could call it coded language, but I call it racism, which somehow makes black men responsible for their own deaths.

When will the “innocence” John Adams speaks of ever be accorded to black men and women?Indeed, past is prologue. But for black Americans, few can afford to live in the present or in the past, there is only the present past. From Oscar Grant to Trayvon Martin, to Renisha McBride, to Jonathan Ferrell, to Jordan Davis, the times, it seems, will always be a reincarnation of black suffering. As William Faulkner famously said, “The past is never dead. It's not even past.”

Related: