Advertisement

'Invisible Man': Why Ralph Ellison's Classic Novel Still Matters

Ezra Pound famously defined literature as “news that stays news.” I teach contemporary literature to college students, and we often wonder which works published in our century will withstand that mysterious test of time. In my moodier moments, I worry that very few novels (the genre I study most) will be read generations hence. My worry stems not from a sense that great novels aren’t being written anymore, for I believe they are. Rather, I’m concerned that the acceleration of the availability of news and other bits of information will make novels an extinct species. I already feel like they’re lumbering around in their late Cretaceous period.

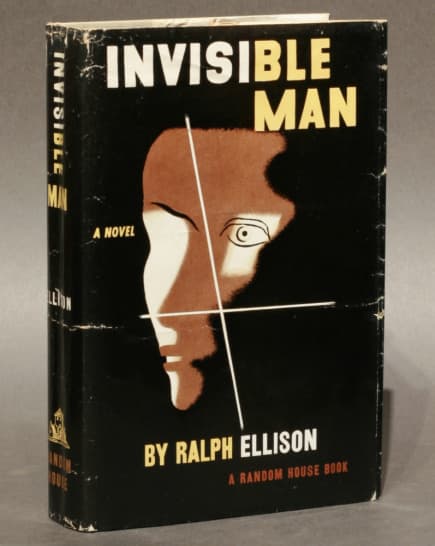

March 1, 2014 would have been Ralph Waldo Ellison’s 100th birthday, so I’d like to use this occasion to call attention to a novel that remains news more than a half-century after it was published. “Invisible Man,” published in 1952, was the first novel written by an African American to win the National Book Award. It is a magisterial work of fiction, combining allusions to great works of literature with keen insight into the complex psychology and painful social reality of being a black man in mid-20th century America. Moreover, it is engaging, mysterious, funny, sad, brainy, and honest. In short, it’s a must-read.

['Invisible Man' is] a novel of ideas. Not a single idea, but a host of them.

I’m always surprised by how few of my students have read it, or even heard of it. I’ve taught it over the years at different institutions in different contexts, and I don’t recall encountering a single student who had read it before. I also don’t recall a single student who wasn’t blown away by it. I’m teaching it right now in a survey of American literature after 1865, and there’s no need to give quizzes to make sure my students are keeping up with the reading. They’re hooked.

Well, why? What is it that makes a 50-year-old novel so engaging, especially one that is well over 500 pages long? There are a few superficial explanations. It contains sex (not much), violence (not gratuitous), a naïve narrator who takes a long time to learn life’s basic lessons, an honest and unvarnished look at racial oppression, and a cast of memorable characters. It is also a carefully crafted work that repeats its own motifs like a symphony, allowing readers to sense its unity and gauge its development without having to struggle. Its plot is engaging: the narrator is always in motion, or at least his mind is always racing, and the flow of his words carries the reader along. While all of these factors contribute to making “Invisible Man” a classic, they all support the main factor: Ellison wrote a novel of ideas. Not a single idea, but a host of them.

The American literary tradition is filled with novels of ideas, from Melville’s “Moby Dick” to Morrison’s “Beloved.” These works can’t be boiled down to a summarizing phrase or a sentence. They’re unlike news in that they need to be read carefully, reread, pondered, and discussed in order to appreciate them fully. But if the ideas behind them are substantial, if they reflect the brilliance of the author, and if they are rendered artistically, they are well worth it, especially in our era of the 24 hour news cycle that counts Justin Bieber’s latest arrest as significant.

Ellison famously exhausted himself, or perhaps terrified himself, with the publication of “Invisible Man.” Having written one of the most important, profound, substantial novels in American literary history, he lived another 40 years without producing a follow-up. He left behind a mess of a manuscript that his literary executor John Callahan eventually edited and released as “Juneteenth” after Ellison’s death. It was not well-received.

“Invisible Man” was, in many ways, a novel that would have been difficult to follow up, and Arnold Rampersad’s biography of Ellison indicates that fame undid him, to some degree. But on another level, “Invisible Man” predicts its author’s fate. It is a novel about a paralyzed man, one who does not know where to turn next after struggling against and negotiating with a world that mistreats him, clutching desperately to optimism amidst his society’s insanity. It provides a good deal to think about, but no easy answers. It begins with the word “I” and ends with “you,” forcing readers to contemplate how connected they are to the stories of others, and, as his narrator says, on a deeper level than they might realize.

I invite you to seize the occasion of Ellison’s 100th birthday to read “Invisible Man.” Or reread it. It takes a little time, but good news is worth it.

Related: