Advertisement

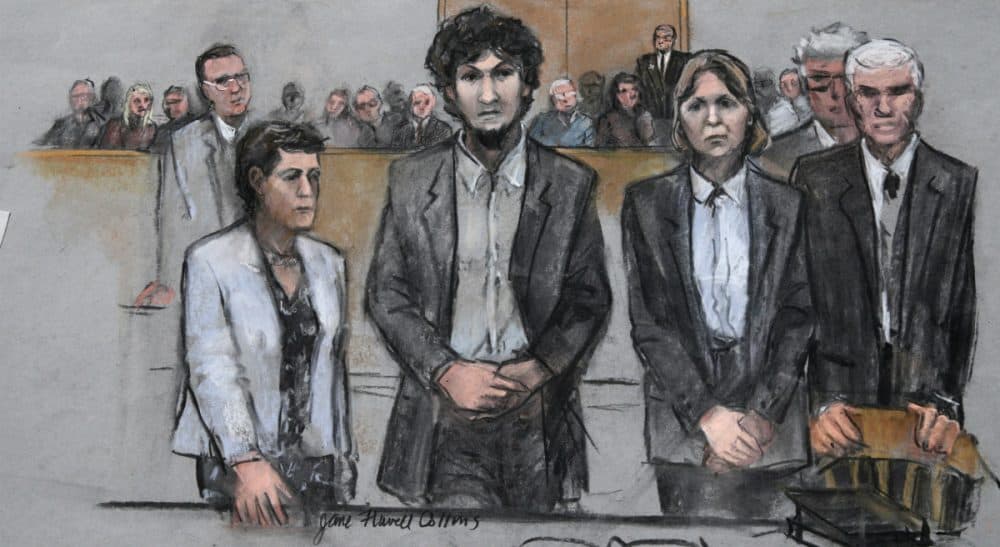

Tsarnaev And The Long Legal Road Ahead

In the aftermath of the death penalty verdict in the Boston Marathon bombing trial, we have heard frequent musings about the “endless appeals” forthcoming in the case. Yes, there are extensive post-conviction remedies in capital cases. And for good reason. As others have famously noted, there is no appeal from the grave, which means the justice system must ensure that both phases of the trial were as fair as possible and the constitutional rights of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev safeguarded before execution. The ultimate penalty warrants the ultimate process.

After Tsarnaev is formally sentenced by Judge O’Toole in the near future, the defense’s major remedies are 1.) the direct appeal, and 2.) a post-conviction filing pursuant to habeas corpus.

... there is no appeal from the grave, which means the justice system must ensure that both phases of the trial were as fair as possible...

The direct appeal is an explicit challenge to the trial itself; the defendant is limited to attacking what happened at the guilt and sentencing phases and is generally only allowed to raise errors that were adequately presented down below or, in the vernacular, preserved. For instance, one reason the defense filed so many motions to shift the trial to a city other than Boston lies in preservation and the desire to create an ample record for appellate review. The direct appeal is a vertical remedy; the appeal goes “up” to the federal appeals court that covers Massachusetts, known as the First Circuit, which is located right here in Boston. If the First Circuit affirms the death sentence, then the defendant has the right to ask the United States Supreme Court to hear the case.

After the completion of the direct appeal, Tsarnaev will have one year to file a petition under the federal habeas corpus law. Habeas corpus, which translates roughly to “you have the body,” emerged in England as a remedy to stop the Crown from detaining suspects indefinitely without justification before trial. Over time, habeas corpus morphed into not only a mechanism to challenge pretrial conditions but also a way to dispute the constitutionality of a defendant’s imprisonment after trial.

In a petition under the federal habeas statute, Tsarnaev could address a variety of issues, including those not preserved at trial, which go to the propriety of his continued custody. This petition would be filed in the court in which he was sentenced, the federal district court in Massachusetts. If his pursuit of the habeas corpus remedy is denied by the trial court, then he may appeal that decision to the First Circuit and eventually pursue further review in the Supreme Court.

At bottom, there are extensive appellate and post-conviction remedies, as there should be in a capital case. But they are not endless.

Now this is where the idea of endless appeals comes in. Federal law provides for the possibility of successive habeas corpus filings. Before filing another petition with the trial court, however, essentially Tsarnaev would have to first convince the First Circuit that there is newly discovered evidence that could have altered the outcome or that there is a new rule of constitutional law recognized by the Supreme Court that has been made retroactive to his case.

Let me be clear: these are just the basic remedies, and others will surely come into play. Federal law permits assorted post-trial motions as well as the chance to request the judiciary to prevent the actual execution, known as a “stay,” if and when the execution date nears. There is also the opportunity to ask the president for a reduced sentence (or even a pardon) through the executive power to grant clemency.

At bottom, there are extensive appellate and post-conviction remedies, as there should be in a capital case. But they are not endless.