Advertisement

Commentary

How Much Risk Is Football Worth?

Three years ago, I went to visit Dr. Ann McKee at her lab north of Boston. At the time, McKee, a neuropathologist, was examining the brains of former football players to compile the most detailed study to date on the relationship between football and brain injury.

This week, she and her team at Boston University School of Medicine published their long-awaited results in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

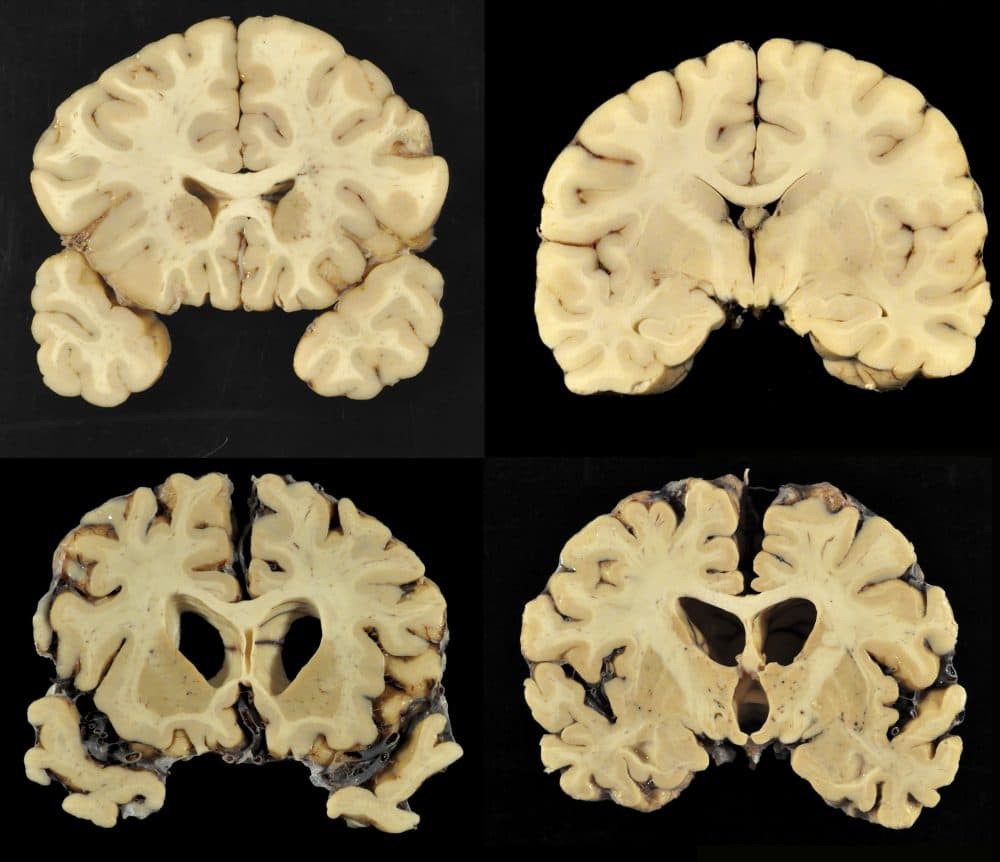

Of the 202 brains they studied, 177 showed signs of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, the degenerative disease that led to the mental decline of former stars such as Junior Seau and Mike Webster. Of the brains from NFL players, 110 out of 111 showed signs of CTE.

None of this comes as any surprise. The NFL has known for decades that football can lead to brain damage. Documents submitted by the league’s own actuaries, in response to a class action suit by former players, put the figure at 30 percent.

Football doesn’t have a concussion problem, or even a violence problem. It has a physics and physiology problem.

McKee is an intrepid researcher and a genuinely well-intentioned person. But the most striking aspect of my visit — more disturbing, in some ways, than watching her slice into the brain of a deceased female rugby player — was the fact that she was also a huge NFL fan. Her desk, covered with hundreds of slides of brain slices, also featured a bobblehead doll of Aaron Rodgers, the star quarterback of her Green Bay Packers.

When I asked McKee how she justifies watching the game, knowing its dangers so intimately, she responded: “I don’t know. I don’t know where I am. I think it’s a really important question. I have, like, these two faces. Right now they’re pretty separate.”

I know the feeling. For most of my life, I was a devout fan of the game, its grace and brutal drama. I stopped watching a few years ago, reluctantly, after seeing my mother struggle with a cognitive ailment.

Because I later wrote a book called "Against Football," NFL fans often peg me as a football hater.

Advertisement

But my book is really about the industry that has monetized the game, and the ways in which fans like me underwrite the spectacle of football, while refusing to face its darker aspects.

I have no idea whether Dr. McKee has made the connection between her fandom and the damaged brains she studies.

But I do know that the medical evidence of the risks associated with football is only going to become more obvious.

Football doesn’t have a concussion problem, or even a violence problem. It has a physics and physiology problem. The human brain wasn’t meant to absorb thousands of collisions. And that’s what happens when you play full-contact football. It’s the accretion of these hits that leads some players to develop CTE.

There is no magic helmet, or set of rules, that will make these dangers go away. They are inherent to the game. And not just at the pro and college level.

And fans should have to courage to consider whether their viewing pleasure is worth the harm that may come to those they watch.

Studies are now revealing the risks to younger players, whose brains are still developing.

Over the past three years, 17 boys have died of traumatic brain injuries from playing football. That’s a horrifying figure, one that would put the kibosh on pastimes less sacred to us than football.

But in those same three years, hundreds of thousands of boys have sustained millions of sub-concussive events that could lead to brain disease later in life.

Football is a thrilling spectacle, and a sport that holds deep meaning to players and fans alike. It will never be banned, or sued out of existence.

But players of all ages should know the risks they run. And fans should have to courage to consider whether their viewing pleasure is worth the harm that may come to those they watch.